Into the Darkness:

An Uncensored Report from

Inside the Third Reich at War

by Lothrop Stoddard

Chapter 13: Women of the Third Reich

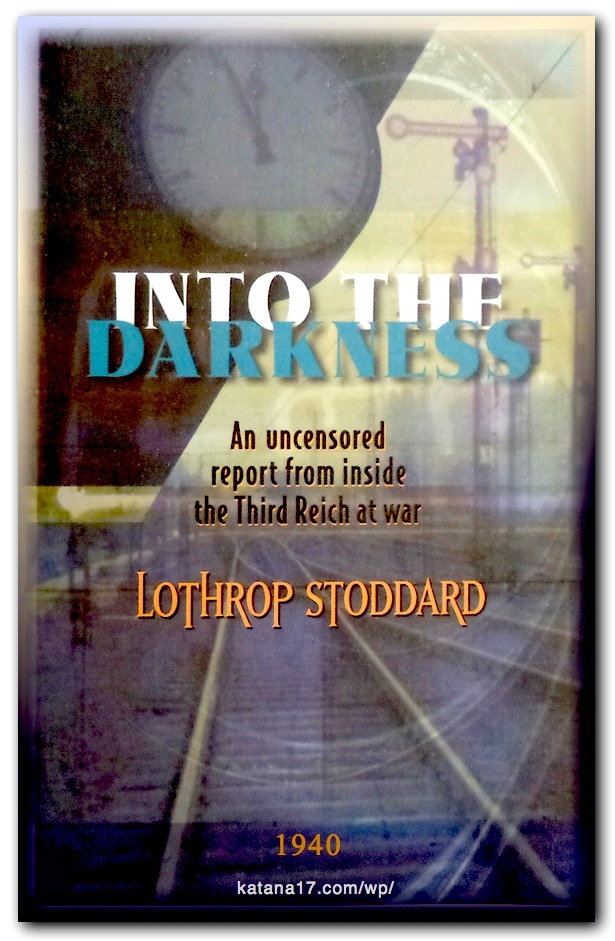

The leader of the women’s wing of the Nazi regime is Frau Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, [1] who set forth that aspect of the Third Reich in an interview she gave me. This conversation came as the climax to several studies I had made of various women’s activities under the guidance of purposeful lady subordinates. Those manifold activities are managed by the Reichsfrauenfuehrung, a compound word which means the Directing Center of German Women’s organizations. The combined membership of these societies totals fully 16,000,000. From this central point in Berlin, directive guidance reaches out to every portion of the Reich.

It was a bitter mid-winter afternoon when I hopped from my taxi and scurried for the entrance of national headquarters, an extensive building situated in Berlin’s West End. The air was full of driving snow whipped by a high wind. I was glad to find shelter in the warm entrance hall, though I could scarcely make my way through a litter of hand luggage and a crowd of women bundled up as though for a trip to the Arctic regions. I was later informed that they were a party of trained nurses and social workers bound for Poland where they would care for a convoy of German-speaking immigrants being repatriated from the Russian-occupied zone. Mute testimony, this, of the multifarious activities of the Reichsfrauenfuehrung, alike in peace and in war.

[Image] Gertrud Scholtz-Klink later known as Maria Stuckebrock (9 Feb,1902 – 24 Mar, 1999) was a fervent NSDAP member and leader of the National Socialist Women’s League (NS-Frauenschaft) [2] in NS Germany.

A dynamic lady, whose mother is an American, Dr. Marta Unger soon appeared and guided me up stairs and through corridors to her chief’s outer office. Presently we were admitted to the inner sanctum, a pleasant reception-room, tastefully furnished. As we entered, the famous women’s leader stood awaiting us.

Frau Scholtz-Klink was rather a surprise to me. I had often seen pictures of her, but they were not good likenesses. She must photograph badly, for they all made her out to be a serious, aloof person well into middle life. When you actually meet her, the first impression she makes on you is one of youthful energy. She was then just thirty-six. A compact woman of medium height, she walks to meet you with an easy, swinging gait and gives you a firm handshake. She is quite informal and as she warms to her subject, her face lights up beneath its crown of abundant blonde hair wound about her head in Marguerite braids. She never gets too serious and laughs easily.

