Onward Christian Soldiers

[Part 12]

Note

This new version of Onward Christian Soldiers that I’ve compiled consists of the original contents published by Noontide Press in 1982 plus the “missing” text that, for reasons explained below, was in the Swedish version published in 1942.

I’ve also included some supplementary texts here giving the history of the missing parts of Day’s book. Also book reviews by Revilo Oliver and Amazon readers (see Part 1).

KATANA

Contents

Maps of Northern Europe & the Baltic States

THE REST OF DONALD DAY by Paul Knutson — 1984

EDITORIAL NOTE by Liberty Bell

The Resurrection of Donald Day — A review by Revilo P. Oliver. The Liberty Bell — January 1983

TWO KINDS OF COURAGE by Revilo P. Oliver. The Liberty Bell — October 1986

AMAZON REVIEWS

__________________

ONWARD CHRISTIAN SOLDIERS

Chapter

Introduction

Permit Me To Introduce Myself * (all new)

1 Why I did not go Home *………………………………. 1

2 The United States *………………………………………. 7

3 Latvia ………………………………………………………… 21

4 Meet the Bolsheviks *………………………………….. 41

5 Alliance with the Bear *……………………………….. 53

6 Poland ……………………………………………………….. 63

7 Trips ………………………………………………………….. 85

8 The Downfall of Democracy * ………………………. 93

9 Jews …………………………………………………………… 101

10 Russia *………………………………………………………. 115

11 Lithuania * ………………………………………………….. 131

12 Danzig ……………………………………………………….. 145

13 Estonia ……………………………………………………….. 151

14 Sweden ………………………………………………………. 159

15 Norway ………………………………………………………. 169

16 Finland ………………………………………………………. 183

17 England *……………………………………………………. 197

18 Europe *…………………………………………………….. 201

19 Epilogue *…………………………………………………… 204

Index of Names ………………………………………………….. 205

* Contains new material (dark blue text) missing from original Noontide edition.

MAP

of Northern Europe 1920s (click to enlarge in new window)

MAP

of Baltic States 1920s (click to enlarge in new window)

LIBERTY BELL PUBLICATIONS

June 1984

THE REST OF

DONALD DAY

by

Paul Knutson

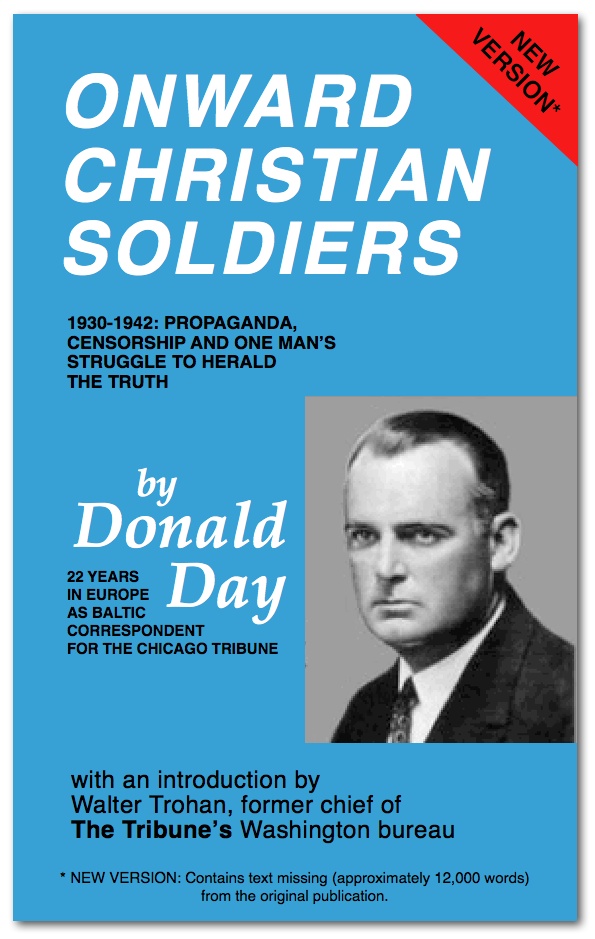

Donald Day, who had been for many years the foreign correspondent of the Chicago Tribune in northern Europe, wrote a record of his observations, Onward, Christian Soldiers, in 1942. His English text was first published as a book in 1982. It was printed by William Morrison and appeared under the imprint of the Noontide Press of Torrance, California, As Professor Oliver pointed out in his review of that book in Liberty Bell for January, 1983, the text had been copied, with some omissions and minor changes, from an anonymously issued mimeographed transcription of a defective carbon copy of the author’s manuscript, which had been brought to the United States in someway, despite the vigilance of Franklin Roosevelt’s surreptitious thought-police.

