[Hidden History is a revisionist book on how the jewish dominated (((Secret Elite))) engineered WWI, starting decades prior to it.

“The history of the First World War is a deliberately concocted lie. Not the sacrifice, the heroism, the horrendous waste of life or the misery that followed. No, these were very real, but the truth of how it all began and how it was unnecessarily and deliberately prolonged beyond 1915 has been successfully covered up for a century.”

Written by Gerry Docherty and Jim Macgregor, it’s:

“Dedicated to the victims of an unspeakable evil.“

— KATANA]

HIDDEN HISTORY

The Secret Origins

of the

First World War

Gerry Docherty and Jim Macgregor

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

Dedicated to the victims of an unspeakable evil.

Acknowledgements

FIRST AND FOREMOST WE OWE a debt to those writers and historians who, in the aftermath of the First World War, began to question what had happened and how it had come about. Their determination to challenge official accounts was largely dismissed by the Establishment, but they left a clear trail of credible evidence that has helped guide us through the morass of half-truths and lies that are still presented as historical fact. Without their cumulative effort, together with the profoundly important revelations of Professor Carroll Quigley, it would have been impossible for us to unpick the web of deceit woven around the origins of the war.

Special thanks are due to those who have encouraged our research over the years, made valuable suggestions and helped find sources to our enormous benefit. Will Podmore read our early chapters and offered sound advice. Guenter Jaschke has given us invaluable help in many ways, not least in providing and translating Austro-Hungarian and German political and military documents into English. Tom Cahill, American photojournalist and vibrant activist in the US Veterans against War movement, provided ongoing support, as did the American-Irish writer and political analyst Richard K. Moore. Other valued assistance came from Barbara Gunn in Ireland, Dr John O’Dowd in Glasgow and Brian Ovens, more locally.

We have to thank the ever-helpful librarians and researchers at the Scottish National Library in Edinburgh, both in the general reading rooms and the special documents section. We are grateful to the staff at the National Archives in Kew and the Bodleian Library, Oxford, especially in the special collections department, for their patience with us. Apologies are most certainly due to those we buttonholed and quizzed about missing documents, correspondence and papers at Oxford and Kew Gardens. As we were so correctly reminded, librarians and archivists can only provide access to the material that was passed into the library’s safekeeping by the Foreign or Cabinet Offices. What was removed, withdrawn, culled or otherwise destroyed, was effected many years ago by those empowered to do so.

The good advice of our literary agent, David Fletcher, and the enthusiasm of our superb editor, Ailsa Bathgate, is genuinely appreciated, though we may not have said so at the time. Thanks too are due to the other members of the wonderful team at Mainstream, including Graeme Blaikie for guiding us through the photographic content with consummate patience. Above all we thank Bill Campbell, who displayed great enthusiasm for the project.

Finally, tremendous gratitude is due to Maureen, Joan and our families, who have patiently supported us through the long years of research and writing. While we have often not been there for them, they have always been there for us.

July 2013

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 The Secret Society

CHAPTER 2 South Africa — Disregard the Screamers

CHAPTER 3 The Edward Conspiracy — First Steps and New Beginnings

CHAPTER 4 Testing Warmer Waters

CHAPTER 5 Taming the Bear

CHAPTER 6 The Changing of the Guard

CHAPTER 7 1906 — Landslide to Continuity

CHAPTER 8 Alexander Isvolsky — Hero and Villain

CHAPTER 9 Scams and Scandals

CHAPTER 10 Creating the Fear

CHAPTER 11 Preparing the Empire — Alfred Milner and the Round Table

CHAPTER 12 Catch a Rising Star and Put it in Your Pocket

CHAPTER 13 Moroccan Myths — Fez and Agadir

CHAPTER 14 Churchill and Haldane — Buying Time and Telling Lies

CHAPTER 15 The Roberts Academy

CHAPTER 16 Poincare — The Man Who Would be Bought

CHAPTER 17 America — A Very Special Relationship

CHAPTER 18 The Balkan Pressure Cooker — 1912-13

CHAPTER 19 From Balmoral to the Balkans

CHAPTER 20 Sarajevo — The Web of Culpability

CHAPTER 21 July 1914 — Deception, Manipulation and Misrepresentation

CHAPTER 22 July 1914 — Leading Europe Towards the Brink

CHAPTER 23 July 1914 — The First Mobilisations

CHAPTER 24 July 1914 — Buying Time — The Charade of Mediation

CHAPTER 25 Ireland — Plan B

CHAPTER 26 August 1914 — Of Neutrality and Just Causes

CHAPTER 27 The Speech That Cost a Million Dead

Conclusion — Lies, Myths and Stolen History

Appendix 1 — The Secret Elite’s Hidden Control and Connections, 1891-1914

Appendix 2 — Key Players

Notes

List of References

Index

Introduction

THE HISTORY OF THE FIRST World War is a deliberately concocted lie. Not the sacrifice, the heroism, the horrendous waste of life or the misery that followed. No, these were very real, but the truth of how it all began and how it was unnecessarily and deliberately prolonged beyond 1915 has been successfully covered up for a century. A carefully falsified history was created to conceal the fact that Britain, not Germany, was responsible for the war. Had the truth become widely known after 1918, the consequences for the British Establishment would have been cataclysmic.

At the end of the war Britain, France and the United States laid the blame squarely on Germany and took steps to remove, conceal or falsify documents and reports to justify such a verdict. In 1919, at Versailles near Paris, the victors decreed that Germany was solely responsible for the global catastrophe. She had, they claimed, deliberately planned the war and rejected all of their proposals for conciliation and mediation. Germany protested vehemently that she was not responsible and that it had been, for her, a defensive war against the aggression of Russia and France.

To the victors go the spoils, and their judgement was immediately reflected in the official accounts. What became the generally accepted history of the First World War revolved around German militarism, German expansionism, the kaiser’s bombastic nature and ambitions, and Germany’s invasion of innocent, neutral Belgium. The system of secret alliances, a ‘naval race’, economic imperialism, and the theory of an ‘inevitable war’ later softened the attack on Germany, though the spurious notion that she alone had wanted war remained understood in the background.

In the 1920s, a number of highly regarded American and Canadian professors of history, including Sidney B. Fay, Harry Elmer Barnes and John S. Ewart seriously questioned the Versailles verdict and the ‘evidence’ on which the assumption of German war guilt was based. Their work in revising the official Versailles findings was attacked by historians who insisted that Germany was indeed responsible. Today, eminent British war historians place the blame on Germany, though most are willing to concede that ‘other factors’ were also involved. Professor Niall Ferguson writes of the kaiser’s strategy of global war. [1] Professor Hew Strachan maintains that the war was about liberal countries struggling to defend their freedoms (against German aggression), [2] while Professor Norman Stone states that the greatest mistake of the twentieth century was made when Germany built a navy to attack Britain. [3] Professor David Stevenson quite unequivocally writes that ‘it is ultimately in Berlin that we must seek the keys to the destruction of peace’. [4] It was Germany’s fault. End of story.