I started the conversation by telling her some of the organizational activities I had seen, and asked her what was the basic idea on which they were conducted. Unhesitatingly, she answered:

“Encouraging initiative. You can’t just command women. You should give them guiding principles of action. Then, within this framework, let them function with the thought that they themselves are the creators and fulfillers of those ideas.”

This rather surprised me, and I told her so, remarking that in America there is a widespread impression that woman’s position is less free in National Socialist Germany than it was under the Weimar Republic, and that this is especially true regarding women’s professional opportunities and political rights.

Frau Scholtz-Klink smiled, nodded understandingly, and came back with the quick retort:

“That depends on what you mean by political rights. We believe that anyone, man or woman, thinks politically who puts the people’s welfare ahead of personal advantage. What does it matter if five or six women are members of Parliament, as was the case in the Weimar regime? We think it vastly more important that, today, sixteen million women are enrolled in our organization and that half a million women leaders have a weighty voice in everything which concerns women and children, from the Central Government and the Party down to the smallest village.” “How about professional opportunities,” I put in. “Are German women still in the universities and in lines like higher scientific work?” “They certainly are,” she replied, “and we are glad to see them there. It is true that when we first came to power seven years ago, some National Socialists were opposed to this because they had been prejudiced by the exaggerately feminist types of women who were so prominent under the Weimar Republic. Today, however, this prejudice has practically vanished. If occasionally we run across some man with an anti-feminist chip on his shoulder, we just laugh about him and consider him a funny old has-been out of touch with the times.” “That’s interesting,” I ventured.

“But it’s easy to understand,” rejoined Frau Scholtz-Klink, “when you recall our basic attitude and policy. Unlike many women’s organizations elsewhere, we don’t fight for what is often called ‘women’s rights.’ Instead, we work hand-in-hand with our menfolk for common aims and purposes. We think that rivalry and hostility between the sexes are as foolish and mutually harmful as they are scientifically unsound. Men and women have somewhat different capacities, but these should always be regarded as complementing and supplementing each other — organic parts of a larger and essentially harmonious whole.” “Then woman’s part in the Third Reich, while consciously feminine, is not feminist?” was my next query.

“Precisely,” she nodded. “We consider it absolutely vital that members of a woman’s organization always remain womanly and do not lose touch with their male colleagues. How long do you think I could stand it if I were shut up here with several hundred woman all the time? Why, I wouldn’t stay here three days! No, no, I can assure you our organization isn’t run like a nunnery. We foregather frequently with our masculine collaborators in informal meetings where we chat and joke together over our weightiest problems.” “Tell me a bit more about your organization,” I suggested.

Frau Scholtz-Klink thought for a moment; then proceeded:

“We National Socialist women didn’t start out with any cut-and-dried program or preconceived theories. When we came to power seven years ago, our country was in terrible shape and we had very little to work with. So we began in the simplest way, busying ourselves with immediate human needs. All the elaborate structure you see today has been a natural evolution — a spontaneous growth.” “How about your outstanding personalities?” I inquired.

Smilingly she shook her head. “We distinctly play down the personalities,” she deprecated. “In our opinion, thinking of person implies that one is not thinking of principle. Take me, for example. I assure you that I really don’t care whether, fifty years hence, when our present goal has been splendidly attained, people remember just who it was that started the ball rolling and helped it on its way.” “What are your relations with women’s organizations in other lands?” I queried.

“We are not internationalists as the term is often used abroad,” Frau Scholtz-Klink answered. “We concern ourselves primarily with our own problems. Of course we are only too glad to be in contact with women from other countries. Indeed, we have a fine guest-house here in Berlin where women visitors can come and stay as long as they like, seeing and studying all we do. If they approve, so much the better. We have no patents. In this sense, therefore, I believe we have a most effective women’s organization. But we have not yet seen our way clear to joining the International Women’s Council.”

Behind that official statement of the viewpoint of Nazi womanhood lies one of the most interesting stories in the evolution of the Third Reich.

Under the old Empire, conservative views prevailed in the field of domestic relations. The man was very much the head of his family. Woman fulfilled her traditional role of wife and mother. Kaiser Wilhelm described woman’s sphere as bounded by the:

“Three K’s, Kinder, Kueche, Kirche — children, kitchen, church.”

