Onward Christian Soldiers

[Part 6]

Note

This new version of Onward Christian Soldiers that I’ve compiled consists of the original contents published by Noontide Press in 1982 plus the “missing” text that, for reasons explained below, was in the Swedish version published in 1942.

I’ve also included some supplementary texts here giving the history of the missing parts of Day’s book. Also book reviews by Revilo Oliver and Amazon readers (see Part 1).

KATANA

Contents

Maps of Northern Europe & the Baltic States

THE REST OF DONALD DAY by Paul Knutson — 1984

EDITORIAL NOTE by Liberty Bell

The Resurrection of Donald Day — A review by Revilo P. Oliver. The Liberty Bell — January 1983

TWO KINDS OF COURAGE by Revilo P. Oliver. The Liberty Bell — October 1986

AMAZON REVIEWS

__________________

ONWARD CHRISTIAN SOLDIERS

Chapter

Introduction

Permit Me To Introduce Myself * (all new)

1 Why I did not go Home *………………………………. 1

2 The United States *………………………………………. 7

3 Latvia ………………………………………………………… 21

4 Meet the Bolsheviks *………………………………….. 41

5 Alliance with the Bear *……………………………….. 53

6 Poland ……………………………………………………….. 63

7 Trips ………………………………………………………….. 85

8 The Downfall of Democracy * ………………………. 93

9 Jews …………………………………………………………… 101

10 Russia *………………………………………………………. 115

11 Lithuania * ………………………………………………….. 131

12 Danzig ……………………………………………………….. 145

13 Estonia ……………………………………………………….. 151

14 Sweden ………………………………………………………. 159

15 Norway ………………………………………………………. 169

16 Finland ………………………………………………………. 183

17 England *……………………………………………………. 197

18 Europe *…………………………………………………….. 201

19 Epilogue *…………………………………………………… 204

Index of Names ………………………………………………….. 205

* Contains new material (dark blue text) missing from original Noontide edition.

MAP

of Northern Europe 1920s (click to enlarge in new window)

MAP

of Baltic States 1920s (click to enlarge in new window)

LIBERTY BELL PUBLICATIONS

June 1984

THE REST OF

DONALD DAY

by

Paul Knutson

Donald Day, who had been for many years the foreign correspondent of the Chicago Tribune in northern Europe, wrote a record of his observations, Onward, Christian Soldiers, in 1942. His English text was first published as a book in 1982. It was printed by William Morrison and appeared under the imprint of the Noontide Press of Torrance, California, As Professor Oliver pointed out in his review of that book in Liberty Bell for January, 1983, the text had been copied, with some omissions and minor changes, from an anonymously issued mimeographed transcription of a defective carbon copy of the author’s manuscript, which had been brought to the United States in someway, despite the vigilance of Franklin Roosevelt’s surreptitious thought-police.

That was not the first publication of Day’s book. A Swedish translation, Framat Krististridsman, was published by Europa Edition in Stockholm in 1944. (That paper cover, printed in red, green, and black, is reproduced in black-and-white on the following page.)

Copies of this book still survive in Sweden and are even found in some public libraries. There may still be a copy in the Library of Congress, where, however, it was catalogued and buried among the very numerous books of a different Donald Day, a very prolific writer who midwifed the autobiography of Will Rogers and produced book after book on such various subjects as American humorists, the folk-lore of the Southwest, the tourist-attractions of Texas, and probably anything for which he saw a market, including a mendacious screed entitled Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Own Story. By a supreme irony, the Library concealed Framat Kristi stridsman in its catalogue by placing it between the other Day’s Evolution of Love and his propaganda piece for the unspeakably vile monster whose millions of victims included one of the last honest journalists.

The Swedish translation contains some long and important passages that do not appear in the book published in California and are not found in the mimeographed copy. By translating these back into English, I can restore Donald Day’s meaning, but, of course, I cannot hope to reproduce exactly the words and style of his original manuscript. I can also restore from the Swedish the deficiencies of the mimeographed transcript.

It seems impossible to determine now whether the parts of Day’s work that are preserved only in the Swedish were deleted by him to shorten his text when he sent a typewritten copy to the United States or were added by him before he turned his manuscript over to the Swedish translator at about the same time. At all events, the Swedish now alone provides us with some significant parts of bay‘s book and many Americans will want to have Day’s Work complete and entire.

For the convenience of the reader, I have, by arrangement with the publisher of Liberty Bell, included corrections of the printed English text where it departs, through negligence or misunderstanding, from the mimeographed text from which it was copied. I have passed over obvious typographical errors in the printed book, and omitted small and relatively unimportant corrections. For example, near the end of p. 44 of the printed book, the sentence should read, “All reported that the officials of the Cheka, later known as the GPU and NKVD, were Jews.”

Day did not use footnotes, so the reader will understand what all the footnotes [indicated by the symbol *] on the following pages are my own explanations of the text.

