The Slave Trade in the Congo Basin

PART 1

By One of Stanley’s Pioneer Officers.

Illustrated After Sketches from Life by the Author

This article was originally published in

The Century Magazine — April, 1890.

Contents

WITH STANLEY

NATIVE LIFE

THE EFFECT OF SLAVERY

THE VILLAGE CHIEFS

MODES OF TORTURE

HOW THE NATIVES ARE ENSLAVED

IN THE SLAVE SHED

CANNIBALISM

LOCAL SLAVE-MARKETS

IN THE FAR INTERIOR

SOME BARBAROUS CUSTOMS

SUPPRESSION OF SLAVERY

EFFECT OF LIBERATION

WITH STANLEY

The heart of Africa is being rapidly depopulated in consequence of the enormous death-roll caused by the barbarous slave-trade. It is not merely the bondage which slavery implies that should appeal to the sympathies of the civilized world; it is the bloodshed, cruelty, and misery which it involves.

During my residence in Central Africa I was repeatedly traveling about in the villages along the Congo River and its almost unknown affluents, and in every new village I was confronted by fresh evidences of the horrible nature of this evil. I did not seek to witness the sufferings attendant upon this traffic in humanity, but cruelties of all kinds are so general that the mere passing visits which I paid brought me in constant contact with them.

[Click to open a larger image in a new window]

It is not alone by the Arabs that slave-raiding is carried on throughout Central Africa. With respect to slavery in the Congo Free State, the western limit of the slave-raiding operations of the Arabs is the Aruwhimi River, just below Stanley Falls, but intertribal slavery exists from this point throughout the State to the Atlantic Ocean. During my six years’ residence on the Congo River I saw but little of the Arabs, and therefore in this article I am detailing only my experiences bearing upon the subject of slavery among the natives themselves.

I first went to the Congo in 1883, and traveled without delay into the interior. Arriving at Stanley Pool, I received orders from my chief, Mr. Henry M. Stanley, to accompany him up river on his little boat the En Avant. Stanley at that time was engaged in establishing a few posts at important and strategic points along the upper river. Lukolela, eight hundred miles in the interior, was one decided upon, and I had the honor of being selected by him as chief of this post. As no white man had ever lived there before, I had a great deal of work in establishing myself. The position selected for our settlement was a dense forest, and until now it had been more familiar with the trumpeting of elephants and the cry of the leopard than with human beings. At first the natives rather objected to my remaining at all, and stated their objections to Stanley. Said they:

“We have promised to allow you to put a white man here, but we have been talking the matter over, and we have concluded it would be better to put your white man somewhere else. We, the assembled chiefs, have held a council, and have come to the conclusion that it is not desirable to have such a terrible creature in the district.”

Stanley said:

“Why, what is there in him that you object to? You have never seen him.”

(I had not yet landed, being at that time very sick and unable to leave the boat.)

They said:

“No, we have not seen him, but we have heard about him.”

Stanley then said:

“What have you heard about him?”

They replied:

“He is half a lion, and half a buffalo; has one eye in the middle of his forehead, and is armed with sharp, jagged teeth; and is continually slaughtering and devouring human beings. Is this so?”

Stanley answered them,

“I did not know that he was such a terrible creature; but I will call him, and let you judge for yourselves.”

Upon my appearing this illusion was immediately dispelled, as, after suffering several days from an acute sickness, I really did not look very formidable or bloodthirsty.

Here I lived for twenty months, the only white man, so that I had every opportunity of studying native character and customs.

NATIVE LIFE

In order to place before the reader a picture of savage life untouched by civilization, I could hardly do better than lightly sketch a typical village at Lukolela as I have intimately known it. The whole district contains about three thousand people, the land occupied by them extending along the bank for two miles, the villages being dotted through this distance in clusters of fifty or sixty houses. The houses are built on each side of one long street or in open squares. They are roofed with either palm leaves or grass, the walls being composed of split bamboo. Some of these dwellings contain two or three compartments, with only one entrance; while others are long structures, divided up into ten or twelve rooms, each with its own entrance from the outside. At the back of these dwellings are large plantations of banana trees; while above them tower the stately palm trees, covering street and hut with their friendly shade.