That was not the first publication of Day’s book. A Swedish translation, Framat Krististridsman, was published by Europa Edition in Stockholm in 1944. (That paper cover, printed in red, green, and black, is reproduced in black-and-white on the following page.)

Copies of this book still survive in Sweden and are even found in some public libraries. There may still be a copy in the Library of Congress, where, however, it was catalogued and buried among the very numerous books of a different Donald Day, a very prolific writer who midwifed the autobiography of Will Rogers and produced book after book on such various subjects as American humorists, the folk-lore of the Southwest, the tourist-attractions of Texas, and probably anything for which he saw a market, including a mendacious screed entitled Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Own Story. By a supreme irony, the Library concealed Framat Kristi stridsman in its catalogue by placing it between the other Day’s Evolution of Love and his propaganda piece for the unspeakably vile monster whose millions of victims included one of the last honest journalists.

The Swedish translation contains some long and important passages that do not appear in the book published in California and are not found in the mimeographed copy. By translating these back into English, I can restore Donald Day’s meaning, but, of course, I cannot hope to reproduce exactly the words and style of his original manuscript. I can also restore from the Swedish the deficiencies of the mimeographed transcript.

It seems impossible to determine now whether the parts of Day’s work that are preserved only in the Swedish were deleted by him to shorten his text when he sent a typewritten copy to the United States or were added by him before he turned his manuscript over to the Swedish translator at about the same time. At all events, the Swedish now alone provides us with some significant parts of bay‘s book and many Americans will want to have Day’s Work complete and entire.

For the convenience of the reader, I have, by arrangement with the publisher of Liberty Bell, included corrections of the printed English text where it departs, through negligence or misunderstanding, from the mimeographed text from which it was copied. I have passed over obvious typographical errors in the printed book, and omitted small and relatively unimportant corrections. For example, near the end of p. 44 of the printed book, the sentence should read, “All reported that the officials of the Cheka, later known as the GPU and NKVD, were Jews.”

Day did not use footnotes, so the reader will understand what all the footnotes [indicated by the symbol *] on the following pages are my own explanations of the text.

The supplements below are arranged in the order of pages of the printed book, as shown by the note in the small type that precedes each section, The three sources are discriminated typographically thus; Italics show what is copied from the printed text to give continuity.

Ordinary Roman type is used for what is in the mimeographed copy but was omitted from the printed version. This, of course, is precisely what Day wrote in English.

What I have translated back from the Swedish appears in this style of type. These passages, as I have said, convey Day’s meaning without necessarily restoring exactly the words he used in his English original, from which the Swedish version was made.

*****

Editorial Note

Liberty Bell

With the foregoing supplements, we have at last as accurate a text of Donald Day’s Onward, Christian Soldiers as we are likely to have, barring the remote possibility that the manuscript Day gave to his Swedish translator may yet be discovered.

The Swedish translation is pedestrian, as indeed is Day’s English style, but a comparison of the Swedish with the extant parts of the English assures me of the translator’s general competence. In one passage, which we have only in the Swedish, in which Day reports his refusal to become a well-paid and dignified member of our Diplomatic Service with a “little Morgenthau” as an “adviser” to tell him what to do, the translator was evidently confused by the irony of some English phrase such as “executive for a Jew” and reversed Day’s obvious meaning;, this was corrected in the foregoing text.

The mimeographed version is evidently a transcription from Day’s carbon copy, with only such errors as only the most expert typists can entirely avoid. There is, however, one very odd error in the mimeographed version corresponding to our printed page 4 above; it reads “the Great Rocky mountains of the border of Tennessee and North Carolina.” That is geographically absurd, of course, and the Swedish (stora Rijkiga Bergen) shows that Day wrote “Great Smoky mountains,” as we have, printed above. It is probably only a coincidence that the Swedish word for “Smoky” could have suggested, to a person who knew no Swedish, the error made by the typist in California who copied Day’s carbon copy.

When Day relies on his recollection of what he was told years before, his memory is sometimes faulty, and we have naturally made no changes in what he wrote. He makes an obvious error on our page 4, where he says that the Cherokees were driven from their lands and moved to Indian Territory “toward the end of the last century.” Actually, the expulsion of the Cherokee Nation by an American army took place in 1838. The Cherokees, by the way, were the most nearly civilized of all the Indian tribes in the territory that is now the United States and Canada, and it is true that their expulsion from the lands that had been guaranteed to them by treaty inflicted great hardships on them: they lost most of their property, including their negro slaves, and large numbers of them perished as they were quite brutally herded from the Appalachians almost half way across the continent to what is now the southern border of Arkansas.