The supplements below are arranged in the order of pages of the printed book, as shown by the note in the small type that precedes each section, The three sources are discriminated typographically thus; Italics show what is copied from the printed text to give continuity.

Ordinary Roman type is used for what is in the mimeographed copy but was omitted from the printed version. This, of course, is precisely what Day wrote in English.

What I have translated back from the Swedish appears in this style of type. These passages, as I have said, convey Day’s meaning without necessarily restoring exactly the words he used in his English original, from which the Swedish version was made.

*****

Editorial Note

Liberty Bell

With the foregoing supplements, we have at last as accurate a text of Donald Day’s Onward, Christian Soldiers as we are likely to have, barring the remote possibility that the manuscript Day gave to his Swedish translator may yet be discovered.

The Swedish translation is pedestrian, as indeed is Day’s English style, but a comparison of the Swedish with the extant parts of the English assures me of the translator’s general competence. In one passage, which we have only in the Swedish, in which Day reports his refusal to become a well-paid and dignified member of our Diplomatic Service with a “little Morgenthau” as an “adviser” to tell him what to do, the translator was evidently confused by the irony of some English phrase such as “executive for a Jew” and reversed Day’s obvious meaning;, this was corrected in the foregoing text.

The mimeographed version is evidently a transcription from Day’s carbon copy, with only such errors as only the most expert typists can entirely avoid. There is, however, one very odd error in the mimeographed version corresponding to our printed page 4 above; it reads “the Great Rocky mountains of the border of Tennessee and North Carolina.” That is geographically absurd, of course, and the Swedish (stora Rijkiga Bergen) shows that Day wrote “Great Smoky mountains,” as we have, printed above. It is probably only a coincidence that the Swedish word for “Smoky” could have suggested, to a person who knew no Swedish, the error made by the typist in California who copied Day’s carbon copy.

When Day relies on his recollection of what he was told years before, his memory is sometimes faulty, and we have naturally made no changes in what he wrote. He makes an obvious error on our page 4, where he says that the Cherokees were driven from their lands and moved to Indian Territory “toward the end of the last century.” Actually, the expulsion of the Cherokee Nation by an American army took place in 1838. The Cherokees, by the way, were the most nearly civilized of all the Indian tribes in the territory that is now the United States and Canada, and it is true that their expulsion from the lands that had been guaranteed to them by treaty inflicted great hardships on them: they lost most of their property, including their negro slaves, and large numbers of them perished as they were quite brutally herded from the Appalachians almost half way across the continent to what is now the southern border of Arkansas.

Ethnologists who have made intensive studies of the Indians of North America (e.g., Peter Farb) regard Sequoyah (Sequoia) as perhaps “the greatest intellect the Indians produced.” He was the son of a Cherokee woman by an unidentified white trader, and, growing up with the mother’s people, regarded himself as a Cherokee. He, however, was an exception to what Day says about half-breeds. Day may have been confused about the date of the expulsion because a few of the Cherokees succeeded in hiding from the perquisition in the wilds of the Great Smokies and were eventually given the small reservation they now occupy east of Bryson City in the toe of North Carolina. There was some agitation about them “near the end of the last century.”

The circumstances in which Day’s carbon copy was smuggled into the United States remain obscure. When the mimeographed transcription was made and first issued, it contained a prefatory page on which an anonymous writer said,

“It is my understanding that this book was published in; 1942, and then merely made an appearance at the book-sellers, when all copies were immediately withdrawn and destroyed without a single copy escaping the book-burners, I was also told that Mr. Day died shortly after this incident.”

The page was presumably withdrawn when its author learned that Day was still alive at that time and an exile in Helsinki, since the Jews who rule the United States would not permit him to return to his native land.

It is curious that the man who made the transcription, which did effectively preserve Day’s work for the future, and who was evidently a resident of California, had heard a somewhat less plausible version of the rumor that was current in Washington in 1943. (See the review by Professor Oliver in Liberty Bell, January 1983, p. 27). It is quite possible that the source of both rumors was an effort by the apparatus of the great War Criminal in the White House to prevent the publication of the Swedish translation, which, as Day tells us in the last item in our supplements, was delayed in the press for two years by a “paper shortage” and it is noteworthy that the paper for it was finally obtained in Finland, not Sweden,* Until the book was finally published in 1944, the enemies of mankind could have imagined that their pressures on Sweden had effectively prevented Day’s exposure of one phase of their activity from ever appearing in print.

[* Day’s book was published by Europa Edition in Stockholm, which, however, had to have the printing done by Mercators Tryckeri in Helsinki. Although copies of the Swedish book have been preserved, Day’s work would not now be generally known — and would be supposed lost by Americans who heard of it — if the anonymous gentleman in California had not issued his mimeographed transcription.]

_______________________

KATANA — The Liberty Bell article continues with a list of text to be added or amended to the Noontide edition. All these changes (indicated by the dark blue text) have been entered in this expanded version of Onward Christian Soldiers.