Several other recent accounts on the causes of the war offer alternative ideas. Christopher Clark’s book, for example, looks on the events leading up to August 1914 as a tragedy into which an unsuspecting world ‘sleepwalked’. [5] We reveal that far from sleepwalking into a global tragedy, the unsuspecting world was ambushed by a secret cabal of warmongers in London. In Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War, we debunk the notion that Germany was to blame for this heinous crime against humanity, or that Belgium was an innocent, neutral nation caught unawares by German militarism. We clearly demonstrate that the German invasion of Belgium was not an act of thoughtless and indiscriminate aggression, but a reaction forced upon Germany when she faced imminent annihilation. From the day of its conception, the Schlieffen Plan [6] was a defence strategy and the last desperate act open to Germany to protect herself from being overrun simultaneously from east and west by the huge Russian and French armies massing on her borders.

What this book sets out to prove is that unscrupulous men, whose roots and origins were in Britain, sought a war to crush Germany and orchestrated events in order to bring this about. 1914 is generally considered as the starting point for the disaster that followed, but the crucial decisions that led to war had been taken many years before.

A secret society of rich and powerful men was established in London in 1891 with the long-term aim of taking control of the entire world. These individuals. whom we call the Secret Elite, deliberately fomented the Boer War of 1899-1902 in order to grab the Transvaal’s gold mines. and this became a template for their future actions. Their ambition overrode humanity, and the consequences of their actions have been minimised, ignored or denied in official histories. The horror of the British concentration camps in South Africa, where 20,000 children died, is conveniently glossed over; the devastating loss of a generation in a world war for which these men were deliberately responsible has been glorified by the lie that they died for ‘freedom and civilisation’. This book focuses on how a cabal of international bankers, industrialists and their political agents successfully used war to destroy the Boer Republics and then Germany, and were never called to account.

Carefully falsified history? A secret society taking control of the world? Britain responsible for the First World War? Twenty thousand children dying in British concentration camps? A cabal based in London whose prime objective was to destroy Germany? Lest any readers jump immediately to the conclusion that this book is some madcap conspiracy theory, they should, amongst other evidence, consider the work of Carroll Quigley, one of the twentieth century’s most highly respected historians.

Professor Quigley’s greatest contribution to our understanding of modern history was presented in his books, The Anglo-American Establishment and Tragedy and Hope. The former was written in 1949 but only released after his death in 1981. His disclosures placed him in such potential danger from an Establishment backlash that it was never published in his lifetime. In a 1974 radio broadcast, Quigley warned the interviewer, Rudy Maxa of the Washington Post, that ‘You better be discreet. You have to protect my future, as well as your own.’ [7]

The Anglo-American Establishment contained explosive details of how a secret society of international bankers and other powerful, unelected men controlled the levers of power and finance in Great Britain and the United States of America, and had done so throughout the twentieth century. Quigley’s evidence is considered highly credible. He moved in exalted circles, lectured at the top universities in the United States, including Harvard, Princeton and Georgetown, and was a trusted advisor to the Establishment as a consultant to the US Department of Defense. He gained access to evidence from people directly involved with the secret cabal that no outsider had ever seen. Though some of the facts came to him from sources which he was not permitted to name, he presented only those where he was ‘able to produce documentary evidence available to everyone’. [8]

Quigley noted a strong link between the highest echelons of power and influence in British government circles and Oxford University, particularly All Souls and Balliol colleges. He received a certain amount of assistance of a ‘personal nature’ from individuals close to what he called the ‘Group’, though ‘for obvious reasons’ he could not reveal the names of such persons. [9] Though sworn to secrecy, Quigley revealed in the radio interview that Professor Alfred Zimmern, the British historian and political scientist, had confirmed the names of the main protagonists within the ‘Group’. Without a shadow of doubt, Zimmern himself was a close associate of those at the centre of real power in Britain. He knew most of the key figures personally and was a member of the secret society for ten years before resigning in disgust in 1923.

Quigley noted that the ‘Group’ appeared oblivious to the consequences of their actions and acted in ignorance of the point of view of others. He described their tendency to give power and influence to individuals chosen through friendship rather than merit, and maintained that they had brought many of the things he held dear ‘close to disaster’. The great enigma of Professor Quigley lies in his statement that while he abhorred the cabal’s methods, he agreed with its goals and aims. [10] Were these merely words of self-preservation? Be mindful of his warning to Rudy Maxa as late as 1974. Quigley clearly felt that these revelations placed him in danger.

Through his investigations we know that Cecil Rhodes, the South African diamond millionaire, formed the secret society in London during the last decade of the nineteenth century. Its aims included renewal of the bond between Great Britain and the United States, and the spread of all they considered to be good in English ruling-class values and traditions. Their ultimate goal was to bring all habitable portions of the world under their influence and control. The individuals involved harboured a common fear, a deep and bitter fear, that unless something radical was done their wealth, power and influence would be eroded and overtaken by foreigners, foreign interests, foreign business, foreign customs and foreign laws. They believed that white men of Anglo-Saxon descent rightly sat at the top of a racial hierarchy, a hierarchy built on predominance in trade, industry and the exploitation of other races. To their minds, the choice was stark. Either take drastic steps to protect and further develop the British Empire or accept that countries like Germany would reduce them to bit-players on the world’s stage.

The members of this Secret Elite were only too well aware that Germany was rapidly beginning to overtake Britain in all areas of technology, science, industry and commerce. They also considered Germany to be a cuckoo in the Empire’s African nest and were concerned about its growing influence in Turkey, the Balkans and the Middle East. They set out to ditch the cuckoo.

The Secret Elite were influenced by the philosophy of the nineteenth-century Oxford professor John Ruskin, whose concept was built on his belief in the superiority and the authority of the English ruling classes acting in the best interests of their inferiors. And they professed that what they intended was for the good of mankind — for civilisation. A civilisation they would control, approve, manage and make profitable. For that, they were prepared to do what was necessary. They would make war for civilisation, slaughter millions in the name of civilisation. Wrapped in the great banner of civilisation, this became a secret society like no other before it. Not only did it have the backing of privilege and wealth but it was also protected from criticism and hidden beneath a shroud of altruism. They would take over the world for its own good. Save the world from itself.

The secret society specifically infiltrated the two great organs of imperial government: the Foreign Office and the Colonial Office, and established their control over senior civil servants who dominated these domains. In addition, they took control of the departments and committees that would enable their ambitions: the War Office, the Committee of Imperial Defence and the highest echelons of the armed services. Party-political allegiance was not a given prerequisite; loyalty to the cause most certainly was.

Their tentacles spread out to Russia and France, the Balkans and South Africa, and their targets were agents in the highest offices of foreign governments who were bought and nurtured for future use. America offered a different challenge. Initially, the possibility of bringing the United Stales back into an expanded empire was discussed but, realistically, American economic growth and future potential soon rendered such an idea redundant. Instead, they expanded their powerbase to bring Anglophile Americans into the secret brotherhood, men who would go on to dominate the world through financial institutions and dependent governments.