It is in the cool of the early morning that the greater part of the business of the village is transacted. Most of the women repair, soon after six, to their plantations, where they work until noon, a few of them remaining in the village to attend to culinary and other domestic matters. Large earthen pots, containing fish, banana, or manioc, are boiling over wood fires, around which cluster the young boys and girls and the few old men and women enjoying the heat until the warm rays of the morning sun appear. Meanwhile the fishermen gather up their traps, arm themselves, and paddle off to their fishing grounds; the hunters take their spears or bows and arrows and start off to pick up tracks of their game; the village blacksmith starts his fire; the adze of the carpenter is heard busily at work; fishing and game nets are unrolled and damages examined; and the medicine man is busy gesticulating with his charms. As the sun rises the scene becomes more and more animated; the warmth of the fire is discarded, and every department of industry becomes full of life — the whole scene rendered cheerful by the happy faces and merry laughter of the little ones as they scamper here and there engaged in their games.

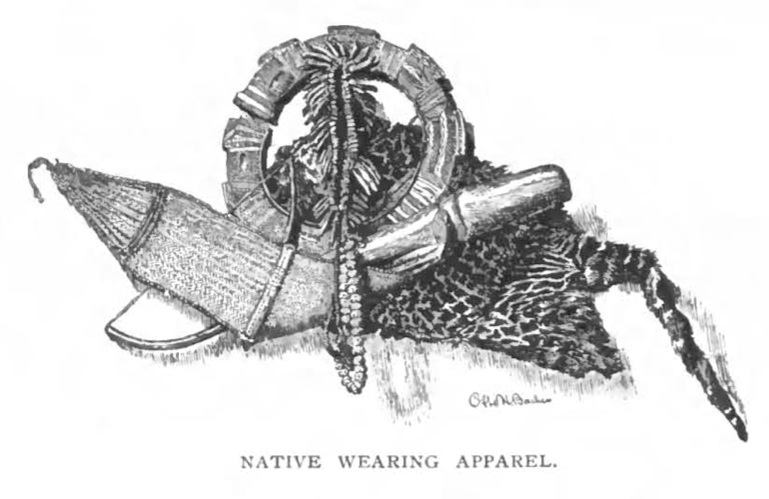

At noon the overpowering heat of the tropical sun compels a cessation of work, and a lazy quietude prevails everywhere. Then all the shady nooks of the village are filled with groups who either sleep, engage in conversation, or pass their time in hairdressing or in attending to some other toilet matter which native etiquette demands, such as shaving off eyebrows or pulling out eyelashes — an operation which is also extended to all hairs on the face except those on the chin, which are plaited in the form of a rat’s tail. The closer the finger nails are cut, the more fashionable is it thought. At the finger ends the nails are cut down to the quick, and any one posing as either beau or belle always has some of the finger and toe nails pared entirely off.

The midday meal is now eaten, the whole village assuming an air of calmness, broken only by the occasional bursts of boisterous mirth from groups engaged in discussing the merits of the native wine.

All mankind have the same weakness in requiring at times drink stronger than water. Nature has provided the African with the juice of the palm tree, a most palatable beverage, resembling when fresh a very strong lemon soda, but intoxicating in its effects. It is obtained in the following way: the villagers in charge of this particular industry climb the tree, trim away some of the leaves, and then bore three or four holes, about half an inch in diameter, at the base of the frond, to the heart of the tree. From each of these holes will flow each day about half a pint of juice, a small gourd being first placed to receive it. The contents of these gourds are collected every morning. This beverage is called by the natives malafu , and is well known to all European travelers as palm wine.