Word Totals for the Additional Text

Introduction – –

Permit Me To Introduce Myself – 5,738 (all new)

Chapter 1 – 23

Chapter 2 – 307

Chapter 3 – –

Chapter 4 – 653

Chapter 5 – 1,225

Chapter 6 – –

Chapter 7 – –

Chapter 8 – 408

Chapter 9 – –

Chapter 10 – 907

Chapter 11 – 6

Chapter 12 – –

Chapter 13 – –

Chapter 14 – –

Chapter 15 – –

Chapter 16 – –

Chapter 17 – 2,167

Chapter 18 – 1,179

Chapter 19 – 89

Total words in original = 85,311

Total additional words = 12,702

_______________

Total words in expanded version = 98,013

ONWARD

CHRISTIAN

SOLDIERS

1920-1942: Propaganda, Censorship

and One Man’s Struggle to Herald the Truth

Suppressed reports of a 20-year Chicago Tribune

correspondent in eastern Europe from 1921

Donald Day

With an introduction by Walter Trohan,

former chief of the Tribune’s Washington bureau

THE NOONTIDE PRESS

Chapter 5

Alliance with the Bear

Nobody but the members of the German community organization in the Baltic States knows how hard they worked to persuade the German Baits to abandon their homes and properties in the Baltic countries and to return to Germany and there accept recompense.* There was much intermarriage between the Baits, Latvians and Russians. In some families only one member repatriated. In others only one or two remained.

There were divorces and marriages and many, very many, broken hearts. Some of the older people who repatriated died of homesickness.

One charming feature about the people of Riga was the way they cared for their dead. The cemeteries were all beautifully situated and were tended with love. On that great Lutheran Holiday, the Totenfest, everyone seemed to visit the cemeteries to pay a call upon relatives and friends loved and lost.

_________________

[* Day begins this chapter abruptly with the events that followed the “Non-Aggression Pact” that Hitler concluded with Stalin in August 1939 in an effort to avert the Second World War. The three Baltic states (Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania) had to be conceded to the Jews’ Soviet Empire as part of the price for that treaty, but Germany insisted that the Germans residing in those states be permitted to return to Germany, where they would be compensated for the property they had to abandon. Many German families had been established in those regions for generations, and a sentimental attachment to their ancestral homes and often ties they had formed with non-German families made them understandably reluctant to leave, and Day begins his chapter with the efforts made to persuade them to save their lives. The more fat-headed, their minds stuffed with Jewish swill about “social justice” and the idealism of the gentle-souled Communists, elected to remain. The Baltic countries were occupied in 1940, and the Jews led in their hordes of savage beasts, many of them Mongoloid, for one of the glorious butcheries that warm the hearts of all “Liberal intellectuals” with secret joy, as they see in the extermination of the more intelligent and honorable members of a nation the realization of what they really mean by “spreading democracy.” Historians will long debate the wisdom of the “Non-Aggression Pact,” which gained for Germany only a short respite from attack by the military serfs of international Jewry, which had declared war on Germany in 1933.]

[Image] Riga on the coast of Latvia.

Very many people refused to leave just because they could not bear the thought of leaving these graves untended. This attitude cannot be considered entirely morbid, for sorrow has been given to us to cleanse the soul. We all have or will experience it.

The repatriated came from all sections of the population.

Some were government officials. Others held posts in the army and navy. Many had inherited business enterprises which had been in their families for generations. The repatriates felt themselves bound to the Baltic States by ties stretching back into the centuries.

[Image] A recent photo of Riga. The capital of Latvia and a Baltic Sea port. Situated on the Baltic Sea coast on the mouth of the River Daugava, Riga is the largest city in the Baltic states.

Riga was a city very largely built by German Balts. To the visitors its architecture was just as German as Danzig and Koenigsberg. Among its citizens could be found rivalry, discontent and even hatred, but they all loved Riga. So did the foreigners who lived there, myself included. The city was not too large. I often declared I never wanted to work in Chicago or New York again. Those cities are so tremendous that one frequently lives two and three hours’ ride, in auto, streetcar or subway, from one’s place of business or one’s friends. You feel yourself fortunate if you can meet your friends two or three times each year. In Riga you could see them frequently. There was the friendly, cozy atmosphere of a small town and just enough privacy to allow it to resemble a city.

The opera was probably the finest in Northern Europe, not excepting Stockholm. Its ballet was actually the best in Europe and nothing outside Russia could be compared to it. There were excellent theatres. During some seasons the Latvian, German and Russian theatres would all stage the same play. It was interesting to attend all of them and compare the different performances, all of which were good. The Russian theatre would stage Soviet plays and as all the actors had an intimate knowledge of Bolshevism and Soviet Life, they would give the performance an added satire and spice which made them noteworthy. The Jewish, Polish and Estonian theatres were also there, although less widely attended.