What’s more, they had the power to control history, to turn history from enlightenment to deception. The Secret Elite dictated the writing and teaching of history, from the ivory towers of academia down to the smallest of schools. They carefully controlled the publication of official government papers, the selection of documents for inclusion in the official version of the history of the First World War, and refused access to any evidence that might betray their covert existence. Incriminating documents were burned, removed from official records, shredded, falsified or deliberately rewritten, so that what remained for genuine researchers and historians was carefully selected material. Carroll Quigley’s histories have themselves been subject to suppression. Unknown persons removed Tragedy and Hope from the bookstore shelves in America, and it was withdrawn from sale without any justification soon after its release. The book’s original plates were unaccountably destroyed by Quigley’s publisher, the Macmillan Company, who, for the next six years ‘lied, lied, lied’ to him and deliberately misled him into believing that it would be reprinted. [11] Why? What pressures obliged a major publishing house to take such extreme action? Quigley claimed that powerful people had suppressed the book because it exposed matters that they did not want known.

To this day, researchers are denied access to certain First World War documents because the Secret Elite had much to fear from the truth, as do those who have succeeded them. They ensure that we learn only those ‘facts’ that support their version of history. It is worse than deception. They were determined to wipe out all traces that led back to them. They have taken every possible step to ensure that it would remain exceedingly difficult to unmask their crimes. We aim to do exactly that.

Our analysis of the secret origins of the First World War uses Professor Quigley’s academic research as one of many foundation stones, but goes far deeper than his initial revelations. He stated that evidence about the cabal is not hard to find ‘if you know where to look’. [12] We have done that. Starting with the principal characters whom he identified (and the insider, Alfred Zimmern, confirmed), this book traces their actions, interlinked careers, rise to power and influence, and finally exposes their complicity in ambushing the world into war. Quigley admitted that it was difficult to know who was active inside the group at any given time, and from our own research we have added to his lists those whose involvement and actions mark them out as linked members or associates. Secret societies work hard at maintaining their anonymity, but the evidence we have uncovered brings us to the considered conclusion that in the era that led into the First World War, the Secret Elite comprised a wider membership than Quigley originally identified.

This book is not a fictional story conjured on a whim. Despite the desperate attempt to remove every trace of Secret Elite complicity, the detailed evidence we present, chapter by chapter, reveals a tragic trail of misinformation, deceit, secret double-dealings and lies that left the world devastated and bankrupt. This is conspiracy fact, not theory.

A great many characters appear in the narrative of this history and we have appended a list of key players for ready referral if required. The reader faces a tantalisingly difficult challenge. These immensely rich and powerful men acted behind the scenes, shielded by the innermost core of the Establishment, by a controlled media and by a carefully vetted history. The following chapters prove that the official versions of history, as taught for more than a century, are fatally flawed: soaked in lies and half-truths. Those lies have penetrated so deeply into the psyche that the reader’s first reaction might be to discount evidence because it is not what they learned in school or university, or challenges their every assumption. The Secret Elite and their agents still seek to control our understanding of what really happened, and why. We ask only that you accept this challenge and examine the evidence we lay before you. Let your open-mindedness be the judge.

CHAPTER 1

The Secret Society

One wintry afternoon in February 1891, three men were engaged in earnest conversation in London. From that conversation were to flow consequences of the greatest importance to the British Empire and to the world as a whole.

THE OPENING PASSAGE OF PROFESSOR Carroll Quigley’s book The Anglo-American Establishment may read like a John Le Carre thriller, but this is no spy fiction. The three staunch British imperialists who met that day, Cecil Rhodes, William Stead and Lord Esher, drew up a plan for the organisation of a secret society that would take over the control of foreign policy both in Britain and, later by extension, the United States of America: a secret society that aimed to renew the Anglo-Saxon bond between Great Britain and the United States, [l] spread all that they considered good in the English ruling-class traditions, and expand the British Empire’s influence in a world they believed they were destined to control.

It was the heyday of both Jack the Ripper and Queen Victoria. The latter, having confronted her anti-Semitic prejudices, began a personal friendship with a member of the Rothschild banking dynasty, which played such an important role in what was to follow, [2] the former allegedly murdered Mary Kelly, his fifth and possibly final victim, in London’s fog-bound Whitechapel slums. [3] These two unrelated events captured the extremities of life in that era of privilege and poverty: sumptuous excess for the few, and penniless vulnerability for the many. Despite appalling social conditions, Victorian England sat confidently at the pinnacle of international power, steeped as it was in the ‘magnificence’ of the British Empire, but could it stay there for ever? This was the driving question exercising much serious debate in the cigar-smoke-filled parlours of influence, and the plan agreed between these three men was essentially an affirmation that steps had to be taken to ensure that Britain maintained its dominant position in world affairs.

The conspirators were well-known public figures, but it should be noted from the outset that each was linked to infinitely greater wealth and influence. The plan laid on the table was relatively simple. A secret society would be formed and run by a small, close-knit clique. The leader was to be Cecil Rhodes. He and his accomplices constructed the secret organisation around concentric circles, with an inner core of trusted associates — ‘The Society of the Elect’ — who unquestionably knew that they were members of an exclusive cabal devoted to taking and holding power on a worldwide scale. [4] A second outer circle, larger and quite fluid in its membership, was to be called ‘The Association of Helpers’. At this level of involvement, members may or may not have been aware that they were either an integral part of or inadvertently being used by a secret society. Many on the outer edges of the group, idealists and honest politicians, may never have known that the real decisions were made by a ruthless clique about whom they had no knowledge. [5] Professor Quigley revealed that the organisation was able to ‘conceal its existence quite successfully, and many of its influential members, satisfied to possess the reality of power rather than the appearance of power, are unknown even to close students of British history’. [6] Secrecy was the cornerstone. No one outside the favoured few knew of the society’s existence. Members understood that the reality of power was much more important and effective than the appearance of power, because they belonged to a privileged class that knew how decisions were made, how governments were controlled and policy financed. They have been referred to obliquely in speeches and hooks as ‘the money power’, the ‘hidden power’ or ‘the men behind the curtain’. All of these labels are pertinent, but we have called them, collectively, the Secret Elite.

The meeting in February 1891 was not some chance encounter. Rhodes had been planning such a move for years, while Stead and Esher had been party to his ideas for some time. A year earlier, on 15 February 1890. Rhodes journeyed from South Africa to Lord Rothschild’s country estate to present his plan. Nathaniel Rothschild, together with Lord Esher and some other very senior members of the British Establishment, was present. Esher noted at the time; ‘Rhodes is a splendid enthusiast, but he looks upon men as machines … he has vast ideas … and [is], I suspect, quite unscrupulous as to the means he employs.’ [7] In truth, these were exactly the qualities needed to be an empire builder; unscrupulous and uncaring with vast ambition.

