Onward Christian Soldiers

[Part 5]

Note

This new version of Onward Christian Soldiers that I’ve compiled consists of the original contents published by Noontide Press in 1982 plus the “missing” text that, for reasons explained below, was in the Swedish version published in 1942.

I’ve also included some supplementary texts here giving the history of the missing parts of Day’s book. Also book reviews by Revilo Oliver and Amazon readers (see Part 1).

KATANA

Contents

Maps of Northern Europe & the Baltic States

THE REST OF DONALD DAY by Paul Knutson — 1984

EDITORIAL NOTE by Liberty Bell

The Resurrection of Donald Day — A review by Revilo P. Oliver. The Liberty Bell — January 1983

TWO KINDS OF COURAGE by Revilo P. Oliver. The Liberty Bell — October 1986

AMAZON REVIEWS

__________________

ONWARD CHRISTIAN SOLDIERS

Chapter

Introduction

Permit Me To Introduce Myself * (all new)

1 Why I did not go Home *………………………………. 1

2 The United States *………………………………………. 7

3 Latvia ………………………………………………………… 21

4 Meet the Bolsheviks *………………………………….. 41

5 Alliance with the Bear *……………………………….. 53

6 Poland ……………………………………………………….. 63

7 Trips ………………………………………………………….. 85

8 The Downfall of Democracy * ………………………. 93

9 Jews …………………………………………………………… 101

10 Russia *………………………………………………………. 115

11 Lithuania * ………………………………………………….. 131

12 Danzig ……………………………………………………….. 145

13 Estonia ……………………………………………………….. 151

14 Sweden ………………………………………………………. 159

15 Norway ………………………………………………………. 169

16 Finland ………………………………………………………. 183

17 England *……………………………………………………. 197

18 Europe *…………………………………………………….. 201

19 Epilogue *…………………………………………………… 204

Index of Names ………………………………………………….. 205

* Contains new material (dark blue text) missing from original Noontide edition.

MAP

of Northern Europe 1920s (click to enlarge in new window)

MAP

of Baltic States 1920s (click to enlarge in new window)

LIBERTY BELL PUBLICATIONS

June 1984

THE REST OF

DONALD DAY

by

Paul Knutson

Donald Day, who had been for many years the foreign correspondent of the Chicago Tribune in northern Europe, wrote a record of his observations, Onward, Christian Soldiers, in 1942. His English text was first published as a book in 1982. It was printed by William Morrison and appeared under the imprint of the Noontide Press of Torrance, California, As Professor Oliver pointed out in his review of that book in Liberty Bell for January, 1983, the text had been copied, with some omissions and minor changes, from an anonymously issued mimeographed transcription of a defective carbon copy of the author’s manuscript, which had been brought to the United States in someway, despite the vigilance of Franklin Roosevelt’s surreptitious thought-police.

That was not the first publication of Day’s book. A Swedish translation, Framat Krististridsman, was published by Europa Edition in Stockholm in 1944. (That paper cover, printed in red, green, and black, is reproduced in black-and-white on the following page.)

Copies of this book still survive in Sweden and are even found in some public libraries. There may still be a copy in the Library of Congress, where, however, it was catalogued and buried among the very numerous books of a different Donald Day, a very prolific writer who midwifed the autobiography of Will Rogers and produced book after book on such various subjects as American humorists, the folk-lore of the Southwest, the tourist-attractions of Texas, and probably anything for which he saw a market, including a mendacious screed entitled Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Own Story. By a supreme irony, the Library concealed Framat Kristi stridsman in its catalogue by placing it between the other Day’s Evolution of Love and his propaganda piece for the unspeakably vile monster whose millions of victims included one of the last honest journalists.

The Swedish translation contains some long and important passages that do not appear in the book published in California and are not found in the mimeographed copy. By translating these back into English, I can restore Donald Day’s meaning, but, of course, I cannot hope to reproduce exactly the words and style of his original manuscript. I can also restore from the Swedish the deficiencies of the mimeographed transcript.

It seems impossible to determine now whether the parts of Day’s work that are preserved only in the Swedish were deleted by him to shorten his text when he sent a typewritten copy to the United States or were added by him before he turned his manuscript over to the Swedish translator at about the same time. At all events, the Swedish now alone provides us with some significant parts of bay‘s book and many Americans will want to have Day’s Work complete and entire.