Ethnologists who have made intensive studies of the Indians of North America (e.g., Peter Farb) regard Sequoyah (Sequoia) as perhaps “the greatest intellect the Indians produced.” He was the son of a Cherokee woman by an unidentified white trader, and, growing up with the mother’s people, regarded himself as a Cherokee. He, however, was an exception to what Day says about half-breeds. Day may have been confused about the date of the expulsion because a few of the Cherokees succeeded in hiding from the perquisition in the wilds of the Great Smokies and were eventually given the small reservation they now occupy east of Bryson City in the toe of North Carolina. There was some agitation about them “near the end of the last century.”

The circumstances in which Day’s carbon copy was smuggled into the United States remain obscure. When the mimeographed transcription was made and first issued, it contained a prefatory page on which an anonymous writer said,

“It is my understanding that this book was published in; 1942, and then merely made an appearance at the book-sellers, when all copies were immediately withdrawn and destroyed without a single copy escaping the book-burners, I was also told that Mr. Day died shortly after this incident.”

The page was presumably withdrawn when its author learned that Day was still alive at that time and an exile in Helsinki, since the Jews who rule the United States would not permit him to return to his native land.

It is curious that the man who made the transcription, which did effectively preserve Day’s work for the future, and who was evidently a resident of California, had heard a somewhat less plausible version of the rumor that was current in Washington in 1943. (See the review by Professor Oliver in Liberty Bell, January 1983, p. 27). It is quite possible that the source of both rumors was an effort by the apparatus of the great War Criminal in the White House to prevent the publication of the Swedish translation, which, as Day tells us in the last item in our supplements, was delayed in the press for two years by a “paper shortage” and it is noteworthy that the paper for it was finally obtained in Finland, not Sweden,* Until the book was finally published in 1944, the enemies of mankind could have imagined that their pressures on Sweden had effectively prevented Day’s exposure of one phase of their activity from ever appearing in print.

[* Day’s book was published by Europa Edition in Stockholm, which, however, had to have the printing done by Mercators Tryckeri in Helsinki. Although copies of the Swedish book have been preserved, Day’s work would not now be generally known — and would be supposed lost by Americans who heard of it — if the anonymous gentleman in California had not issued his mimeographed transcription.]

_______________________

KATANA — The Liberty Bell article continues with a list of text to be added or amended to the Noontide edition. All these changes (indicated by the dark blue text) have been entered in this expanded version of Onward Christian Soldiers.

Word Totals for the Additional Text

Introduction – –

Permit Me To Introduce Myself – 5,738 (all new)

Chapter 1 – 23

Chapter 2 – 307

Chapter 3 – –

Chapter 4 – 653

Chapter 5 – 1,225

Chapter 6 – –

Chapter 7 – –

Chapter 8 – 408

Chapter 9 – –

Chapter 10 – 907

Chapter 11 – 6

Chapter 12 – –

Chapter 13 – –

Chapter 14 – –

Chapter 15 – –

Chapter 16 – –

Chapter 17 – 2,167

Chapter 18 – 1,179

Chapter 19 – 89

Total words in original = 85,311

Total additional words = 12,702

_______________

Total words in expanded version = 98,013

ONWARD

CHRISTIAN

SOLDIERS

1920-1942: Propaganda, Censorship

and One Man’s Struggle to Herald the Truth

Suppressed reports of a 20-year Chicago Tribune

correspondent in eastern Europe from 1921

Donald Day

With an introduction by Walter Trohan,

former chief of the Tribune’s Washington bureau

THE NOONTIDE PRESS

Chapter 12

Danzig

If frontiers make patriots then for many years Danzig had every reason to be considered the most patriotic city in the world. Its citizens detested its frontiers. The great majority lived for one purpose; they wanted to become Germans again. The Free City of Danzig did not want to be free.

[Image] Map showing The Free City of Danzig

To be a Danziger was to be something incomplete. It was better to be German. It was unthinkable to the inhabitants that they should become Poles.

It was not a question of names. For many years the Danzig press chief was a big, heavy set, square-headed man named Lubianski, slow of speech and difficult to approach. His favorite sport happened to be my own. He was a passionate fisherman and through this we became friends.

[Image] The free city of Danzig (called Gdansk in Polish).

During this period the representative of PAT, Polska Agencja Telgraficzno, was an equally tall, but slender and round-headed man named Sonnenterg. I once had them both to lunch and suggested they might exchange their names.