Cecil Rhodes had long talked about setting up a Jesuit-like secret society, pledged to take any action necessary to protect and promote the extension of the power of the British Empire. He sought to ‘bring the whole uncivilised world under British Rule, for the recovery of the United States, for the making of the Anglo-Saxon race but one empire’. [8] In essence, the plan was as simple as that. Just as the Jesuit Order had been formed to protect the pope and expand the Catholic Church, answerable only to its own superior general and nominally the pope, so the Secret Society was to protect and expand the British Empire, and remain answerable to its leader. The holy grail was control not of God’s kingdom on earth in the name of the Almighty but of the known world in the name of the mighty British Empire. Both of these societies sought a different kind of world domination but shared a similar sense of ruthless purpose.

By February 1891, the time had come to move from ideal to action, and the formation of the secret society was agreed. It held secret meetings but had no need for secret robes, secret handshakes or secret passwords, since its members knew each other intimately. [9] Each of these initial three architects brought different qualities and connections to the society. Rhodes was prime minister of Cape Colony and master and commander of a vast area of southern Africa that some were already beginning to call Rhodesia. He was held to be a statesman, answerable to the British Colonial Office in terms of his governance, but in reality was a land-grabbing opportunist whose fortune was based on the Kimberly diamond mines. His wealth had been underwritten by brutal native suppression [10] and the global mining interests of the House of Rothschild, [11] to whom he was also answerable.

Rhodes had spent time at Oxford University in the 1870s and was inspired by the philosophy of John Ruskin, the recently installed professor of fine arts. Ruskin appeared to champion all that was finest in the public-service ethic, in the traditions of education, decency, duty and self-discipline, which he believed should be spread to the masses across the English-speaking world. But behind such well-serving words lay a philosophy that strongly opposed the emancipation of women, had no time for democracy and supported the ‘just’ war. [12] He advocated that the control of the state should be restricted to a small ruling class. Social order was to be built upon the authority of superiors, imposing upon inferiors an absolute, unquestioning obedience. He was repelled by what he regarded as the logical conclusion of Liberalism: the levelling of distinctions between class and class, man and man, and the disintegration of the ‘rightful’ authority of the ruling class. [13] As they sat listening to him, those future members of the secret society, Esher and Rhodes, must have thought they were being gifted a philosophical licence to take over the world. Cecil Rhodes drank from this fountain of dutiful influence and translated it into his dream to bring the whole uncivilised world under British rule. [14]

Rhodes entered South African politics to further his own personal ambitions, allied, of course, to the interests of the highly profitable mining industry. Although he paid reverent service to Ruskin’s philosophy, his actions betrayed a more practical, ruthless spirit. His approach to native affairs was brutal. In 1890, he instructed the House of Assembly in Cape Town that ‘the native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise. We must adapt a system of despotism, such as works so well in India, in our relations with the barbarians of South Africa.’ [15] The sense of superiority that he absorbed in his time at Oxford was expressed in plundering native reserves, clearing vast acres of ancestral tribal lands to suit gold and diamond exploration, and manipulating politics and business to the benefit of himself and his backers. Though he associated all his life with men whose sole motive was avarice, his expressed purpose was to use his ill-gotten wealth to advance his great ideal that the British Empire should control the whole world. [16]

Before he died of heart failure at the age of 48, and well aware that his lifespan would be limited, Rhodes wrote several wills and added a number of codicils. By 1902, the named trustees of his will included Lord Nathaniel Rothschild, Lord Rosebery, Earl Grey, Alfred Beit, Leander Starr Jameson and Alfred Milner, all of whom, as we shall see, operated at the heart of the secret society. Rhodes believed that ‘insular England was quite insufficient to maintain or even to protect itself without the assistance of the Anglo-Saxon peoples beyond the seas of Europe’. [17] In the years to come, problems of insularity required to be solved and links with America strengthened. Implicit in his grand plan was a determination to make Oxford University the educational centre of the English-speaking world and provide top scholars, in particular from every state in America, with the finance to ‘rub shoulders with every kind of individual and class on absolutely equal terms’. Those fortunate men who were awarded a Rhodes Scholarship were selected by the trustees in the expectation that their time at Oxford would instil ‘the advantage to the colonies and to the United Kingdom of the retention of the unity of the Empire’. [18] Bob Hawke, prime minister of Australia, and Bill Clinton, president of the United States, can be counted amongst later Rhodes Scholars.

But this Empire-maker was much more than just a university benefactor. His friend William (W.T.) Stead commented immediately after Rhodes’ death that he was ‘the first of the new dynasty of money-kings which has been evolved in these later days as the real rulers of the modern world’. [19] Great financiers had often used their fortunes to control questions of peace and war, and of course influence politics for profit. Rhodes was fundamentally different. He turned the objective on its head and sought to amass great wealth into his secret society in order to achieve political ends: to buy governments and politicians, buy public opinion and the means to influence it. He intended that his wealth be used by the Secret Elite to expand their control of the world. Secretly.

William Stead, Rhodes’ close associate in the secret society, represented a new force in political influence: the power of affordable newspapers that spread their views to ever-increasing numbers of working men and women. Stead was the most prominent journalist of his day. He had dared to confront Victorian society with the scandal of child prostitution in an outspoken article in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1885.

The details from his graphic expose of child abuse in London brothels shocked Victorian society. The underworld of criminal abduction, entrapment and ‘sale’ of young girls from under-privileged backgrounds was detailed in a series of ‘infernal narratives’, as Stead himself described them. These painted a horrendous picture of padded cells where upper-class paedophiles safely conducted their evil practices on children. [20] London society was thrown into a state of moral panic, and, as a consequence, the government was forced to pass the Criminal Law Amendment Act. Stead and several of his enlightened associates, including Bramwell Booth of the Salvation Army, were later charged with abduction as a result of the methods used in the investigation. Although Booth was acquitted, Stead spent three months in prison. [21]

This is what earned Stead his place in Rhodes’ elite company. He could influence the general public. Having embarrassed the government into making an immediate change in the law, Stead proceeded to campaign for causes in which he passionately believed, including education and land reforms, and in later years his was one of the most powerful voices demanding greater spending on the navy. Stead hoped to foster better relations with English-speaking nations and improve and reform British imperial policy. [22] He was one of the first journalistic crusaders and built an impressive network of young journalists around his newspapers, who in turn promoted the Secret Elite’s ambitions throughout the Empire. [23] The third man present at the inaugural meeting of the secret society was Reginald Balliol Brett, better known as Lord Esher, a close advisor to three monarchs. Esher had even greater influence in the upper echelons of society. He represented the interests of the monarchy from Queen Victoria’s final years, through the exuberant excesses of King Edward VII, to the more sedate but pliable King George V. He was described as ‘the eminence grise who ran England with one hand while pursuing adolescent boys with the other’. [24] Esher wrote letters of advice to King Edward VII almost daily during his eight-year reign, [25] and through him the king was kept fully appraised of Secret Elite business. His precise role in British politics was difficult to grasp even for his contemporaries. He chaired important secret committees, was responsible for appointments to the Cabinet, the senior ranks of the diplomatic and civil services, voiced strong personal opinion on top army posts and exerted a power behind the throne far in excess of his constitutional position. His role of powerbroker on behalf of the Secret Elite was without equal.