Between three and four o’clock the village again resumes its air of activity, which is kept up until sundown. In this region, being close to the equator, the sun sets at six o’clock. All tools are put away, and work is suspended. The fires are again lighted, mats are brought out and spread about, and the principal meal of the day is eaten; after which the natives gather around the fire again and talk over the events of the day and the plans for the future. The young people repair to the open places and indulge in their native dances until midnight.

This dancing at night is a sight to be remembered. The performers arrange themselves in circles and dance in time to the beating of the drums, which is their only accompaniment, and occasionally break out into native songs. The surrounding tropical scenery stands outlined in bold relief, the nearer trees occasionally catching the lurid light of the fires, which also strikes on the gleaming bodies of the dancers, making a violent contrast of light and shade, the whole scene being rendered impressive by the wild but harmonious music.

At midnight, when all the villagers have retired to their huts, stillness reigns, broken only at times by the weird call of a strange bird, the cry of a prowling leopard or some other wild animal, and the varied sounds of tropical insects.

THE EFFECT OF SLAVERY

This is a fair picture of the life carried on from day to day in a hundred Congo villages, and but for the existence of slavery it would continue undisturbed from one year’s end to another. It is the presence of the slave in the village that brutalizes the otherwise harmless and peaceful community. It is the baneful influence that gives one man the power of life and death over the wretch he has purchased that impels the savage instinct to spill in executions and ceremonies the life-blood of the man, woman, or child he has obtained — perhaps in exchange for a few brass rods or two or three yards of Manchester cloth. Here at Lukolela, for instance, I had hardly settled down in my encampment when I was introduced to one of those horrible scenes of bloodshed which take place frequently in all the villages along the Congo, and which will be enacted so long as the life of a slave is counted as naught, and the spilling of his blood of as little account as that of a goat or a fowl.

In this particular instance the mother of a chief having died, it was decided, as usual, to celebrate the event with an execution. At the earliest streak of dawn the slow, measured beat of a big drum announces to all what is to take place, and warns the poor slave who is to be the victim that his end is nigh. It is very evident that something unusual is about to happen, and that the day is to be given up to some ceremony. The natives gather in groups and begin studiously to arrange their toilets, don their gayest loin-cloths, and ornament their legs and arms with bright metal bangles, all the time indulging in wild gesticulations and savage laughter as they discuss the coming event. Having taken a hasty meal, they produce from their houses all available musical instruments. The drums are wildly beaten as groups of men, women, and children form themselves in circles and excitedly perform dances, consisting of violent contortions of the limbs, accompanied with savage singing and with repeated blasts of the war horns, each dancer trying to outdo his fellow in violence of movement and strength of lung.

About noon, from sheer exhaustion, combined with the heat of the sun, they are compelled to cease; when large jars of palm wine are produced, and a general bout of intoxication begins, increasing their excitement and showing up their savage nature in striking colors. The poor slave, who all this time has been lying in the corner of some hut, shackled hand and foot and closely watched, suffering the agony and suspense which this wild tumult suggests to him, is now carried to some prominent part of the village, there to be surrounded and to receive the jeers and scoffs of the drunken mob of savages. The executioner’s assistants, having selected a suitable place for the ceremony, procure a block of wood about a foot square. The slave is then placed on this, in a sitting posture; his legs are stretched out straight in front of him; the body is strapped to a stake reaching up the back to the shoulders. On each side stakes are placed under the armpits as props, to which the arms are firmly bound; other lashings are made to posts driven into the ground near the ankles and knees.

A pole is now planted about ten feet in front of the victim, from the top of which is suspended, by a number of strings a bamboo ring. The pole is bent over like a fishing-rod, and the ring fastened round the slave’s neck, which is kept rigid and stiff by the tension. During this preparation the dances are resumed, now rendered savage and brutal in the extreme by the drunken condition of the people. One group of dancers surround the victim and indulge in drunken mimicry of the contortions of face which the pain caused by this cruel torture forces him to show. But he has no sympathy to expect from this merciless horde.