For the convenience of the reader, I have, by arrangement with the publisher of Liberty Bell, included corrections of the printed English text where it departs, through negligence or misunderstanding, from the mimeographed text from which it was copied. I have passed over obvious typographical errors in the printed book, and omitted small and relatively unimportant corrections. For example, near the end of p. 44 of the printed book, the sentence should read, “All reported that the officials of the Cheka, later known as the GPU and NKVD, were Jews.”

Day did not use footnotes, so the reader will understand what all the footnotes [indicated by the symbol *] on the following pages are my own explanations of the text.

The supplements below are arranged in the order of pages of the printed book, as shown by the note in the small type that precedes each section, The three sources are discriminated typographically thus; Italics show what is copied from the printed text to give continuity.

Ordinary Roman type is used for what is in the mimeographed copy but was omitted from the printed version. This, of course, is precisely what Day wrote in English.

What I have translated back from the Swedish appears in this style of type. These passages, as I have said, convey Day’s meaning without necessarily restoring exactly the words he used in his English original, from which the Swedish version was made.

*****

Editorial Note

Liberty Bell

With the foregoing supplements, we have at last as accurate a text of Donald Day’s Onward, Christian Soldiers as we are likely to have, barring the remote possibility that the manuscript Day gave to his Swedish translator may yet be discovered.

The Swedish translation is pedestrian, as indeed is Day’s English style, but a comparison of the Swedish with the extant parts of the English assures me of the translator’s general competence. In one passage, which we have only in the Swedish, in which Day reports his refusal to become a well-paid and dignified member of our Diplomatic Service with a “little Morgenthau” as an “adviser” to tell him what to do, the translator was evidently confused by the irony of some English phrase such as “executive for a Jew” and reversed Day’s obvious meaning;, this was corrected in the foregoing text.

The mimeographed version is evidently a transcription from Day’s carbon copy, with only such errors as only the most expert typists can entirely avoid. There is, however, one very odd error in the mimeographed version corresponding to our printed page 4 above; it reads “the Great Rocky mountains of the border of Tennessee and North Carolina.” That is geographically absurd, of course, and the Swedish (stora Rijkiga Bergen) shows that Day wrote “Great Smoky mountains,” as we have, printed above. It is probably only a coincidence that the Swedish word for “Smoky” could have suggested, to a person who knew no Swedish, the error made by the typist in California who copied Day’s carbon copy.

When Day relies on his recollection of what he was told years before, his memory is sometimes faulty, and we have naturally made no changes in what he wrote. He makes an obvious error on our page 4, where he says that the Cherokees were driven from their lands and moved to Indian Territory “toward the end of the last century.” Actually, the expulsion of the Cherokee Nation by an American army took place in 1838. The Cherokees, by the way, were the most nearly civilized of all the Indian tribes in the territory that is now the United States and Canada, and it is true that their expulsion from the lands that had been guaranteed to them by treaty inflicted great hardships on them: they lost most of their property, including their negro slaves, and large numbers of them perished as they were quite brutally herded from the Appalachians almost half way across the continent to what is now the southern border of Arkansas.

Ethnologists who have made intensive studies of the Indians of North America (e.g., Peter Farb) regard Sequoyah (Sequoia) as perhaps “the greatest intellect the Indians produced.” He was the son of a Cherokee woman by an unidentified white trader, and, growing up with the mother’s people, regarded himself as a Cherokee. He, however, was an exception to what Day says about half-breeds. Day may have been confused about the date of the expulsion because a few of the Cherokees succeeded in hiding from the perquisition in the wilds of the Great Smokies and were eventually given the small reservation they now occupy east of Bryson City in the toe of North Carolina. There was some agitation about them “near the end of the last century.”

The circumstances in which Day’s carbon copy was smuggled into the United States remain obscure. When the mimeographed transcription was made and first issued, it contained a prefatory page on which an anonymous writer said,

“It is my understanding that this book was published in; 1942, and then merely made an appearance at the book-sellers, when all copies were immediately withdrawn and destroyed without a single copy escaping the book-burners, I was also told that Mr. Day died shortly after this incident.”

The page was presumably withdrawn when its author learned that Day was still alive at that time and an exile in Helsinki, since the Jews who rule the United States would not permit him to return to his native land.