Two others quickly drawn into the inner elect of the secret society were Lord Nathaniel Rothschild, the international merchant banker, and Alfred Milner, a relatively little known colonial administrator who brought order and sense to the financial chaos in Egypt. Both of these men represented different aspects of control and influence. The Rothschild dynasty epitomised ‘the money power’ to a degree with which no other could compete. Alfred Milner was a self-made man, a gifted academic who began his working life as an aspiring lawyer, turned to journalism and eventually emerged as an immensely powerful and successful powerbroker. In time, he led the ‘men behind the curtain’.

The Rothschild dynasty was all-powerful in British and world banking and they considered themselves the equals of royalty, [26] even to the extent of calling their London base ‘New Court’. Like the British royal family, their roots lay in Germany, and the Rothschilds were possibly the most authentic dynasty of them all. They practised endogamy as a means of preventing dispersal of their great wealth, marrying not just within their own faith but also within their own immediate family. Of 21 marriages of the descendants of Mayer Amschel Rothschild, the original family patriarch, no fewer than 15 were between cousins.

Wealth begets wealth, never more so when it can provide or deny funds to governments and dominate the financial market on a global scale. The Rothschilds were pre-eminent in this field. They manipulated politicians, befriended kings, emperors and influential aristocrats, and developed their own particular brand of operation. Even the Metropolitan Police ensured that the Rothschild carriages had right of way as they drove through the streets of London. [27] Biographers of the House of Rothschild record that men of influence and statesmen in almost every country of the world were in their pay. [28] Before long, most of the princes and kings of Europe fell within their influence. [29] This international dynasty was all but untouchable:

The House of Rothschild was immensely more powerful than any financial empire that had ever preceded it. It commanded vast wealth. It was international. It was independent. Royal governments were nervous of it because they could not control it. Popular movements hated it because it was not answerable to the people. Constitutionalists resented it because its influence was exercised behind the scenes — secretly. [30]

Its financial and commercial links stretched into Asia, the near and Far East, and the northern and southern states of America. They were the masters of investment, with major holdings in both primary and secondary industrial development. The Rothschilds understood how to use their wealth to anticipate and facilitate the next market opportunity, wherever it was. Their unrivalled resources were secured by the close family partnership that could call on agents placed throughout the world. They understood the worth of foreknowledge a generation ahead of every other competitor. The Rothschilds communicated regularly with each other, often several times a day, with secret codes and trusted, well-paid agents, so that their collective fingers were on the pulse of what was about to happen, especially in Europe. Governments and crowned heads so valued the Rothschilds’ fast communications, their network of couriers, agents and family associates, that they used them as an express postal service, which in itself gave the family access to even greater knowledge of secret dealings. [31] It is no exaggeration to say that in the nineteenth century, the House of Rothschild knew of events and proposals long before any government, business rival or newspaper.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Rothschild family banking, investment and commercial dealings read like a list of international coups. Entire railway networks across Europe and America were financed through Rothschild bonds; investments in ores, raw materials, gold and diamonds, rubies, the new discoveries of oil in Mexico, Burma, Baku and Romania were financed through their banking empire, as were several important armaments finns including Maxim-Nordenfeldt and Vickers. [32] All of the main branches of the Rothschild family, in London, Paris, Frankfurt, Naples and Vienna, were joined together in a unique partnership. Working in unison, the branches were able to pool costs, share risks and guarantee each other major profits.

The Rothschilds valued their anonymity and, with rare exceptions, operated their businesses behind the scenes. Thus their affairs have been cleverly veiled in secrecy through the years. [33] They used agents and affiliated banks not only in Europe but all over the world, including New York and St Petersburg. [34] Their traditional system of semi-autonomous agents remained unsurpassed. [35] They would rescue ailing banks or industrial conglomerates with large injections of cash, take control and use them as fronts. For example, when they saved the small, ailing M.M. Warburg Bank in Hamburg, their enormous financial clout enabled it to grow into one of the major banks in Germany that went on to play a significant part in funding the German war effort in the First World War. This capacity to appear to support one side while actively encouraging another became the trademark of their effectiveness.

Though they were outsiders in terms of social position at the start of the nineteenth century, by the end of that same epoch the Rothschilds’ wealth proved to be the key to open doors previously barred by the sectarian bigotry that regularly beset them because of their Jewish roots. The English branch, N.M. Rothschild & Co., headed by Lionel Rothschild, became the major force within the dynasty. He promoted the family interests by befriending Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, whose chronic shortage of money provided easy access to his patronage. The Rothschilds bought shares for Albert through an intermediary, and in 1850 Lionel ‘loaned’ Queen Victoria and her consort sufficient funds to purchase the lease on Balmoral Castle and its 10,000 acres. [36] Lionel was succeeded by his son Nathaniel, or Natty, who as head of the London House became by far the richest man in the world.

Governments also fell under the spell of their munificent money power. It was Baron Lionel who advanced Disraeli’s Liberal government £4,000,000 to buy the Suez Canal shares from the bankrupt Khedive of Egypt in 1875, an equivalent of £1,176,000,000 at today’s prices. [37] Disraeli wrote jubilantly to Queen Victoria: ‘You have it, Madam … there was only one firm that could do it — Rothschilds. They behaved admirably; advanced the money at a low rate, and the entire interest of the Khedive is now yours.’ [38] The British government repaid the loan in full within three months to great mutual advantage.

The inevitable progress of the London Rothschilds toward the pinnacle of British society was reflected in Natty’s elevation to the peerage in 1885, by which time both he and the family had become an integral part of the Prince of Wales’ social entourage. Encouraged by their ‘generosity’, the prince lived well beyond his allowance from the Civil List, and Natty and his brothers, Alfred and Leo, maintained the family tradition of gifting loans to royalty. Indeed, from the mid 1870s onwards they covered the heir to the throne’s massive gambling debts and ensured that he was accustomed to a standard of luxury well beyond his means. Their ‘gift’ of the £160,000 mortgage (approximately £11.8 million today) for Sandringham ‘was discreetly hushed up’. [39] Thus both the great estates of Balmoral and Sandringham, so intimately associated with the British royal family, were facilitated, if not entirely paid for, through the largess of the House of Rothschild.

The Rothschilds frequently bankrolled pliant politicians. When he was secretary of state for India, Randolph Churchill (Winston’s father) approved the annexation of Burma on 1 January 1886, thus allowing the Rothschilds to issue their immensely successful shareholding in the Burma ruby mines. Churchill demanded that the viceroy, Lord Dufferin, annex Burma as a New Year’s present for Queen Victoria, but the financial gains rolled into the House of Rothschild. Esher noted sarcastically that Churchill and Rothschild seemed to conduct the business of the Empire together, and Churchill’s ‘excessive intimacy’, [40] with the Rothschilds caused bitter comment, but no one took them to task. On his death from syphilis, it transpired that Randolph owed an astonishing £66,902 to Rothschild, a vast debt that equates to a current value of around £5.5 million.