Presently in the distance approaches a company of two lines of young people, each holding a stem of the palm tree, so that an arch is formed between them, under which the executioner is escorted. The whole procession moves with a slow but dancing gait. Upon arriving near the doomed slave all dancing, singing, and drumming cease, and the drunken mob take their places to witness the last act of the drama.

An unearthly silence succeeds. The executioner wears a cap composed of black cocks’ feathers; his face and neck are blackened with charcoal, except the eyes, the lids of which are painted with white chalk. The hands and arms to the elbow, and feet and legs to the knee, are also blackened. His legs are adorned profusely with broad metal anklets, and around his waist are strung wild-cat skins. As he performs a wild dance around his victim, every now and then making a feint with his knife, a murmur of admiration arises from the assembled crowd. He then approaches and makes a thin chalk mark on the neck of the fated man. After two or three passes of his knife to get the right swing, he delivers the fatal blow, and with one stroke of his keen-edged weapon severs the head from the body.

The sight of blood brings to a climax the frenzy of the natives: some of them savagely puncture the quivering trunk with their spears, others hack at it with their knives, while the remainder engage in a ghastly struggle for the possession of the head, which has been jerked into the air by the released tension of the sapling. As each man obtains the trophy, and is pursued by the drunken rabble, the hideous tumult becomes deafening; they smear one another’s faces with blood, and fights always spring up as a result, when knives and spears are freely used. The reason for their anxiety to possess the head is this: the man who can retain that head against all comers until sundown will receive a present for his bravery from the head man of the village. It is by such means that they test the brave of the village, and they will say with admiration, speaking of a local hero,

“He is a brave man; he has retained two heads until sundown.”

When the taste for blood has been to a certain extent satisfied, they again resume their singing and dancing while another victim is prepared, when the same ghastly exhibition is repeated. Sometimes as many as twenty slaves will be slaughtered in one day. The dancing and general drunken uproar is continued until midnight, when once more absolute silence ensues, in utter contrast to the hideous tumult of the day.

I had frequently heard the natives boast of the skill of their executioners, but I doubted their ability to decapitate a man with one blow of the soft metal knives they use. I imagined they would be compelled to hack the head from the body. When I witnessed this sickening spectacle I was alone, unarmed, and absolutely powerless to interfere. But the mute agony of this poor black martyr, who was to die for no crime, but simply because he was a slave, — whose every piteous movement was mocked by frenzied savages, and whose very death throes gave the signal for the unrestrained outburst of a hideous carnival of drunken savagery, — appealed so strongly to my sense of duty that I decided upon preventing by force any repetition of this scene. I made my resolution known to an assembly of the principal chiefs, and although several attempts were made, no actual executions took place during the remainder of my stay in this district.

THE VILLAGE CHIEFS

A few words are necessary to define the position of the village chiefs as the most important factors in African savage life; especially as in one way or another they are intimately connected with the worst features of the slave system, and are responsible for nearly all the atrocities practiced on the slave.

The so-called chiefs are the head men of a village, and they rank according to the number of their warriors. The title of chieftain is not hereditary, but is gained by one member of a tribe proving his superiority to his fellows. The most influential chief in a village has necessarily the greatest number of fighting men, and these are principally slaves, as the allegiance of a free man can never be depended upon. A chief’s idea of wealth is — slaves. Any kinds of money he may have he will convert into slaves upon the first opportunity. Polygamy is general throughout Central Africa, and a chief buys as many female slaves as he can afford, and will also marry free women — which is, after all, only another form of purchase.