It is curious that the man who made the transcription, which did effectively preserve Day’s work for the future, and who was evidently a resident of California, had heard a somewhat less plausible version of the rumor that was current in Washington in 1943. (See the review by Professor Oliver in Liberty Bell, January 1983, p. 27). It is quite possible that the source of both rumors was an effort by the apparatus of the great War Criminal in the White House to prevent the publication of the Swedish translation, which, as Day tells us in the last item in our supplements, was delayed in the press for two years by a “paper shortage” and it is noteworthy that the paper for it was finally obtained in Finland, not Sweden,* Until the book was finally published in 1944, the enemies of mankind could have imagined that their pressures on Sweden had effectively prevented Day’s exposure of one phase of their activity from ever appearing in print.

[* Day’s book was published by Europa Edition in Stockholm, which, however, had to have the printing done by Mercators Tryckeri in Helsinki. Although copies of the Swedish book have been preserved, Day’s work would not now be generally known — and would be supposed lost by Americans who heard of it — if the anonymous gentleman in California had not issued his mimeographed transcription.]

_______________________

KATANA — The Liberty Bell article continues with a list of text to be added or amended to the Noontide edition. All these changes (indicated by the dark blue text) have been entered in this expanded version of Onward Christian Soldiers.

Word Totals for the Additional Text

Introduction – –

Permit Me To Introduce Myself – 5,738 (all new)