Most of his subjects apparently agreed with him. Some sharp dissent there was, and it was not legally repressed. But these dissenters were a relatively small minority.

When the Empire perished, domestic relations were in a turmoil. Liberal and radical ideas on woman’s status became common, all markedly individualistic in character. Women were given the ballot and went actively into politics. Advanced feminist types appeared, intent on developing their personalities and seeking careers outside the home. The “emancipated” woman seemed to be setting the tone.

These radical trends might have survived in an atmosphere of political stability and economic prosperity. But the times were neither stable nor prosperous. When the world depression hit Germany at the close of the 1920’s, conditions became desperate. In this chaotic atmosphere, National Socialism waxed strong and finally prevailed.

One of the first tasks of the Nazi revolution was to sweep away all the new ideas concerning domestic relations. Adolf Hitler had pronounced views on the subject. In one of his campaign pronouncements he stated:

“There is no fight for man which is not also a fight for woman, and no fight for woman which is not also a fight for man. We know no men’s rights or women’s rights. We recognize only one right for both sexes: a right which is also a duty — to live, work, and fight together for the nation.”

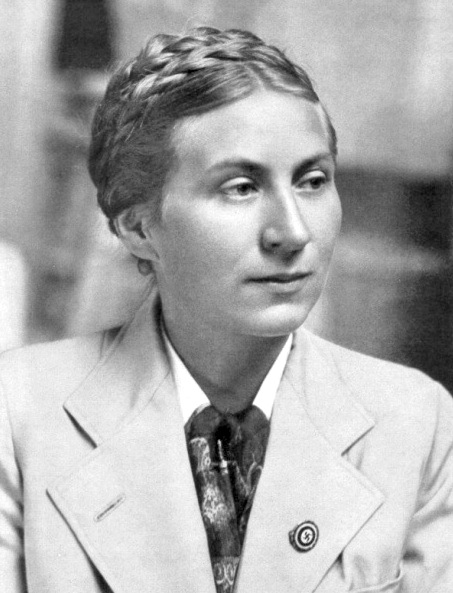

[Image] Frau Scholtz-Klink at the podium giving a speech [3]

In this forthright attitude, Hitler apparently had a large section of German women on his side. From the very start of the Nazi movement, women took a prominent part and were numbered among the Fuehrer’s most devoted followers. These women declared they wanted neither “equality” nor “women’s rights.” What they were after was a home. For the mass of German women, “emancipation” had meant little except hard work at meager wages, and the idea went completely sour with them when economic depression made countless unemployed men dependent upon their womenfolk. Thus, any program which promised confidently to change this abnormal situation could count on enthusiastic support from many women as well as from men.

That was just what National Socialism did promise with its pledge to re-establish the traditional order of domestic relations. It painted an alluring picture of a regime of manly men and womanly women — the manly men as provider and fighter; the womanly woman as wife, mother, and guardian of the domestic hearth.

According to Nazi economic theory, woman’s natural career is marriage. By following the delusive path of Liberal-Marxist materialism, said Hitler, woman herself had been the chief victim. Having invaded business, industry, and the professions, women threw men out of jobs and became their competitors instead of their helpmeets and companions. In so doing, women not only robbed themselves of their crowning happiness (a home and children) but also became largely responsible for the economic crisis which ultimately left women financially worse off than before. When both men and women turned into producers, there were not enough consumers left to consume what they produced.

[Image] Gertrud Scholtz-Klink with Adolf Hitler

That was the Nazi theory. And it caught on like wildfire. Nazi women orators denounced the Weimar regime as having degraded German womanhood into “parasites, pacifists, and prostitutes.” It was these feminine zealots who converted their sisters wholesale. The “Woman’s Front” of the Nazi movement soon became one of its most influential branches. And the interesting point is that it was run by the women themselves.

The activities of this Woman’s Front are complex and far-reaching. They overlap into many fields which we have already surveyed, such as the feminine sectors of the Labor Service and the Hitler Youth, together with phases of the great social-service enterprise known as NSV, which we will describe in the next chapter.