This competition in art and music made Riga culturally one of the most entertaining and interesting cities in Europe. Take, for instance, the ballet. Now Stockholm has a very fine ballet, but there they are all Swedes and the dancers are tall, slender, beautifully formed girls who look as though they might all have been poured out of the same mold. In Riga the ballet contained Latvians, German-Baits, Russians, Jews, Poles, Estonians, Caucasians, and among the dancers were also some English girls, daughters of families who had resided for some generations in Riga. The difference in nationality intensified the rivalry, with the result that its incomparable performances made the ballet the most popular form of entertainment in the city. When it performed, the opera was sold out. Riga’s extraordinarily high artistic life and its cultivation must be credited to the Latvians.

It has been a source of constant amazement to the occupation troops.

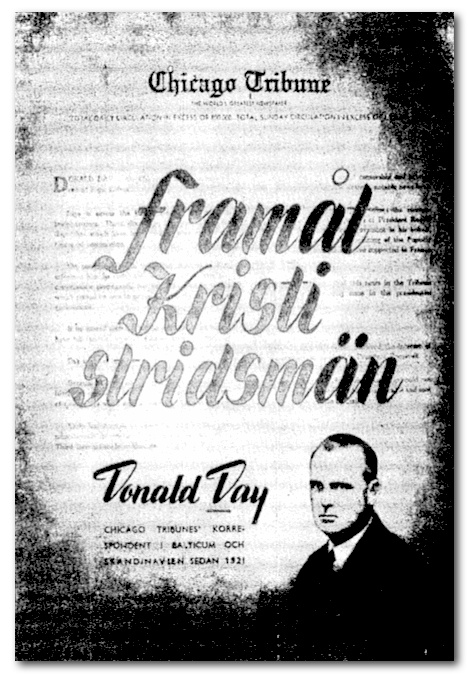

[Image] Feodor Ivanovich Chaliapin (1873 – April 12, 1938) was a Russian opera singer. The possessor of a large, deep and expressive bass voice, he enjoyed an important international career at major opera houses and is often credited with establishing the tradition of naturalistic acting in his chosen art form.

Germany was already acquainted with Riga’s musical ability and genius. When Chaliapin was engaged to perform in three Russian operas in Berlin, the choir of the Latvian opera was invited to come there and sing. At first performance, the choir received more applause than Chaliapin did himself. The ego of the artist was mortified. He demanded the conductor should alter the remaining performances so as to minimize the part of the choir. The conductor refused and Chaliapin, enraged, cancelled his engagement. The choir returned to Riga in triumph. They had “sung down” one of the greatest of living singers, an unprecedented achievement. And they had done it unintentionally.

The opera was one of the most remarkable developments and results of Latvian independence. Its past, and its performances today,* constitute a plea for the preservation of Latvian culture which has already found an echo. I arrived as an impartial American correspondent and now I must come forth as their advocate. I can truthfully report they are an essentially Nordic nation with Nordic traditions and the Nordic way of life. The Latvian blood is sound and has been enhanced rather than spoiled by the mixture of German, Swedish, Russian, French and other bloods which have flavored it in varying quantities during past centuries. Although Jewish Bolshevism with its policy of mongrelizing entire populations by the extermination of the upper classes has caused a terrible scar on the Latvian nation by liquidating the greater part of the upper class, the remainder of the population is sound and the good blood strains, which exist in all nations, remain.

[* Day is writing in 1942, when the Baltic states had been reclaimed for civilization by the German Army. His observation of the Jewish technique of destroying nations through mongrelization is extremely important, Since it is not yet feasible to stage large-scale massacres in the United States, mongrelization is promoted by agitation for “equality” and “civil rights” and by “education” to encourage miscegenation.]

I have always been an optimist concerning the future of Europe and my optimism has never faltered, as my friends can testify, even in the darkest days of Finland’s awful war for survival against the pest which rolled up like a tidal wave from the East. That wave is crashing itself to pieces against European Western culture which has helped to make the Finns the people they are.

There is not much use in seeking the blame for the debacle which overtook the Baltic States. Plenty can be found both within and without the Baltic States. Blame and advice are two things which mankind handles with the utmost generosity. it’s too bad they can’t be converted into money.

Many persons, including English propagandists and people influenced by them, have alleged to me that Germany sold the Baltic States to Moscow in return for the nonaggression pact signed on the eve of the outbreak of war. I have some facts which seem to indicate the contrary and which, at least, throw additional light on this accusation.

There are not many people in England who realize the terrific vitality of the German nation which impressed me strongly each time I visited Germany. I have some friends in London and among them were editors of The Daily Mail. I kept them informed as to developments in the Baltic and Russia and continually urged that England should ignore the insidious propaganda of the Jewish immigrants and their friends, the Bolsheviks, and make friends with Germany. I not only pointed out that Bolshevism was England’s most dangerous enemy but I put in much work and from my archives and other sources I collected all the statements.