Between the Danzigers and Poles, as between other nationalities in northeastern Europe, the chief difference seemed to be more one of culture than one of race or blood. There are many square-heads and other northern characteristics among the Poles. The plains of Poland have been overrun for centuries with armies of many different nationalities and races. All have left their mark upon the faces and skulls of the inhabitants.

[Page 146]

For Danzig freedom proved a curse. For many years the city had to rely on the League of Nations for protection. The various high commissioners appointed there proved unable to promote the slightest feeling of friendship and interdependence between Danzig and Poland. Both were jealous of their rights. The Poles continually sought means to extract more and more concessions from the Danzigers in the hope they might eventually Polanize the city. For Warsaw, possession of Danzig meant a firmer control of Poland’s corridor to the Baltic Sea. Poland tried to starve Danzig into submission by spending many millions of dollars in the construction of a new seaport, only a few miles away, at Gdynia.

On one of my visits to Gdynia in 1937, Polish officials escorted me on an auto drive through the town. Godlovski, editor of the local newspaper, asked for my impressions. I suggested the city architect by taken out and shot. The sightseeing tour aroused a feeling of indignation. Here was formerly a tiny fishing village situated at the mouth of a small river. Here was an opportunity to plan and erect a garden city which might have been easily made into the most beautiful municipality in Poland. Instead, the streets were flanked by the same disgraceful type of archaic tenements one could see in Bialostok, Warsaw and Lodz. Instead of creating a dimple to adorn the face of their country the Poles had created a wart.

Besides representing many years of graft, incompetence and waste, Gdynia was also a perpetual headache for the Danzigers who were obliged to be content with Poland’s more bulky exports-which were less profitable to handle-while Gdynia took the cream of the Polish trade.

When America’s newly appointed ambassador to Poland, John Cudahy, arrived in Gdynia on a Polish liner he had boarded in Amsterdam, he told the Poles their new harbor reminded him of Gary, Indiana. It was fortunate that none of his audience had been in Gary, for it is anything but a beautiful town.

Once while visiting Danzig, I had occasion to visit Mr. Pappe, then Polish high commissioner, in the large building which accommodated Warsaw’s ambitious representation. After the porter had taken my coat, I asked to be shown to the washroom. One becomes accustomed to filthy latrines in Poland where more than 80% of the population have neither seen nor used a water closet in their lives. But to discover an equally dirty latrine adjoining the reception hall of the Polish high commissioner in the cultured city of Danzig was a shock.

[Page 147]

I tried to inject the subject as gently as possible into our conversation and asked the high commissioner if Poland still claimed that Danzig should belong to Poland. He seemed surprised and said yes. I suggested if this be the case then he should immediately give an order to clean up his water closet and put it in commission again. If the Polish government wishes seriously to maintain its claim to be competent to administer the needs of Danzig, I remarked, then it should know how to keep a water closet in proper order.

At first Mr. Pappe seemed undecided whether to become angry or to treat the matter as a joke. Being a diplomat he found a formula to meet the occasion. He called in the porter, gave him a severe scolding, apologized to me and we continued our discussion of the latest squabble which had arisen between the Free City and Warsaw.

On another occasion, in 1932, the Reich authorities in Danzig invited me to visit the Marienberg castle and view the point where the frontiers of the Free City join with those of east Prussia and Poland on the Vistula river. At the last moment I was asked if I had any objection if another person joined our party. There was none, of course, and we were joined by Professor White of Princeton University, U.S.A.

The Marienberg castle is one of the really great sights of northern Europe. Its reconstruction took a long period of years and an enormous amount of research work by specialists of all kinds. The Germans, more especially the Prussians, are very proud of it and it is an historical monument that will continue to attract visitors for centuries to come.

After touring the castle, we were taken by car to several points on the river. At each stop a uniformed man appeared carrying a staff surmounted by an iron plaque upon which was embossed some salient facts and dates pertaining to the creation of the Free City and the locality. Next we were brought to see the village of Frauenwerder, situated right on the frontier, with its empty houses falling to ruin, grass growing between the cobbles on the street and presenting a picture of utter desolation and despair.

[Image] Fortress Marienberg and the Old Bridge

That night we had a frugal but extremely pleasant supper with General Budding and talked about Danzig, the corridor and the future. The professor was tremendously impressed and came to my room to discuss the events of the day. To him the Danzig corridor problem, through this visit, had become one of Europe’s unsolved and acute crisis points.

My impression was somewhat different. I called his attention to how those minor officials and local guides whom we had met had recited their little explanation talks as though they had committed them to memory, how General Budding was obviously receiving guests like ourselves several times each week, how his home had been equipped like a modest, comfortable little hotel. All this indicated not only that in the course of a year hundreds of foreigners had been his guests and made this conducted tour, but it revealed the German government categorically rejected the existence of the Danzig Corridor and the Free City and its intentions to remedy someday the situation caused by the malignant idiots who had so mutilated Germany.