Its earliest enterprise was the Muetterdienst, or Mothers’ Service — a network of adult schools giving courses of instruction in infant care, general hygiene, home nursing, cooking, sewing, and the beautification of the home itself. Permanent quarters are established in all cities and large towns, while itinerant teachers conduct courses in villages and the remotest countryside. The system has now reached throughout the Reich, and several million women have passed through this domestic education — an intensive course with classes limited to twenty-five persons, since instruction takes the form, not of theoretical lectures, but of practical teaching by actual demonstration in which the pupils take part. Alongside these courses for housewives are others for prospective brides.

Most foreign observers agreed that this domestic education has helped many German women to be better wives and mothers. I myself investigated the large Mother School established in Wedding, a Berlin suburb inhabited by working folk. This institution also serves as a sort of normal school where teachers are trained. I met and talked with the members of the current class, drawn from all parts of Germany. They appeared to be earnest, capable young women, well chosen for their future jobs.

Another major field of service is in industry, where trained “confidence women” actually work in factories, stores, and offices employing much female labor. These women are thus in personal touch with working conditions. Naturally, such women are the best sort of propagandists for the Party and its ideas. Still other fields of activity might be described if space permitted in a general survey like this. At least half a million women are actively engaged in these various lines of endeavor.

This, of course, is the answer which Frau Scholtz-Klink and her colleagues make to the charge that National Socialism has driven women out of public life. They claim that it has changed the nature of those activities to more fruitful channels. As a matter of fact, the whole economic trend in the Third Reich, by transforming mass unemployment into an acute labor shortage, has driven women into all sorts of activities outside the home circle — which is certainly not what Hitler promised his feminine followers. It is estimated that nearly 12,000,000 women were gainfully employed in the Reich when war broke out, and that figure will undoubtedly be vastly exceeded as men are continually mobilized for war service. Yet, in these new developments, it is probable that the Nazi attitude and policy will remain basically unaltered.

———————————-

Footnotes:

[1] Gertrud Scholtz-Klink later known as Maria Stuckebrock (9 February 1902 – 24 March 1999) was a fervent NSDAP member and leader of the National Socialist Women’s League (NS-Frauenschaft) in NS Germany.

She married a factory worker at the age of eighteen and had six children before he died.

Scholtz-Klink joined the NS Party and by 1929 became leader of the women’s section in Berlin. In 1932, Scholtz-Klink married Guenther Scholtz, a country doctor (divorced in 1938).

When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, he appointed Scholtz-Klink as Reich’s Women’s Führerin and head of the NS Women’s League. A good orator, her main task was to promote male superiority, the joys of home labour and the importance of child-bearing. In one speech, she pointed out that;

“the mission of woman is to minister in the home and in her profession to the needs of life from the first to last moment of man’s existence.”

Despite her own position, Scholtz-Klink spoke against the participation of women in politics, and took the female politicians in Germany of the Weimar Republic as a bad example, saying, “Anyone who has seen the Communist and Social Democratic women scream on the street and the parliament, realize that such an activity is not something which is done by a true woman”. She claimed that for a woman to be involved in politics, she would either have to “become like a man”, which would “shame her sex”, or “behave like a woman”, which would prevent her from achieving anything.

In July 1936, Scholtz-Klink was appointed as head of the Woman’s Bureau in the German Labor Front, with the responsibility of persuading women to work for the benefit of the Nazi government. In 1938, she argued that;

“the German woman must work and work, physically and mentally she must renounce luxury and pleasure”.

Scholtz-Klink was usually left out of the more important meetings in the male-dominated society of the Third Reich, and was considered to be a figurehead. She did, however, have the influence over women in the party as Hitler had over everyone else.

[Image] The combined families of Scholtz-Klink and her third husband August Heissmeyer

By 1940, Scholtz-Klink was married to her third husband SS-Obergruppenführer August Heissmeyer, and made frequent trips to visit women at Political Concentration Camps.

Post-war life

At the end of World War II Scholtz-Klink and Heissmeyer fled from the Battle of Berlin. After the fall of the Third Reich, in the summer of 1945, she was briefly detained in a Soviet prisoner of war camp near Magdeburg, but escaped shortly after. With the assistance of Princess Pauline of Württemberg, she and her third husband went into hiding in Bebenhausen near Tübingen. They spent the subsequent three years under the aliases of Heinrich and Maria Stuckebrock.