[Page 54]

Stalin had made against the British Empire. I included excerpts from the journal of the Communist International of which I had a complete file, and other Soviet publications proving that the cardinal policy of Bolshevism was the destruction of the British Empire as being the first step on the road towards a successful world revolution.

I forwarded this material to my friends in England. I cannot forget a letter which I received from one of the editors of The Daily Mail who wrote:

“Your material and views are convincing and many of us think the same way you do. But the people in power have another opinion. They think our only chance of saving Europe and ourselves is an alliance with the bear.”

He underlined the two words “and ourselves.”

I replied that according to my information and belief the negotiations in Moscow between the British and the French missions and the Bolsheviks would collapse, for I happened to know that Germany and Russia had reached an economic agreement and I thought a political agreement might be achieved. I said Moscow wanted war and hoped that Europe would fight to exhaustion and then the Red armies with their tanks and hordes of Asiatic soldiers would descend upon Europe and the world revolution would be underway.

I told this friend, as well as other friends in England, that I could only feel sorry for England and bid them farewell as that was the last they should hear from me. These letters were written between April and August, 1939. I have not written to my friends in England since then. I was a member of the British club in Riga for many years, but I attended their weekly suppers infrequently for I disliked arguments and I was certainly heartily opposed to British policies.

The Daily Mail, I must report this to its credit, did make an attempt to prompt a better understanding between Germany and England and assigned one of their best correspondents to write articles in this direction.

But the leading Jewish advertisers in England, headed by the tremendous Lyon’s Tea Shop concern, called on The Mail and threatened the newspaper with the loss of all its Jewish advertising if it did not change its editorial policy. Confronted with the choice of threatened bankruptcy or continuing a policy which might awake England to her danger, but which most certainly would open the paper to reprisals from the government, the management of The Mail chose to obey the Jews. The last tiny chance of preventing the Jews from pursuing their policy of involving England in war was gone.

[Page 55]

In the British club, when I did appear, long discussions developed with friends. They were not heated arguments. We listened to each other’s opinions. These Englishmen had a mistaken idea of their country’s strength and of the power of their allies, France and Poland. They felt sure America would be there to help. I contended they were mistaken, that, aside from a small minority group in Washington and New York and some of the eastern states, the great bulk of America was opposed to again entering a European war, let alone sending troops to Europe. At that time I did not believe they could propagandize us into entering the war, and if they should succeed I contended it would be too late to save themselves and their empire. Now I wasn’t attempting to pose as a prophet. I only thought I knew the sentiments of the great majority of Americans and I know that England was weak, France was demoralized, Poland was a bluff, Germany was strong and that the Bolsheviks would do everything they possibly could to start a war in Europe because they confidently expected they would be the only winner to come out of the conflict.

I did make one prediction when I said I was certain that, war or no war, Europe was going to get a good dose of National Socialism, that it was going to taste like castor oil to many, but it was going to clear out a lot of poisons from Europe’s system and make things run. I have been making that prediction for the past four years and do not hesitate to repeat it today.

These talks never got anywhere. In the end the same fate over-took us all. We had to abandon our homes and lost our belongings in various quantities, but, far more important, we lost our friends. Very many are dead. Others have disappeared into Bolshevik concentration camps.

Some were evacuated to Germany, Australia and many other countries.

Here I am in Helsinki and although I have a heart-felt hope to see Riga again some day I do not expect to find many of my friends there alive.

During the spring and summer of 1939, I sent a number of cables to my newspaper reporting what I knew about the German Soviet negotiations which are supposed to have begun in November, 1938, in Stockholm. I also branded the Polish policy as insane and reported that if Poland should willfully involve herself in a war with Germany, she would last just about three weeks.

Because of my reports about Poland my picture appeared on the first page of Warsaw newspapers captioned:

“Donald Day, Chicago Tribune correspondent who is Poland’s public enemy No. 1.”

The Poles had annulled my year’s visa in March, 1939, so I was unable to visit Warsaw and report first hand about the Polish persecutions of the German minority in the Danzig corridor. I had been there many time previously and I had also covered the atrocious treatments the Poles had meted out to the Ukrainians in Galicia and the Ruthenians in the Vilna corridor.

[Page 56]

An American newspaperman always gets to the source of a story if it’s humanly possible. As the Polish reign of terror in the Danzig corridor was obviously going to be the cause of the outbreak of war, I selected the next best place to get the story first hand and went over to the Prussian-Polish frontier.

I arrived in Koenigsberg and one of the first persons I visited was an old friend, the Lithuanian Consul General Dimsa. We discussed the situation at length. He placed his car and chauffeur at my disposal and I traveled up to the Polish corridor where the German authorities permitted me to interview the German refugees from many Polish cities and towns.

The story was the same. Mass arrests and long marches along roads toward the interior of Poland. The railroads were crowded with troop movements. Those who fell by the wayside were shot. The Polish authorities seemed to have gone mad. I have been questioning people all my life and I think l know how to make deductions from the exaggerated stories told by people who have passed through harrowing personal experiences.