[Page 148]

The professor and I talked till late, for I knew Poland well enough to inform him that she was going to be divided for the fourth time. I had come to that conclusion on my first visit to Poland in 1922 when I voiced it in the presence of foreign officials. During my many visits to Poland in the intervening years, I had seen nothing to change this opinion but had seen and experienced much to confirm it.

To me Marienberg castle embodied the German vision of the peril and riches of the east. The fact that many tens of thousands of school children, youths and adults annually visited its magnificent battlements and halls during those years showed that the German people were instinctively aware of their great past. The great castle stands not only as a symbol of the past, but as a promise facing the future. The age of chivalry has come to life again in our day, and in Europe. The spirit which once dwelt within the red brick walls of Marienberg is again militant today. It is far afield and in the East it is again shattering the hordes of infidel barbarians, and many new knights are being created on the field of battle.

As one leans out of the castle windows, it is easy to picture the landscape of centuries ago when farms were smaller, the forests greater, the roads unpaved and narrow and, instead of the great levees protecting fertile farms from the raging freshlets of the mighty river which flows northwest into the Baltic, there were great swamps. Then the knights in armor, accompanied by squires and lackies, took many days of dangerous plodding to accomplish a journey which today we make in a few hours in a comfortable automobile. Generations have lived and died within these walls, and where are their graves? The castle is their monument and the prosperous farms and towns are their work. Far down the road there is a flash of metal, but where once rode a knight on horseback now rides a group of boys on bicycles. Everything about Marienberg reminds what the present owes to the past and the debt which carries towards the future.

Not so many miles away there is another great monument, Tannenberg. It is not so beautiful as the castle. It is grim and thought-provoking.

The great circular wall of red brick seems to say:

“We shall eternally guard our heritage.”

From that heritage has come faith in destiny. And through this faith Europe has been saved from defilement and destruction.

[Page 149]

In Danzig the foreigner is constantly being brought face to face with the past. For generations this was the wealthiest city on the Baltic sea. If the Danzigers had chosen the easier road of collaboration with Poland, a small group of the inhabitants would have prospered greatly in helping to handle Poland’s commerce. But the great majority would have had their standard of living dragged down to the misery and squalor which prevailed throughout Poland. The town would have quickly filled with Poles and Jews. The Germans would have had to migrate, just as the Germans had to migrate from Thorn, Bromberg, Posen and other towns in Western Poland.

Every Danziger knew this and despite the conflicting interests of the many political groups, they stood steadfast against Poland’s dream of expansion. The Danzigers managed to survive an economic and propaganda siege of twenty years duration. Their spiritual strength which formed the core of their resistance was founded on their German culture.

Bromberg and Thorn were only a few miles away in the corridor. They were a frightful example of what happened to a German community when it came under the rule of Poland.

Danzig’s lesson to Europe is one of patience, vigilance and endurance.

Victory came after twenty years to Danzig. The Danzigers deserved it.

Chapter 13

Estonia

Estonia did not have a president. Its highest post was the State’s Oldest, a title and office similar to that of president in other countries.

Konstantin Piats was the first and last man to be elected to this post. He also held it for various terms during Estonia’s twenty two years of national existence. Piats spent the greater part of his life in the service of his country. Like his colleague, Karl Ulmanis of Latvia, Piats did not acquire personal wealth.

Outside Tallin (Reval), just behind the Piritta bathing beach, Piats had a small farm. On my many trips to Estonia I visited him there several times. Seated in his garden, where he could proudly contemplate his new modem cow barn, we would sip his homemade black current wine and talk frankly, like old friends.

One afternoon he gave me a glimpse into his life philosophy.

When I bought this bit of land many years ago, it was nothing but a scrub forest and mostly swamp. Now it is a lovely little farm which can provide a living for a family. Much of the work here I have done with my own hands. As I sit here I am filled with contentment. No matter what may come in the future I think I have accomplished my life’s work and the creating of this farm is the thing which gives me most satisfaction. We are here for a purpose. And if we take a piece of God’s earth and make it more beautiful and more fruitful, I think we have done something good, something we have been put here to do. I am very happy that I can look forward to leaving a small bit of the earth more beautiful than it was when I found it.

[Image] Estonia and surrounding countries.

Piats’ countenance glowed as he spoke. The soul of the man looked through his face. That spark of the divine which has been given to all of us either to stunt, kill or cultivate, he had cherished and developed. Yes, Piats had made a small piece of the earth more beautiful. And he had also succeeded in maturing and beautifying his soul. We can live for ourselves alone and in varying degrees become self-seeking and ruthless. Or we can live also for others and help and sacrifice when need be. Piats was one of those men who leave the earth just a bit better than the earth he came to.