On 28 February 1948, the couple were identified and arrested. A French military court sentenced Scholtz-Klink to 18 months in prison on the charge of forging documents. In May 1950, a review of her sentence classified her as the “main culprit” and sentenced her to additional 30 months. In addition, the court imposed a fine and banned her from political and trade union activity, journalism and teaching for ten years.

After her release from prison in 1953, Sholtz-Klink settled back in Bebenhausen.

In her 1978 book Die Frau im Dritten Reich (“The Woman in the Third Reich”), Scholtz-Klink demonstrated her continuing support for the National Socialist ideology. She once again upheld her position on National Socialism in her interview with historian Claudia Koonz in the early 1980s.

She died on 24 March 1999 in Bebenhausen, Germany.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gertrud_Scholtz-Klink

[2] The National Socialist Women’s League (German: Nationalsozialistische Frauenschaft, abbreviated “NS-Frauenschaft”) was the women’s wing of the NS Party. It was founded in October 1931 as a fusion of several nationalist and National Socialist women’s associations.

The Frauenschaft was subordinated to the national party leadership (Reichsleitung); girls and young women were the purview of the Bund Deutscher Mädel (BDM). From February 1934 to the end of World War II in 1945, the NS-Frauenschaft was led by Reich’s Women’s Leader (Reichsfrauenführerin) Gertrud Scholtz-Klink (1902–1999). It put out a biweekly magazine, the NS-Frauen-Warte.

Its activities included instruction in the use of German-manufactured products, such as butter and rayon, in place of imported ones, as part of the self-sufficiency program, and classes for brides and schoolgirls. During wartime, it also provided refreshments at train stations, collected scrap metal and other materials, ran cookery and other classes, and allocated the domestics conscripted in the east to large families. Propaganda organizations depended on it as the primary spreader of propaganda to women.

The NS-Frauenschaft reached a total membership of 2 million by 1938, the equivalent of 40% of total party membership.

The German National Socialist Women’s League Children’s Group was known as “Kinderschar”.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Socialist_Women’s_League

[3] Speech given by:

FRAU GERTRUD SCHOLTZ-KLINK

Reich Women’s Leader

When National Socialism became the ruling power in Germany (1933), we women realized that it was our duty to contribute our share to the Leader’s reconstruction programme side by side with men. We did not say much about it, but started to work at once. Our first concern was to help all those mothers who had suffered great hardships during the War and the post-war period and all those other women who — as mothers — have now to adjust themselves to the demands of the new age.

Acting in accordance with the recognition of these facts, we first created the Reich Mothers’ Service (Reichsmütterdienst), the functions of which are set forth in Article I of the regulations governing it:

The training of mothers is animated by the spirit of national solidarity and by the conviction that they can be of very great service to the nation and the State. The object of such training is to develop the physical and intellectual efficiency of mothers, to make them appreciate the great duties incumbent upon them, to instruct them in the upbringing and education of their children, and to qualify them for their domestic and economic tasks.

In order to provide such training, several courses of instruction have been drawn up, each of which deals with one particular subject only, e.g., infant care, general hygiene, sick nursing at home, children’s education, cooking, sewing, etc. These courses are fixtures in all towns with a population exceeding 50,000, whilst itinerant teachers conduct similar ones in the smaller towns and in the country. Every German woman over 18 can join them, irrespective of her religious, political or other views. The maximum number of members has been limited to 25 for each course, because the instruction given does not consist of theoretical lectures, but takes the form of practical teaching to working groups, where questions will be asked and answered.

Since the establishment of the Reichsmütterdienst, i.e., between April 1st, 1934, and October 1st, 1937, some 1,179,000 married and unmarried women have been thus instructed in 56,400 courses, conducted by over 3,000 teachers of whom about 1,200 are employed full-time, whilst the remaining 2,300 (also possessing the necessary qualifications) act in an honorary capacity or in that of part-time instructresses.