Although he was by nature and breeding a Conservative in terms of party politics, Natty Rothschild believed that on matters of finance and diplomacy all sides should heed the Rothschilds. He drew into his circle of friends and acquaintances many important men who, on the face of it, were political enemies. In the close world of politics, the Rothschilds exercised immense influence within the leadership of both Liberal and Conservative parties. They lunched with them at New Court, dined at exclusive clubs and invited all of the key policy makers to the family mansions, where politicians and royalty alike were wined and dined with fabulous excess. Collectively they owned great houses in Piccadilly in London, mansions in Gunnersby Park and Acton, Aylesbury, Tring, Waddeston Manor and Mentmore Towers (which became Lord Rosebery’s property when he married Hannah de Rothschild). Edward VII was always welcome at the sumptuous chateaux at Ferrieres or Alfred de Rothschild’s enormous town house when enjoying a weekend at the Parisian brothels. It was in such exclusive, absolutely private environments that the Secret Elite discussed their plans and ambitions for the future of the world, and, according to Niall Ferguson, the Rothschild biographer: ‘it was in this milieu that many of the most important political decisions of the period were taken’. [41]

The Rothschilds had amassed such wealth that nothing or no one remained outwith the purchasing power of their coin. Through it, they offered a facility for men to pursue great political ambition and profit. Controlling politics from behind the curtain, they avoided being held publicly responsible if or when things went wrong. They influenced appointments to high office and had almost daily communication with the great decision makers. [42] Dorothy Pinto, who married into the Rothschild dynasty, presented a tantalising glimpse of their familiarity with the centres of political power. Pinto recalled: ‘As a child I thought Lord Rothschild lived at the Foreign Office, because from my classroom window I used to watch his carriage standing outside every afternoon — while of course he was closeted with Arthur Balfour.’ [43] Foreign Secretary Balfour was a member of the inner circle of the secret society and destined to become prime minister.

Before he died in 1915, Natty ordered his private correspondence to be destroyed posthumously, denuding the Rothschilds’ archives of rich material and leaving the historian ‘to wonder how much of the House of Rothschild’s political role remains irrevocably hidden from posterity’. [44] Just what would have been revealed in these letters to and from prime ministers, foreign secretaries, viceroys, Liberal leaders like Rosebery, Asquith and Haldane, to say nothing of the all-powerful Alfred Milner or top Conservatives like Salisbury, Balfour, and Esher, the king’s voice and ears in the secret society? Ample evidence still exists to prove that all of these key players frequented the Rothschild mansions, [45] so what did these volumes of correspondence contain? There was no limit to the valuable information that Rothschild agents provided for their masters in New Court, which was then fed to the Foreign Office and Downing Street. Given that members of the Secret Elite removed all possible traces linking them to Rothschild, what Natty Rothschild ordered was precisely what was required to keep their actions hidden from future generations.

And what of the fifth name, the dark horse, the man behind the curtain? Alfred Milner was a key figure within the Secret Elite. He was returning home on holiday from his post in Egypt when the inaugural meeting was held but was already fully cognisant of Rhodes’ proposal. On his arrival back in London he was immediately inducted into the Society of the Elect. Like Rhodes, he had attended Ruskin’s lectures at Oxford and was a devoted disciple. [46] Milner was a man who commanded as much loyalty and respect as any Jesuit superior general.

Born in Germany in 1854, Alfred Milner was a gifted academic, fluent in French and German. Having no source of independent wealth, he relied on scholarships to pay for his education at Oxford. There he met and befriended the future prime minister Herbert Asquith, with whom he stayed in regular contact for the rest of his life. Clever and calculating, but without the gift of oratory, as a fledgling lawyer Milner augmented his salary by writing journalistic articles for the Fortnightly Review and the Pall Mall Gazette. There he worked alongside William Stead, whose crusading journalism appealed to him and whose campaigns in support of greater unity amongst English-speaking nations fostered a deep interest in South Africa.

Milner’s fervour for the Empire and the direction it might take brought him into a very exclusive circle of Liberal politicians gathered around Lord Rosebery. In 1885, he was invited for the first time to Rosebery’s mansion at Mentmore. Within a year, Rosebery was foreign secretary and, under his patronage, Milner advanced his career in the Civil Service. As Chancellor George Goschen’s personal secretary at the Treasury, Milner was largely responsible for the 1887 budget. His abilities were admired and respected. He was offered the post of director general of accounts in Cairo and took it up at a time when the British government began to fully appreciate the strategic importance of Egypt and the Suez Canal. The Rothschilds handled Egyptian financial affairs in London and on that first home visit in April 1891, Milner dined with Lord Rothschild, [47]and other highly influential figures within the Secret Elite. This was precisely the period when the secret society was taking its first steps towards global influence, yet even at that stage Professor Quigley could identify Milner as the man who would drive forward the Secret Elite:

Rhodes wanted to create a worldwide secret group devoted to English ideals and to the Empire as the embodiment of these ideals, and such a group was created in the period after 1890 by Rhodes, Stead, and, above all, by Milner. [48]

It was always Milner.

Alfred Milner’s dynamic personality drew like-minded, ambitious men to his side. His impressive organisational skills blossomed when, from 1892 to 1896, he headed the largest department of government, the Board of Inland Revenue. Milner was regularly a weekend guest at the stately homes of Lords Rothschild, Salisbury and Rosebery, and was knighted for his services in 1895. The following year he was recommended to the king by Lord Esher as high commissioner in South Africa, a post he made his own.

Perhaps the most remarkable fact about Alfred (later Viscount) Milner is that few people have heard his name outside the parameters of the Boer War, yet he became the leading figure in the Secret Elite from around 1902 until 1925. Why do we know so little about this man? Why is his place in history virtually erased from the selected pages of so many official histories? Carroll Quigley noted in 1949 that all of the biographies on Milner’s career had been written by members of the Secret Elite and concealed more than they revealed. [49] In his view, this neglect of one of the most important figures of the twentieth century was part of a deliberate policy of secrecy. [50]

Alfred Milner, a self-made man and remarkably successful civil servant whose Oxford University connections were unrivalled, became absolutely powerful within the ranks of these otherwise privileged individuals. Rhodes and Milner were inextricably connected through events in South Africa. Cecil Rhodes chided William Stead for saying that he ‘would support Milner in any measure he may take, short of war’. Rhodes had no such reservations. He recognised in Alfred Milner the kind of steel that was required to pursue the dream of world domination: ‘I support Milner absolutely without reserve. If he says peace, I say peace; if he says war, I say war. Whatever happens, I say ditto to Milner.’ [51]Milner grew in time to be the most able of them all, to enjoy the privilege of patronage and power, a man to whom others turned for leadership and direction. If any individual emerges as the central force inside our narrative, it is Alfred Milner.