Perhaps this is a better way of judging whether a life has been really successful or not. Others will agree in my estimation that Piats was a successful man.

Piats had great hopes for the future of his country and like other leading Baltic statesmen he made continued peace a condition to this progress. Like most Estonians, Piats viewed the future optimistically. He and his government had great plans to develop the tremendous seams of rich oil shale which underlie a wide strip of land between Narva and Tallin. This shale is so heavy with oil that during the world depression period Estonia was able to use it as fuel for her locomotives and spare the import of coal. Asphalt and motor fuel could be extracted. Another valuable product was a fluid which could be used to effectively impregnate wood against decay, which proved even better than creosote in the treatment of railroad ties.

Piats told me his dream was to reduce taxation and believed this was approaching reality with the exploitation of the oil shale deposits. He was confident this store of natural wealth would make his country rich and prosperous.

In 1921, when I first saw it, Reval was another drab little city whose chief source of income in pre-world-war days was the Imperial Russian Baltic fleet which was stationed there. The city grew and flourished with the Estonian state. And the Estonians, who were famed as gardeners in old Russia, made Tallin one of the most beautiful and attractive cities on the Baltic Sea.

Like another nation around the Baltic, the Estonians did not need to be told to do things. They were not like the Slavs. In fact one of the greatest qualities in all these nations is personal initiative. That is seen best by traveling through the country year after year. Not only did the new farms gain an atmosphere of comfortable prosperity with maturity, but the small marketing centers and towns grew brighter with their modem dairies, mills, grain elevators, warehouses and cooperative buildings.

One noticed the first modem buildings to appear were the schools and the last were the comfortable little hotels. Children looked well cared for.

[Page 153]

People were well dressed and well fed. Everywhere one could see Estonia had justified her claim to be a free nation for she was continually improving the living and cultural standards of her people.

The northern part of Estonia is a plateau which breaks off with high chalk cliffs into the Finnish gulf. The soil is thin and the main crop is potatoes. This was the poorest region of the country until someone made the discovery that the Estonian potato, when used as seed in the Mediterranean countries, gave a tremendous crop. Grown in chalky soil the Estonian potato was immune to disease. As it quickly germinates in the warm southern climate the export of seed potatoes was growing quickly when the war arrived.

Tallin’s castle crowns a spur of this chalk plateau and the town is built on land which slopes into the sea. It is on this slope in the suburbs that the Estonians built a great stadium to hold their song festivals. These were unique events for some 20,000 singers dressed in national costumes would stand on the stadium and the great volume of their voices would roll up the slope over the heads of the one hundred thousand audience and crash against the heavens while the June sun dipped itself below the horizon for a couple of hours before beginning another day.

[Image] Tallin’s Toompea Castle reconstructed from an ancient Estonian stronghold and continually supplemented from the 12th century on.

Twenty thousand singers. All with voices moulded and trained by folk songs. Estonia and Latvia had more choirs in proportion to their inhabitants than any other country in the world. Kristian Barons managed to collect 250,000 Latvian folk songs before his death and 12,000 people marched in his funeral procession, seven miles from the church to the cemetery. An unusual tribute to an unusual accomplishment! Yes, there is one volume containing naughty songs, for it is a complete collection.

Twenty years was too short a time for the Estonian and Latvian song festivals to attain world renown. They were great events in northern Europe and they will be heard again. Today these countries have voluntarily put armies into the fields to battle Bolshevism. The Baltic States bear scars of savagery which England and the United States today prefer to ignore while they make common cause with that communist excrescence which befouls them.

Estonia had no illusions about obtaining help from abroad when her crisis came in 1939 and Foreign Minister Salter was authorized by his government to sign the infamous treaty proposed by Moscow, giving the Red Army bases in Estonia, there was no appeal for help abroad. No even to the Finns, the racial brothers of the Estonians across the Finnish gulf.

Professor Piip, several times Estonian foreign minister who succeeded Salter, told me in 1939 the Estonians knew that any appeal to Finland would only embarrass the Finns and draw them into a crisis which Estonia hoped Finland would be spared.

[Page 154]

Salter, who had been enticed to Moscow to pay a visit to the All Russian Agricultural Exhibition, was bullied and insulted by the Commissars in the Kremlin. Shadanov, Commissar of the Leningrad district, talked smugly of the Red Army overwhelming and wiping out the population of the Baltic States. Soviet generals, to whom Salter and the Estonian delegation were introduced, were very warlike and said they would like nothing better than to have the Estonians resist.