But even with a generous allowance, the situation was plenty bad. To me the war seemed only a question of hours.

I returned to Koenigsberg and after forwarding my stories I called up Sigrid Schultz, The Tribune correspondent in Berlin. I told her what I had seen on the frontier and that I had also seen German troops and war preparations. Not many kilometers from Koenigsburg was one of those great flat East Prussian pastures on which was mounted battalions of heavy anti-aircraft guns. I stopped the car and counted more than sixty big cannons already in position, their muzzles raised and pointing East.

The entire field was surrounded by heavy caliber machine guns at one hundred meter intervals.

I told Sigrid the British-French negotiations in Moscow had broken down, that Russia had signed an economic pact with Germany and I strongly suspected a political agreement was approaching and she should watch for this story as it might break any moment. Sigrid laughed at me.

She said, according to the existing belief among the correspondents in Berlin a pact was certain to result from the British-French-Soviet negotiations in Moscow, and she ridiculed the possibility of a Soviet-German economic agreement. Like the other correspondents in Berlin, Sigrid simply wasn’t in touch with the situation. The economic pact I told her about was announced the same night, some hours after my call to Berlin.

[Page 57]

I read about it in the Koenigsberg newspapers the next morning and immediately visited another friend, Gauleiter Erich Koch, president of East Prussia, one of those human dynamos in the Nazi movement with an extra large portion of that special genius so widely evident in Germany, the ability to create and organize.

Telling the Gauleiter of my visit to the Polish frontier and of the talks with refugees, I asked if he intended to colonize them on his land reform projects. He replied with an emphatic, No! That all those people were going to be able to return to their homes since the German government intended to reoccupy those territories which Germany had lost through the Versailles treaty and which were putsched by the Poles.

I told him of a British war plan which envisaged the British fleet entering the Baltic Sea, occupying Libau, and that the Poles were planning to strike across Lithuania from the Vilna corridor towards Libau. The Lithuanians had told me of their determination to fight. The Latvians had also turned down the Polish request for Libau as a base. I asked Koch if the forces in East Prussia would move to the assistance of Lithuania if this was necessary. He said they would.

Mentioning the economic treaty announced that morning between Moscow and Berlin, I asked if there were not a political treaty impending.

Koch thumped his fist on the desk and said there would never be a political agreement between National Socialism and Bolshevism. I asked if the status quo of the Baltic States was affected in any way by the economic agreement with Moscow and he said so far as he knew it would not be influenced and Germany would certainly not agree to the demand of the Soviet government to seize the three Baltic countries. We talked for more than an hour and when I suggested I should bring my interview to him for his approval he said:

“Mr. Day, I have known you for some years and think you are a reliable newspaperman. You may send this message without my reading it.”

Thanking him for his confidence in me, I took my leave as we intended to meet again that night at a banquet the Koenigsberg Fair Committee was tendering to the foreign exhibitors and press in the Park Hotel.

I stopped and spoke with his adjutant telling him I had obtained a very remarkable interview, that it contained lots of dynamite and before I sent it to The Tribune I should prefer to have someone go over it with me. I asked him if he would agree to read my dispatch which I intended to write immediately. He agreed. A short time later I telephoned him from the hotel saying my story was completed. He said mobilization had been declared and it was impossible for him to receive me, suggesting we meet at the banquet.

[Page 58]

Accordingly we met that evening and I asked him if he would not read and approve my cable. He said he didn’t like to take this responsibility as he did not know America well enough and suggested I should not hesitate to forward it, as the Gauleiter had confidence in me, and my previous messages had never been questioned as to their content or accuracy. But I had a very strong hunch that I should not send the message without either the Gauleiter or someone else connected with him reading it first, so, I announced my intention to hold up the message until the next day.

Responsible American newspapermen are very careful in reporting interviews. No matter what shade of political opinion an American newspaper represents, it considers it a matter of honor to publish the statements of the interviewed person as accurately as possible. It often happens in the course of a long conversation that a responsible public official will make statements which he would not like to see in print. So I have always followed the principle that if a statesman or official is considerate enough to grant me an interview, I must be considerate enough to offer to show him this interview before it is published. I make only one exception to this rule and that is when the subject quoted touches upon the interests of my own country. Gauleiter Koch was an important person in the councils of the National Socialist party. He had made statements concerning Germany’s foreign policies. Therefore I thought it best to get this interview authenticated.

We began a very enjoyable dinner. I sat at a table with Consul General Dimsa and some Koenigsberg officials. Gauleiter Koch paid me the honor of coming to my table and sitting with me for some time. We were together when one of his aides hurried into the room and told him that Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop and his staff were about to arrive in Koenigsberg on board a special flight of planes enroute to Moscow and he would spend the night in Koenigsberg.

I have never seen a more surprised group of men in my life. The Gauleiter and his staff hurried out to the airfield. I went up to my room to rewrite that dispatch which I had begun with the Gauleiter’s statement that there would never be a political agreement between National Socialist Germany and Bolshevik Russia.