Taken together, the five principal players — Rhodes, Stead, Esher, Rothschild and Milner — represented a new force that was emerging inside British politics, but powerful old traditional aristocratic families that had long dominated Westminster, often in cahoots with the reigning monarch, were also deeply involved, and none more so than the Cecil family.

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, the patriarchal 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, ruled the Conservative Party at the latter end of the nineteenth century. He served as prime minister three times for a total of fourteen years, between 1885 and 1902 (longer than anyone else in recent history). He handed over the reins of government to his sister’s son, Arthur Balfour, when he retired as prime minister in July 1902, confident that his nephew would continue to pursue his policies. Lord Salisbury had four siblings, five sons and three daughters who were all linked and interlinked by marriage to individuals in the upper echelons of the English ruling class. Important government positions were given to relations, friends and wealthy supporters who proved their gratitude by ensuring that his views became policy in government, civil service and diplomatic circles. This extended ‘Cecil-Bloc’ was intricately linked to the Society of the Elect and Secret Elite ambitions throughout the first half of the twentieth century. [52]

The Liberal Party was similarly dominated by the Rosebery dynasty. Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl Rosebery, was twice secretary of state for foreign affairs and prime minister between 1894 and 1895. Salisbury and Rosebery, like so many of the English ruling class, were educated at Eton and Oxford University. Adversarial political viewpoints did not interfere with their involvement behind the scenes inside the Secret Elite.

Rosebery had an additional connection that placed his influence on an even higher plane. He had married the most eligible heiress of that time, Hannah de Rothschild, and was accepted into the most close-knit banking family in the world, and certainly the richest. According to Professor Quigley, Rosebery was probably not very active in the Society of the Elect but cooperated fully with its members. He had close personal relationships with them, including Esher, who was one of his most intimate friends. Rosebery also liked and admired Cecil Rhodes, who was often his guest. He made Rhodes a privy counsellor, and in return Rhodes made Rosebery a trustee of his will. [53] Patronage, aristocratic advantage, exclusive education, wealth: these were the qualifications necessary for acceptance in a society of the elite, particularly in its infancy. They met for secret meetings at private town houses and magnificent stately homes. These might he lavish weekend affairs or dinner in a private club. The Rothschilds’ residences at Tring Park and Piccadilly, the Rosebery mansion at Mentmore, and Marlborough House when it was the private residence of the Prince of Wales (until he became King Edward VII in 1901), were popular venues, while exclusive eating places like Grillion’s and the even more ancient The Club provided suitable London bases for their discussions and intrigues.

These then were the architects who provided the necessary prerequisites for the secret society to take root, expand and grow into the collective Secret Elite. Rhodes brought them together and regularly refined his will to ensure that they would have financial backing. Stead was there to influence public opinion, and Esher acted as the voice of the king. Salisbury and Rosebery provided the political networks, while Rothschild represented the international money power. Milner was the master manipulator, the iron-willed, assertive intellectual who offered that one essential factor: strong leadership. The heady mix of international finance, political manipulation and the control of government policy was at the heart of this small clique of determined men who set out to dominate the world.

What this privileged clique intended might well have remained hidden from public scrutiny had Professor Carroll Quigley not unmasked it as the greatest influence in British political history in the twentieth century. The ultimate goal was to bring all habitable portions of the world under their control. Everything they touched was about control: of people and how their thoughts could be influenced; of political parties, no matter who was nominally in office. The world’s most important and powerful leaders in finance and business were part and parcel of this secret world, as would be the control of history: how it was written and how information would be made available. All of this had to be accomplished in secret — unofficially, with an absolute minimum of written evidence, which is, as you will see, why so many official records have been destroyed, removed or remain closed to public examination, even in an era of ‘freedom of information’.

CHAPTER 2

South Africa — Disregard the Screamers

CECIL RHODES THE SON OF an English vicar, left home as a 17 year old in 1870 to join his brother Herbert growing cotton on a farm in South Africa. The crop failed, but the brothers found work at the recently opened diamond fields of Kimberley. [1] Rhodes attracted the attention of the Rothschild agent Albert Gansi, who was assessing the local prospects for investment in diamonds. Backed by Rothschild funding, Cecil Rhodes bought out many small mining concerns, rapidly gained monopoly control and became intrinsically linked to the powerful House of Rothschild. [2] Although Rhodes was credited with transforming the De Beers Consolidated Mines into the world’s biggest diamond supplier, his success was largely due to the financial backing of Lord Natty Rothschild, who held more shares in the company than Rhodes himself. [3] Rothschild backed Rhodes not only in his mining ventures but on the issues of British race supremacy and expansion of the Empire. Neither had any qualms about the use of force against African tribes in their relentless drive to increase British dominance in Africa. It was a course of action destined to bring war with the Boer farmers of the Transvaal.

In 1877, by the age of 24, Cecil Rhodes had become a very rich young man whose life expectancy was threatened by ill health. In the first of his seven wills he stated that his legacy was to be used for:

The establishment, promotion and development of a Secret Society, the true aim and object whereof shall be for the extension of British rule throughout the world, the perfecting of a system of emigration from the United Kingdom, and of colonization by British subjects of all lands wherein the means of livelihood are attainable by energy, labour, and enterprise, and especially the occupation by British settlers of the entire continent of Africa … the whole of South America … the whole United States of America, as an integral part of the British Empire and, finally, the foundation of so great a Power as to render wars impossible, and promote the best interests of humanity. [4]

Rhodes’ will was a sham in terms of altruistic intent. Throughout his life, he consorted with businessmen driven by greed, [5] and did not hesitate to use bribery or force to attain his ends if he judged they would be effective. [6] Promotion of the ‘best interests of humanity’ was never evident in his lifestyle or business practices. Advised and backed by the powerful Rothschilds and his other inner-core Secret Elite friends, the Rand millionaires Alfred Beit and Sir Abe Bailey, [7] whose fortunes were also tied to gold and diamonds, Rhodes promoted their interests by gaining chartered company status for their investments in South Africa.

The British South Africa Company, created by Royal Charter in 1889, was empowered to form banks, to own, manage and grant or distribute land, and to raise a police force (the British South Africa Police). This was a private police force, owned and paid for by the company and its management. In return, the company promised to develop the territory it controlled, to respect existing African laws, to allow free trade within its territory and to respect all religions. Honeyed words, indeed. In practice, Rhodes set his sights on ever more mineral rights and territorial acquisitions from the African peoples by introducing laws with little concern or respect for tribal practices. The British had used identical tactics to dominate India through the East India Company a century earlier. Private armies, private police forces, the authority of the Crown and the blessing of investors was the route map to vast profits and the extension of the Empire. The impression that Rhodes and successors always sought to give, however, was that they did what had to be done, not for themselves but for the future of ‘humanity’. Imperialism has long been a flag of convenience.