Estonian had only one alliance, a mutual defense pact signed with Latvia in 1923 and still in force. But this proved just another one of those platonic agreements with neither feeling nor resolve behind it. Estonia received her death sentence stoically. The great majority of the people refused to believe the Bolsheviks were still as villainous as they had been during the revolution, civil war and class war in Russia. They thought Russia was being ruled by the Russians and did not realize the Soviet government was nothing more than a sadistic Jewish satrapy. They hoped against hope that Estonia would be treated with the same consideration the Soviets were reported to have employed in the organization of the Mongolian Soviet Republic where, so Moscow alleged, there was no Communist party at all but instead a national government operating under the beneficent guidance of Russia.

Estonia, like Finland, Sweden and Denmark, further believed that since she had very few Jews in her country that she had no Jewish problem. Estonia treated the Jews exceptionally well. A Zionist delegate visiting Tallin informed the Estonians that their remarkable tolerance towards the Jews had resulted in Estonia’s name being inscribed into the Golden Book of Tel Aviv, the first 100% Jewish city in the modem world, which is in Palestine.

Two Jews showed the Estonians their mistake. One was Herman Gudkin, 25 years old, son of an Estonian senator who was educated in England and was serving as a noncommissioned officer in the Tallin artillery regiment. When the Red Army seized Estonia he obtained sick leave. The following day he presented himself at his regiment’s headquarters in the Estonian uniform with a red band around his arm. He demanded the officers haul down their flag and surrender their arms.

His demands were rejected and he returned a short time later with Soviet tanks and armored cars and forced the surrender of the regiment, arresting the officers and confining the troops to barracks. Later this order was countermanded and the officers released. They attempted to arrest Gudkin as a deserter but he was protected by the Red Army.

[Page 155]

The next morning Gudkin, accompanied by another Jew, Victor Fagin, an ex-clothing dealer of Dorpat, climbed to the top of Pike Herman, an old stone tower which rises from the ancient castle housing the Estonian parliament and took the Estonian flag from the staff and hoisted the red soviet flag. The same afternoon a procession of Jewish residents led by Godkin and Fagin carried this Estonian flag through Tallin’s streets to the front of the Soviet legation where they tore it to pieces. I reported these facts to The Tribune which published them on 4th, July 1940, after deleting the word “Jew” from my message.

Fifteen months later I returned to Tallin in the company of three Finnish, three German and three Italian correspondents. I found a city of 150,000 with its entire merchant class exterminated, its industries in ruins and the men who owned and operated them shot. Its stores boarded up and empty of goods. Its educated class decimated by mass deportations which separated husbands from wives and mothers from children.

One third of Tallin’s male inhabitants had been mobilized, regardless of age or occupation, and taken into Soviet Russia.

For twenty one years I had been visiting Tallin two or three times each year. I had made many friends and acquaintances. Searching for two days I managed to find two of them. All the rest were gone, executed or exiled.

Tallin was not so much a victim of the war between Germany and Russia as she was a victim of Bolshevism’s class war which is really a war of the east against the west.

And after all that happened it is not surprising that there are no Jews left in Estonia today.

One of the two friends who survived the Red Terror in Tallin is Alexander Schultz, born in Vilna, an officer of one of the guard regiments and who married one of the grand daughters of Count Pitte. Alexander edited a small Russian newspaper and in 1921 it was he who first introduced me to Piats. A year under the Red Terror had left Alexander a nervous wreck.

Each night he and his wife went to bed expecting a visit from the GPU.

They each had their little satchel packed with a few essentials. He was frequently called to the GPU headquarters in Tallin for examination, or rather, to be bullied and threatened. The GPU wanted him to write a series of articles for the Moscow Isvestia against the Greek Orthodox church in Estonia. Each time Alexander refused he was threatened.

Soviet occupation was for him, as it was for many others, literally hell on earth. Alexander was a Russian. He did not speak German and made no attempt to repatriate with the Estonian Baits to Germany.

[Page 156]

It was in Tallin that I attended my second putsch. During the first six years of her independence the Estonian government followed a liberal policy and did not declare the communist party illegal. In 1924 the government was forced to take action. A little more than 100 members of the communist party were arrested and on 11 November they were placed on trial in Tallin. I came from Riga to follow the proceedings and noticed the attitude of the prisoners was arrogant. One of them, who continually interrupted the court martial, was taken out and summarily shot. This cowed the remaining prisoners who were duly convicted of conspiring to overthrow the government by force and sentenced to various terms of imprisonment.