My room was on the fourth floor and I noticed the doors of all the rooms had been opened. I called the maid. She knew me as I had been stopping at the hotel ever since it had been opened. I asked who were the expected guests. She said Reichminister von Ribbentrop was occupying the room next to my own and named the other guests. But I had noticed that more rooms had been prepared than there were guests and asked who was expected to fill those at the end of the corridor. She said they had been reserved for Reichsmarshall Goring. It was my turn to be surprised and I asked her how she knew that. It seems some secret servicemen attached, to the Reichsmarshall’s staff had been in the room that morning to control them and fix wires for a special telephone to Berlin.

[Page 59]

I rewrote my cable and then sent another message to London announcing the arrival of von Ribbentrop in Koenigsberg and the sensation it had caused. I then went downstairs and found the Berlin delegation had arrived. I asked one of the staff when Goring was expected and he asked me how I happened to know of this. Mentioning that “a little bird had told me”, I asked what was the purpose of his joining the party if he should arrive. This official asked me not to cable anything about the Reichsmarshall (I had not mentioned this development in my story telephoned to London) and said if he joined the party then something really tremendous was going to take place in Moscow; the Soviet five year plan was going to be coordinated with the German four year plan. I impolitely burst out laughing saying I could go to bed without worrying as the Reichsmarshall most certainly would not arrive. The official asked why I laughed and I explained I knew quite a bit about the five year plan and I thought it impossible to combine it with the German plan.

The Reichsmarshall did not arrive and very early the next morning the foreign minister and his staff continued their flight. After breakfast I wrote a note to the Gauleiter saying I was glad I had obeyed by premonition and had not forwarded the interview the previous evening. I requested him to approve the enclosed story. He returned it shortly with a warm note of thanks.

Knowing the Baltic States would be greatly interested in his statements I showed the interview to Consul General Dimsa and to the Latvian Consul Vignrebs. I then gave a copy of my story to a German colleague who was returning to Riga that evening, requesting him to give it to the official Latvian government newspaper Brive Zime with the authorization to publish it under my name.

Late in the afternoon the foreign minister and his staff returned from Moscow. After supper I looked into the wine restaurant and noticed that Mr. von Ribbentrop was dining alone and was reading my telegram.

From across the room I could see it was my message for I used a special yellow paper I bought in Finland. I walked over, presented myself saying:

“Mr. Minister I notice you are reading a message of mine which I forwarded only a few hours ago. Because of the difference of time between Koenigsberg and Chicago I can make any changes you may wish to suggest.”

The minister asked me to wait a moment and continued to read with a wry smile, for Gauleiter Koch had spoken about a number of questions concerning foreign relations and policies. When he finished he said he had no changes to suggest and the story could stand as it was written. I then asked one question: Did the agreement he had just signed in Moscow change or affect in any way the status quo of the Baltic States?

[Page 60]

He said it did not. I asked if I could forward this statement to my newspaper and he said I could.

That evening I spent in company with a number of German journalists and National Socialist agents of various kinds. One was a youthful professor who had just returned from a journey through the Far East. His descriptions of the various places he had visited there were frequently interspersed with the remark:

“And how they hate us there.”

I at last interrupted him saying I had also traveled a bit and knew many people in many different countries. I had found that the Germans and their culture were respected everywhere and true enough, in many countries, the Germans were not popular. I ventured the opinion that one of the chief reasons for this dislike was the German’s love of work. They worked so incessantly and so hard that other people had to keep on their toes to compete with them. I told the professor that people who go about boasting how much they were hated generally ended up, not being hated, but by being despised and suggested we change the subject of conversation.

So we turned to the war that seemed only hours away.

On my way to my room that evening a man in civilian dress approached saying “Gestapo, your passport please.” I handed it over and went to bed. In the morning I wrote a note to my friend the Gauleiter and shortly before noon he phoned, asking me to visit him. He handed me back my passport saying he could not tell me why it had been taken. I asked for the two letters he offered to give me; one introducing me to all East Prussian officials asking that I be granted consideration and assistance in gathering and forwarding my news and, second; a personal note to Gauleiter Forster of Danzig, whom I already knew, requesting him to grant me similar help in Danzig. The Gauleiter said he could not give me those letters and when I asked the reason he asked if I had not read the papers that morning. I recalled a brief announcement placing all Germany under martial law. Such credentials could now only be obtained from military authorities. I had noticed that morning the numerous brown-uniformed Nazi officials seemed to have disappeared. In their place were many thousands of men wearing army uniforms on their way to report to various mobilization points in Koenigsberg.