MODES OF TORTURE

All tribes I have known have an idea of immortality. They believe that death leads but to another life, to be continued under the same conditions as the life they are now leading; and a chief thinks that if when he enters into this new existence that if he is accompanied by a sufficient following of slaves he will be entitled to the same rank in the next world as he holds in this. From this belief emanates one of their most barbarous customs — the ceremony of human sacrifices upon the death of any one of importance. Upon the decease of a chief, a certain number of his slaves are selected to be sacrificed, that their spirits may accompany him to the next world. Should this chief possess thirty men and twenty women, seven or eight of the former and six or seven of the latter will suffer death. The men are decapitated, and the women are strangled. When a woman is to be sacrificed she is adorned with bright metal bangles, her toilet is carefully attended to, her hair is neatly plaited, and bright-colored cloths are wrapped around her. Her hands are then pinioned behind, and her neck is passed through a noose of cord; the long end of the cord is led over the branch of the nearest tree, and is drawn taut at a given signal; and while the body is swinging in mid-air its convulsive movements are imitated with savage gusto by the spectators. It often happens that a little child also becomes a victim to this horrible ceremony, by being placed in the grave alive, as a pillow for the dead chief. These executions are still perpetrated in all the villages of the Upper Congo.

But the life of the slave is not only forfeited at the death of the chief of the tribe in which fate has cast his lot. Let us suppose that the tribe he is owned by has been maintaining an internecine warfare with another tribe in the same district. For some reason it is deemed politic by the chief to bring the feud to an end, and a meeting is arranged with his rival. At the conclusion of the interview, in order that the treaty of peace may be solemnly ratified, blood must be spilled.

A slave is therefore selected, and the mode of torture preceding his death will vary in different districts. In the Ubangi River district the slave is suspended head downwards from the branch of a tree, and there left to die. But even more horrible is the fate of such a one at Chumbiri, Bolobo, or the large villages around Irebu, where the expiatory victim is actually buried alive with only the head left above the ground. All his bones have first been crushed or broken, and in speechless agony he waits for death. He is usually thus buried at the junction of two highways, or by the side of some well-trodden pathway leading from the village; and of all the numerous villagers who pass to and fro, not one, even if he felt a momentary pang of pity, would dare either to alleviate or to end his misery, for this is forbidden under the severest penalties.