After the trial was over I telegraphed to The Tribune that I found the situation threatening and intended to remain for a time in Estonia. This cable was relayed back to the press of the Baltic States from the Paris edition of our newspaper and the largest Latvian dally, The Jaunakas Sinas, published a violent attack against me urging that I be expelled from Latvia for sending out such a tendentious story. (The Communist putsch occurred a few days later.)

On the night of the thirtieth of November Alexander Schultz and myself, together with our wives, had dinner in the Linden restaurant in Tallin. We remained late and at another table I saw a group of Estonian officers.

At five in the morning I was awakened by the hotel porter who told me to get up, that there was a revolution in the town. Half awake, I questioned him and he told me to listen out the window and I would be able to hear the shooting. I got dressed quickly and placing a gun in my pocket and tying a white handkerchief around my. arm I started towards the telegraph office. Underway I met the party of Estonian officers who had been celebrating in the restaurant. They were led by General Podder. I loaned one of them my gun.

General Podder was the first to enter the telegraph office. On the stairway was standing a man with a rifle who raised it and leveled it at the general. He was standing on the second flight of stairs and was at a left angle to us. General Podder then made one of the best shots I ever saw.

When he glimpsed the man aiming his gun he shot him over his left shoulder. The bullet hit the Red in the chin and penetrated up into his brain and he fell dead. I accompanied the officers when they went through the telegraph offices. They found five other reds there and shot them all dead. Two of them were busy sending messages to Russia asking for aid when they met death. There was nobody to send off my message and those on duty had been sent home by the putschists. We then proceeded to the railroad station where we arrived in time to participate in the charge of the cadets who bayonetted a number of communists and seized other prisoners. This group of fifty armed reds had “captured” the railroad station and had telephoned the minister of communications and summoned him to the station by reporting a serious wreck had occurred.

[Page 157]

When he got out of his car he was shot on the spot. The cadets surprised the putschists at the moment they were preparing to execute a number of Estonian officers who had arrived on an early train. These men were being forced to undress as the communists wanted to use their uniforms.

The communists had also captured the airfield and had broken into the residence of the president. The officer on guard had time to spring from the window and alarm the guard across the street who was able to arrive in time to save the president, M. Akel, from assassination. Some twenty policemen, soldiers and private citizens were murdered by the putschists before order was restored. Investigation revealed this plot had been organized and directed from Russia. Several hundred communists were smuggled in freighters from Soviet Russia into Estonia where they were met and led by other imported and local revolutionists. The Estonian authorities showed no mercy. Every one of the reds captured in the Tallin putsch was executed.

It was only after this attempt that the Estonian government followed the example of Latvia, Lithuania and Poland and passed a law making the communist party an illegal organization.

Together with their brothers, the Finns, the Estonians cultivated close ties with Sweden. As the smallest of the Baltic republics grew older and more prosperous more and more Swedes began to spend their summer vacations at Estonian resorts where modem hotels and casinos made their appearance. It took many years for Sweden to get interested in her little neighbors across the Baltic, but finally King Gustav paid Estonia and Latvia a visit. King Gustav is the only foreign visitor who has ever made a crowd of Latvians break into cheers. Sweden has great traditions in the Baltic and she has left memories of “good times” in Estonia and northern Latvia which she ruled from 1561 to 1710.

So let us visit a country exceptionally favored by geography, Sweden.

_______________________

NOTES

* Images (maps, photos, etc.) have also been added that were not part of the original Noontide edition.

__________________

Knowledge is Power in Our Struggle for Racial Survival

(Information that should be shared with as many of our people as possible — do your part to counter Jewish control of the mainstream media — pass it on and spread the word) … Val Koinen at KOINEN’S CORNER

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 1: Reviews; Background Information

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 2: Introduction; Permit Me to Introduce Myself

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 3: Why I Did Not Go Home; The U.S.

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 4: Lativa

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 5: Meet the Bolsheviks

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 6: Alliance With the Bear

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 7: Poland

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 8: Trips; The Downfall of Democracy

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 9: Jews

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 10: Russia

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 11: Lithuania

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 12: Danzig; Lithuania

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 13: Sweden; Norway

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 14: Finland

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 15 (last) : England; Europe; Epilogue; Index of Names

PDF of this blog post. Click to view or download (3.0 MB).

>>Onward Christian Soldiers by Donald Day – Part 12 Ver 2

Version History

Version 3: Dec 8, 2019 — Re-uploaded images and PDF for katana17.com/wp/ version

Version 2: Mar 28, 2015 – Added images.

Version 1: Published Mar 28, 2015

Pingback: Onward Christian Soldiers - Part 1: Reviews, Background Information - katana17katana17