Our next concern was with those millions of German women who, day after day, attend to their heavy duties in factories. We look upon it as most important to make them realise that they, too, are the representatives of their nation. They, too, must take pride in their work and must be able to say:

“I have a useful duty to fulfil; and the work I do is an essential part of the work performed by the whole nation.”

With this end in view, we have created the Women’s Section of the German Labour Front (Frauenamt der Deutschen Arbeitsfront), which has now a membership of over 8,000,000. Foreign critics have frequently stated that German women have no chance of earning their livelihood by working in industrial or other undertakings. I therefore take this opportunity of emphasising that more than 11,500,000 women are employed in the various professions and occupations; the Women’s Section of the German Labour Front attending to their interests. Moreover, we are of the opinion that a woman will always find it possible to secure paid employment provided that she is strong enough to do the work demanded of her. This applies to women workers of all categories, irrespective of whether the work is of the physical or intellectual kind. It is therefore the business of the Frauenamt to ensure that women are not employed in any capacity that might prove detrimental to their womanhood and to give them all the protection to which they are specifically entitled.

In order to translate these ideas into practice, the Frauenamt has proceeded to appoint a “social industrial woman worker” (soziale Betriebsarbeiterin) for every undertaking in which a considerable number of women are employed. The functions to be exercised by these Betriebsarbeiterinnen are of a general and a special kind. They have to see to it that all women employed in the same undertaking look upon their own interests as identical with those of the latter and that a proper spirit of comradeship grows up among them.

They are assisted in their task by the works’ leader and the confidential council, and they are in a position to gain the confidence of the other women workers because all of them are comrades of one another. They have to prevent strife, jealousy, and irresponsible talk from poisoning the social atmosphere of the works, to help those of their fellow-workers who may be oppressed by domestic worries, and to assist in rendering the conditions of work as dignified as possible. To that end, they have to furnish the works’ leader with suggestions for any measures that may be required to adapt the processes of work – in conformity with the technical peculiarities of the undertaking – to the natural capacities of women. Finally, they have to assist in the transfer of women workers to other places of employment, in the task of making the aspect of the working premises as pleasing as possible, etc.

This enumeration of their functions shows that they must not only be experienced social workers, but must also be familiar with the actual work. For this latter reason, they are required to devote several months to such work before they are appointed to the post of social workers. During that time they receive the same wages as the other women workers and are subject to the same regulations as they. Similar arrangements, although on a more modest scale, are made in connection with smaller works, i.e., those where the number of women workers is less than 200.

Special care is devoted by our organisation to married women workers with children and to those expecting to be confined. In this domain of social work we provide assistance, in conjunction with the National Socialist Welfare Organisation (N.S. Volkswohlfahrt), exceeding the standards set by the existing legislation. Such supplementary assistance consists in money, food, linen, etc.

I must not omit to add a few words in reference to the women students who spend part of their holidays for the benefit of those women workers — notably those who have large families — who are in need of a week’s relaxation in addition to their regular holidays. The students generously attend to the factory work of these women during their absence; and as they demand no wages, the workers suffer no pecuniary loss whatever. In many instances, free quarters are provided for the students by the National Socialist Women’s Organisation (N.S. Frauenschaft), whilst the Welfare Organisation grants special facilities to the women on holiday, such as additional food parcels, board and lodging in one of their mothers’ hostels and so on. During the first few years of the operation of the scheme, the students relieved the workers to the extent of 57,700 days’ work. Large numbers of letters are received by us every day, in which workers and students alike tell us how grateful they are for their unforgettable experience. Works’ leaders, too, continually inform us of the beneficial results achieved.

After completing the inauguration of the above schemes, we continued our work in a different direction, i.e., by organising ourselves. We have now co-ordinated the previously existing women’s associations and thus created the German Women’s Association (Deutsches Frauenwerk), which is sub-divided into sections along the lines laid down by the N.S. Frauenschaft.

The Deutsches Frauenwerk consists, apart from the Mothers’ Service already mentioned, of the following sections: National and domestic economy; cultural and educational matters; assistance, and a foreign section. In addition, there are four large administrative departments, viz., general administration; finances; organisation and staff; the Press and propaganda matters, which latter also deals with the radio, films, and exhibitions.