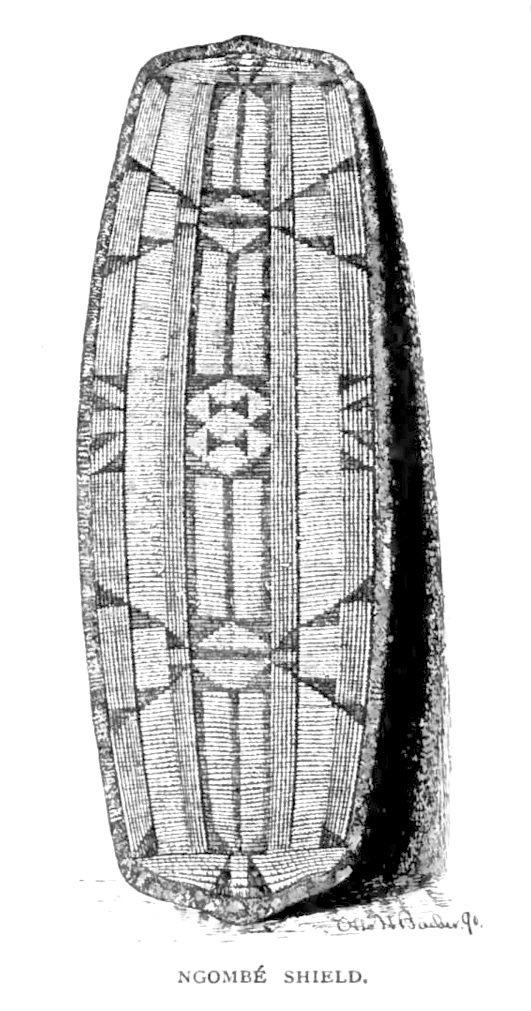

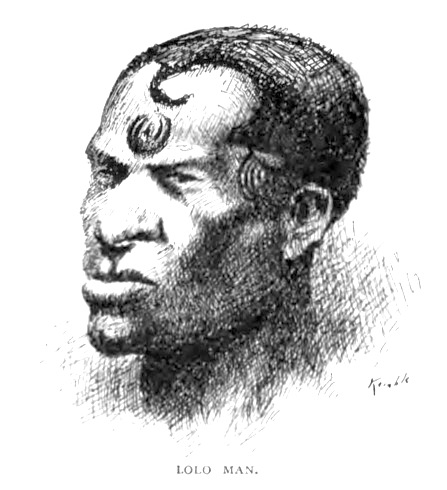

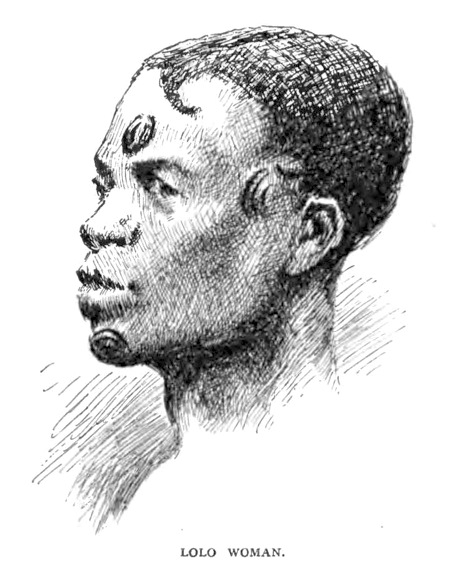

HOW THE NATIVES ARE ENSLAVED

The varying fortunes of tribal warfare furnish the markets with slaves whose cicatrization marks show them to be members of widely differing families and distant villages. But there are some tribes, and these the most inoffensive and the most peaceful, whose weakness places them at all times at the mercy of their more powerful neighbors. Without exception the most persecuted race in the dominions of the Congo Free State are the Balolo tribes, inhabiting the country through which the Malinga, Lupuri, Lulungu, and Ikelemba rivers flow. I may here mention the the prefix “Ba” in the language of these people implies the plural; for instance, Lolo would mean one Lolo — Ba-lolo signifying Lolo people. These people are naturally mild and inoffensive. Their small, unprotected villages are constantly attacked by the powerful roving tribes of the Lufembé and Ngombé. These two tribes are voracious cannibals. They surround the Lolo villages at night, and at the first signs of dawn pounce down upon the unsuspecting Balolo, killing all the men who resist and catching all the rest. They then select the stronger portion of their captives, and shackle them hand and foot to prevent their escape. The remainder they kill, distributing the flesh among themselves.

As a rule, after such a raid they form a small encampment; they light their fires, seize all the bananas in the village, and gorge upon the human flesh. They then march over to one of the numerous slave-markets on the river, where they exchange the captives with the slave-traders of the Lulungu River for beads, cloth, brass wire, and other trinkets. The slave-traders pack the slaves into their canoes and take them down to the villages on the Lulungu River where the more important markets are held. Masankusu, situated at the junction of the Lupuri and Malinga tributaries, is by far the most important slave-trading center. The people of Masankusu buy their slaves from the Lufembé and Ngombé raiders, and sell them to the Lulungu natives and traders from down river. The slaves are exhibited for sale at Masankusu in long sheds, or rather under simple grass roofs supported on bare poles. It is heartrending to see the inmates of one of these slave-sheds. They are huddled together like so many animals.

Notes

* Cover image of Morton Stanley with native boy not in the original magazine article.

Knowledge is Power in Our Struggle for Racial Survival

(Information that should be shared with as many of our people as possible — do your part to counter Jewish control of the mainstream media — pass it on and spread the word) … Val Koinen at KOINEN’S CORNER

PDF of this blog post. Click to view or download (1.7 MB).

The Slave Trade in the Congo Basin – Part 1

See also Part 2: The Slave Trade in the Congo Basin – Part 2 (last)

Version History

Version 3: Aug 3, 2020 — Improved formatting. Added images and PDF for katana17.com/wp/ version.

Version 2: Nov 27, 2017 — Improved formatting. Added link to Part 2.

Version 1: Published Feb 28, 2015

Pingback: The Slave Trade in the Congo Basin - Part 2 (last) - katana17katana17