The chartered company recruited its own army, as it was permitted to do, and, led by one of Cecil Rhodes’ closest friends, Dr Leander Starr Jameson, waged war on the Matabele tribes and drove them from their land. The stolen tribal kingdom, carved in blood for the profit of financiers, would later be named Rhodesia. It was the first time the British had used the Maxim gun in combat, slaughtering 3,000 tribesmen. [8]

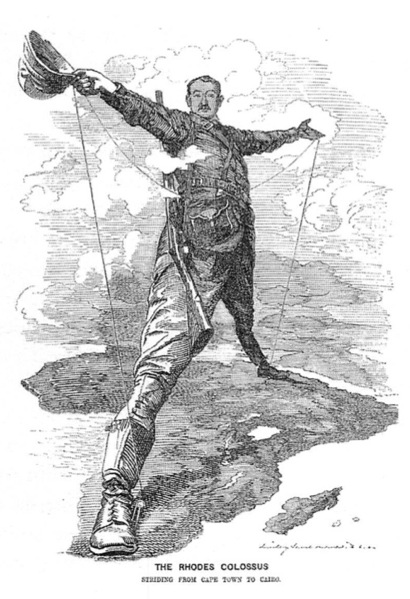

Leander Starr Jameson was born in Stranraer, Scotland. He trained as a doctor in London before emigrating to South Africa, where he became Rhodes’ physician and closest friend. Jameson was more responsible for the opening up of Rhodesia to British settlers than any other individual. His place in history’s hall of infamy was reserved not by the thousands of Matabele he slaughtered but by his abortive attempt to seize Boer territory in the Transvaal. To further his grand plans, Rhodes had himself elected to the legislature of Cape Colony and began extending British influence northward. His most ambitious design on the continent of Africa was a railway that would run from Cape Town to Cairo, which could effectively bring the entire landmass under British control. It would link Britain’s vast colonial possessions from the gold and diamond mines of South Africa to the Suez Canal, then on through the Middle East into India. It would similarly provide fast links from southern Africa through the Mediterranean to the Balkans and Russia, and through the Straits of Gibraltar to Britain. Every link in that chain would hold the Empire secure. Whoever was able to control this vast reach would control the world’s most valuable strategic raw materials, from gold to petroleum. [9]

1892 — Rhodes as Colossus, with telegraph line from Cape to Cairo. (Reproduced with permission of Punch Ltd., www.punch.co.uk)

In 1890, when Rhodes became prime minister of Cape Colony, his aggressive policies reignited old conflicts with the independent Boer Republics of Transvaal and the Orange River Colony. The Boers (farmers) were descendants of the Afrikaner colonists from northern mainland Europe, including Holland and Germany. Many Afrikaners remained under the British flag in Cape Colony, but in the 1830s and ‘40s others had made the famous ‘long trek’ (Die Groot Trek) with their cattle, covered wagons and Bibles into the African interior in search of farmland and escape from British rule. A number settled in lands to the north across the Orange River that would become the Boer republic of the Orange Free State. Others trekked on beyond the Vaal River into what became the Transvaal. Further north, across the Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers, lay the African kingdoms of the Matabele tribes.

Like the British settlers, many of the Calvinist Boers were racist, but, whatever their shortcomings, they were excellent colonisers with a moral code that was far better than that of the ‘money-grabbing, gold-seeking imperialist filibusters who were the friends of Cecil Rhodes’. [10] The British government had promised not to interfere in the self-governing Boer Republics, but that was prior to the discovery of massive gold deposits in the Transvaal in 1886. Prospects of untold wealth raised the stakes and created a new gold rush with a large influx of fortune- seeking prospectors from Britain). [11]

By the 1890s, the Boer Republics had become increasingly problematic for Rhodes. They did not fit easily into Secret Elite plans for a unified South Africa, nor his dream of the trans-African railway. The explosion of wealth in the Transvaal immediately transformed its importance. Political control lay in the hands of the rural, backward, Bible-bashing Boers, while economic control was increasingly in the hands of British immigrants sucked into the interior by the gold rush. These outsiders, or Uitlanders as the Boers termed them, had money but no political power. Despite the fact that Uitlander numbers in the Transvaal rapidly rose to twice that of the original Boer settlers, President Paul Kruger disbarred them from full citizenship until they had settled for a minimum of 14 years.

Kruger had left Cape Colony aged ten to trek northward with his family, and never outgrew his hatred and suspicion of the British. [12] His government placed heavy taxes on mining companies and made it almost impossible for the Uitlanders to acquire citizenship: two convenient reasons for the British to find fault. British-Boer conflict was all about the Transvaal’s gold. The Secret Elite wanted it and decided to take it by force. In December 1895, they planned to provoke an Uitlander uprising in Johannesburg as an excuse to seize the republic. Cecil Rhodes’ close friend Dr Jameson, the British South Africa Company’s military commander, simultaneously launched an armed raid from across the border to support the uprising. It was a hare-brained scheme cooked up by Rhodes and British-born Johannesburg business leaders, with the support of the British government. [13]

Alfred Beit and other members of the Secret Elite were deeply involved in planning, financing and arming the assault on the Transvaal. Months before it was due to take place, Rhodes disclosed his intentions to a close friend and member of the Secret Elite, Flora Shaw, the South African correspondent of The Times. [14] Shaw was a pioneering journalist in her own right and had worked closely with Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette. She was a personal friend of John Ruskin, who had encouraged her in her writings. [15] Thereafter, she wrote pro-Uitlander, anti-Boer articles in the London paper to prepare public opinion in England and grease the path to war. [16] Lord Albert Grey, yet another member of the inner core and a director of the British South Africa Company, sought official support for the uprising from Joseph Chamberlain, the colonial secretary in London. [17] Chamberlain was also given advance notice of the raid by the Liberal leader, Lord Rosebery. [18]

[Continued … ]

End of this sample Kindle book.

Enjoyed the preview?

Buy Now

or See details for this book in the Kindle Store

======================================

Click here for Hidden History Chpt 1 & 2

Click here for Hidden History – Amazon Reviews Part 1

Click here for Hidden History – Amazon Reviews Part 2

Click here for Hidden History – Amazon Reviews Part 3

PDF of this post.

Click to view or download (1.0MB). >> Hidden History Chpt 1 & 2

Knowledge is Power in Our Struggle for Racial Survival

(Information that should be shared with as many of our people as possible — do your part to counter Jewish control of the mainstream media — pass it on and spread the word) … Val Koinen

Version History

Version 3: Apr 28, 2020 — Re-uploaded images and PDF for katana17.com/wp/ version.

Version 2: Nov 12, 2014 — Added my introduction. Updated cover. Improved formatting.

Version 1: Published Sep 2, 2014.

Thanks for the good writeup. It in truth was once a amusement account it.

Look complex to more introduced agreeable from you!

By the way, how could we keep up a correspondence?

Reblogged this on The Stoker's Blog and commented:

Thanks K.

Thanks stoker for spreading the word!

Pingback: Updates — Plain List - katana17katana17

Pingback: That Blackguard — Winston Churchill - katana17katana17

Pingback: Hidden History: Amazon Customer Reviews - 1 - katana17katana17

Pingback: Hidden History: Amazon Customer Reviews - 3 - katana17katana17

Pingback: Das Blackguard — Winston Churchill - katana17katana17