I bid the Gauleiter farewell, for I intended to proceed to Danzig to witness the opening of the war. While paying the taxi in front of the hotel, another Gestapo man asked for my passport. I told him I had just received it back from the Gaulieter. He said he had orders to take it, so we went over to Gestapo headquarters where I was received by an official. He told me they knew of my efforts to rent a car to travel to Danzig and said I was not going to be permitted to go there. I asked why. He said:

[Page 61]

“Mr. Day, we know of your relations with the Polish government. If something should happen to you in Danzig it would not be the fault of the Poles there, but would be blamed upon the Germans. We cannot take any risks. Therefore we cannot permit you to go to Danzig and you had better leave Koenigsberg.”

I thanked him for this unexpected protection from an unawaited danger, and asked if this was to be interpreted as a command or a suggestion.

He said it was merely a suggestion. I said since I could not go to Danzig I preferred to wait in Koenigsberg a few days and he could keep my passport and I would return for it when intending to leave.

The atmosphere between Poland and Germany continued to grow more tense. I was afraid that despite Moscow’s refusal to join the Allies plan to attack Germany from the north and through the Baltic that Poland would make a desperate effort to break through Lithuania to Libau and cut me off from Riga, so I decided to return home. Two afternoons later, when the train left Koenigsberg, we passed long hospital trains with the Red Cross markings and neat, efficient looking nurses on the sidings. The girls waved us a cheerful farewell.

In the Baltic States people clung to the hope that the war would not spread further north in Europe. The Jewish, Bolshevik and British propagandists (I list them according to their importance) had done their work well. There was no sympathy for Germany, but there was still less for Poland. The dislike for Poland was so general that, up to the time of the complete occupation of that country by German and Soviet forces, nowhere in Europe was started a collection to help Polish war sufferers.

More than a hundred Polish military planes landed on Latvian airfields from Polish military aerodromes in the Vilna corridor. I noted the machine gun belts were filled with bullets. The machines were ready for action.

They fled to Latvia, many of the pilots bringing their wives, without firing a shot. When questioned they said they had received no orders. The Polish army had adopted the French army’s system of commands which proved antiquated for mechanistic warfare.

Poland’s military leaders, who boasted that fortifications within Poland were unnecessary because Polish strategy was based on attack, proved just as incompetent as the Polish government. Poland, after all, revealed she was just a pushover. Her dream of becoming a European great power, of acquiring more territory from other nations, of participating in a glorious victory march through the streets of Berlin, shattered like the empty vodka bottle tossed from the cart of a Polish peasant on his way home from market. Poland got drunk on history .. And history, no matter how proud and glorious it may be, is not enough to equip a nation for warfare. Some practical ability is also required. This was one of the several qualities making for true greatness which Poland lacked.

[Page 62]

While Germany was facing England and France and preparing her next blow, Moscow was laying its plans to acquire the Baltic States. The repatriation of the German-Baits alarmed many and some thousands of Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian families, most of whom had lost members in the Bolshevik occupation of 1919, applied also for permission to enter Germany. In the great majority of cases these applicants were accepted. Others believed that since the Baltic States were such a large producers of food stuffs and since it was vital to Germany to protect all available sources of provisions, Berlin would still be able to protect their little countries from Soviet ambitions.

If the German army had moved into the Baltic and garrisoned these countries like the Soviets I am sure they would have been received with hatred, whereas the Red Army was received only with horror. Hatred was born later. Then the Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians realized too late that the amiable, easy-going, Czarist Russia was extinct. Then they discovered their happy prosperous little countries had fallen into the clutches of a monster, not conceived and controlled by a Frankenstein, but by a “Finklestein.”

_______________________

NOTES

* Images (maps, photos, etc.) have also been added that were not part of the original Noontide edition.

__________________

Knowledge is Power in Our Struggle for Racial Survival

(Information that should be shared with as many of our people as possible — do your part to counter Jewish control of the mainstream media — pass it on and spread the word) … Val Koinen at KOINEN’S CORNER

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 1: Reviews; Background Information

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 2: Introduction; Permit Me to Introduce Myself

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 3: Why I Did Not Go Home; The U.S.

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 4: Lativa

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 5: Meet the Bolsheviks

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 6: Alliance With the Bear

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 7: Poland

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 8: Trips; The Downfall of Democracy

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 9: Jews

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 10: Russia

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 11: Lithuania

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 12: Danzig; Lithuania

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 13: Sweden; Norway

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 14: Finland

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 15 (last) : England; Europe; Epilogue; Index of Names

PDF of this blog post. Click to view or download (2.6 MB).

>> Onward Christian Soldiers by Donald Day – Part 06

Version History

Version 2: Dec 8, 2019 — Re-uploaded images and PDF for katana17.com/wp/ version

Version 1: Published Mar 15, 2015

waiting patiently for part 7! 😀

OK, just for you gigi, I’ve put it up a a bit earlier!

🙂 Thanks! 🙂

Pingback: Onward Christian Soldiers - Part 3: Why I did not go Home; The U.S. - katana17katana17

Pingback: Onward Christian Soldiers - Part 5: Meet the Bolsheviks - katana17katana17

Pingback: Onward Christian Soldiers - Part 14: Finland - katana17katana17