In the section for national and domestic economy, women and girls are trained to apply the principles of national solidarity. They are taught that, in every household, the mother is responsible for the health of the whole family by providing good food and by generally exercising her duties with skill and efficiency.

The cultural and educational section makes the nation’s cultural assets available to women; women artists are assisted in their work, and particular attention is paid to the achievements of women in the realm of science.

The assistance section deals with the work done by female nurses, the Red Cross, and the air defence society.

The foreign section establishes contact with women’s associations abroad, supplies information to foreigners, exchanges experiences with foreign organisations, makes arrangements for seeing the institutions in connection with the work of the Deutsches Frauenwerk, etc.

All these groups are under the general direction of the N.S. Frauenschaft, which may therefore be regarded as the leading organisation, whilst the Deutsches Frauenwerk and the Frauenamt der Deutschen Arbeitsfront constitute the joint foundation for the work done by women throughout the country.

Foreigners have repeatedly asked me about the kind of compulsion exercised to make women take part in all this work. I wish to assure inquirers that we know of no compulsion whatever. Those who want to join us, must do so absolutely voluntarily; and I can only say that all of them are joyfully devoted to their work.

Let me conclude by quoting a remark which I made on the occasion of the Women’s Congress held at the time of the Nuremberg party rally (1935):

“All the work done by us as a matter of course, which is now so comprehensive that we cannot any longer describe it in detail, is only a means to an end. It is the expression of the determination of German women to assist in solving the great problems of our age. A spirit of comradeship animates all of us; and our devotion to our nation guides all our efforts.”

—————————

Source: http://nseuropa.wordpress.com/2012/11/11/the-place-of-women-in-the-new-germany/

———————————-

Chapter 1: The Shadow

Chapter 2: Berlin Blackout

Chapter 3: Getting on with the Job

Chapter 4: Junketing Through Germany

Chapter 5: This Detested War

Chapter 6: Vienna and Bratislava

Chapter 7: Iron Rations

Chapter 8: A Berlin Lady Goes to Market

Chapter 9: The Battle of the Land

Chapter 10: The Labor Front

Chapter 11: The Army of the Spade

Chapter 12: Hitler Youth

Chapter 13: Women of the Third Reich

Chapter 14: Behind the WinterHelp

Chapter 15: Socialized Health

Chapter 16: In a Eugenics Court

Chapter 17: I See Hitler

Chapter 18: MidWinter Berlin

Chapter 19: Berlin to Budapest

Chapter 20: The Party

Chapter 21: The Totalitarian State

Chapter 22: Closed Doors

Chapter 23: Out of the Shadow

===========================

PDF of this post. Click to view or download (0.8MB). >>Into the Darkness – Chap 13 – Ver 2

Knowledge is Power in Our Struggle for Racial Survival

(Information that should be shared with as many of our people as possible — do your part to counter Jewish control of the mainstream media — pass it on and spread the word) … Val Koinen

———————————-

PDF of this post (click to download or view): Into the Darkness – Chap 13 – Ver 2

Version History

Version 7: May 13, 2022 – Re-uploaded images and PDF. Improved formatting.

Version 6: Nov 28, 2014. Added PDF file (Ver 2) of this post.

Version 5: Nov 27, 2014 – Added PDF of post

Version 4: Aug 31, 2014. Formatted text.

Version 3: Aug 30, 2014. Added images and footnotes. Added PDF download.

Version 2: Wed, Feb 5, 2014. Added Chapter links.

Version 1: Published Jan 24, 2014 – Text added.

Reblogged this on A White Woman's Perspective.

Thanks Tina for reblogging the post.

Pingback: Into the Darkness : Chapter 3 – Getting on with the Job | katana17

Pingback: Into the Darkness : Chapter 6: Vienna and Bratislava | katana17

Pingback: Into the Darkness : Chapter 7: Iron Rations | katana17

Pingback: Into the Darkness : Chapter 8: A Berlin Lady Goes to Market | katana17

Pingback: Into the Darkness : Chapter 9: The Battle of the Land | katana17

Pingback: Into the Darkness : Chapter 11: The Army of the Spade | katana17

Pingback: Into the Darkness : Chapter 12: Hitler Youth | katana17