Chapter 1 – 23

Chapter 2 – 307

Chapter 3 – –

Chapter 4 – 653

Chapter 5 – 1,225

Chapter 6 – –

Chapter 7 – –

Chapter 8 – 408

Chapter 9 – –

Chapter 10 – 907

Chapter 11 – 6

Chapter 12 – –

Chapter 13 – –

Chapter 14 – –

Chapter 15 – –

Chapter 16 – –

Chapter 17 – 2,167

Chapter 18 – 1,179

Chapter 19 – 89

Total words in original = 85,311

Total additional words = 12,702

_______________

Total words in expanded version = 98,013

ONWARD

CHRISTIAN

SOLDIERS

1920-1942: Propaganda, Censorship

and One Man’s Struggle to Herald the Truth

Suppressed reports of a 20-year Chicago Tribune

correspondent in eastern Europe from 1921

Donald Day

With an introduction by Walter Trohan,

former chief of the Tribune’s Washington bureau

THE NOONTIDE PRESS

Chapter 4

I Meet the Bolsheviks

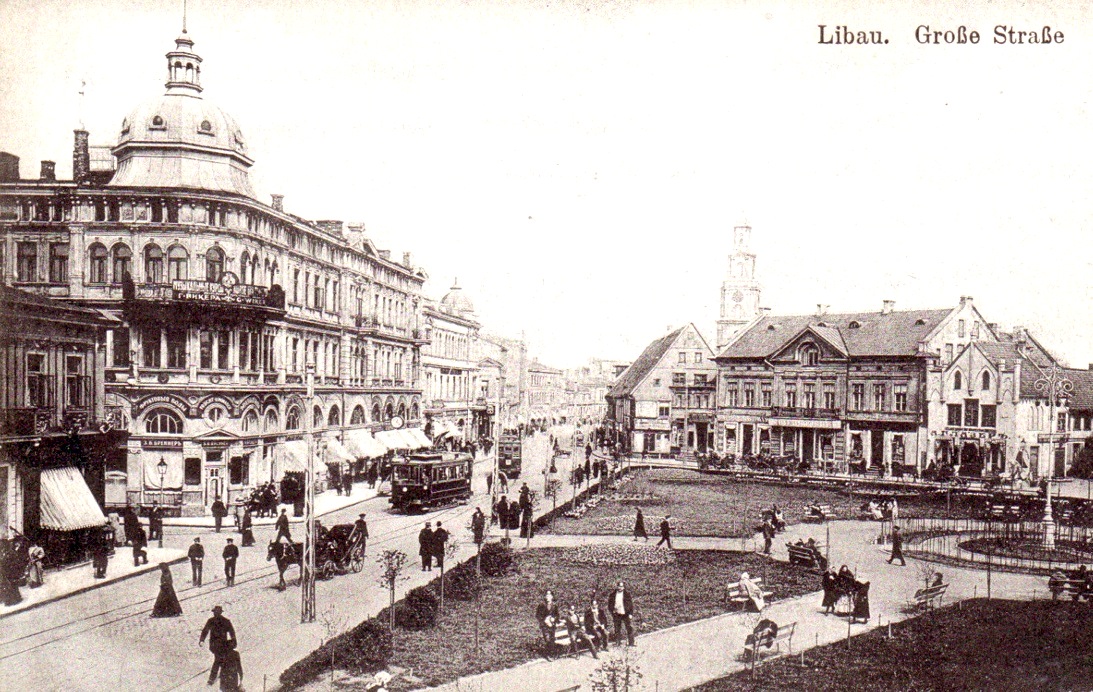

I arrived in Libau on a January morning in 1921. The ship was moored on the quay next to the gates of the customs yard where, on a barrier of barbed wire, some twenty small children were clinging and crying for bread. Our steamer was the only ship in the harbor. The sailors gave each of the children a big hunk of bread and from the way they devoured it one could see they were really hungry.

[Image] Libau on the coast of Latvia.

I had encountered hunger before in American mining villages where miners had been on strike for many weeks and the strikers allowances from the union had been reduced to almost nothing. In Latvia I encountered hunger which affected a nation. The American Red Cross and the American Relief Administration were feeding tens of thousands of children in the Baltic States and Poland every day.

In Libau the entire St. Petersburg hotel had been taken over by the Soviet consulate. There were more than 100 people on the staff. With the exception of the consul and a few assistants they were all New York Jews.

Naturally the consul and these assistants were also Jews, but of Russian nationality.

Ali Baba and his forty thieves were rank amateurs compared to the staff of the Labau Soviet consulate. They considered it their duty to relieve all persons repatriating to Russia of their money and other valuables. The possession of a gold watch was considered counter-revolutionary, most of these deluded people who were entering Russia to participate in the pleasures of the Soviet paradise were Russians and Ukrainians. There were also many groups of revolutionary inclined Latvians, Lithuanians, Poles and Finns.

[Page 42]

On the walls of the consulate hung large signs in many languages announcing it was strictly forbidden to bring foreign currency of any kind into Russia and that it must be turned over to the consulate at the rate of 11,000 roubles for $1. Before being permitted to proceed further on their journey each immigrant was interviewed by a member of the consulate who informed him that if they had concealed currency or other valuables they had better surrender them immediately to avoid serious trouble.

I watched many of these interviews. The largest sum I saw turned over to the consulate officials was eleven thousand dollars in bills. This man was a carpenter-contractor who had lived 24 years in the United States and who had sold his home in order to migrate to Russia. Many thousands of such people passed through Libau en-route to Russia and almost certain starvation. The consulate officials would not reveal to me the total amount of confiscated foreign currency, but it was a large sum. On one occasion I was shown a large envelope containing the former belongings of a group of 120 such immigrants and was told it contained more than one hundred thousand dollars in cash.

The consulate found it impossible to provide sufficient roubles for all the money they exchanged. So for all sums above fifty dollars they gave a check on a Moscow bank. This bank had been nationalized and closed. It no longer existed. The victims of this swindle frequently made violent protests when they arrived in Moscow. Many were arrested and disappeared into numerous concentration camps, the living cemeteries of the better class people in Russia.

[Image] Postcard of Libau in the 1920s

The streets of Libau swarmed with more Jews seeking contact with the well-dressed prosperous immigrants. They offered them 80,000 roubles for $1. These swindlers also obtained their roubles from their friends in the Soviet consulate. This wholesale swindling went on for another year and I think my articles had something to do with the closing down of the Bolshevik Kosher Consulate in Libau.

I was much surprised to find nothing but New York and Russian Jews in the consulate and wondered when I would meet a real Russian Soviet employee. There was no sleeping car on the train to Riga so I sat up all night. Riga was just a depressing a sight as Libau. Streets were lined with shops whose boarded windows told of a famine of all kinds of goods.

On Kald street, the main thoroughfare through the old town, I found a bakery, the only one in the city, selling sweet cakes and tea.

[Page 43]

Visiting the Soviet legation, I filled out the long questionnaire applying or a Soviet visa. The official was a Whitechapel Jew from London who told me his name there had been Marshall. When he went to Russia to help the revolution he changed it to Markov. Ganetzski, the minister was also a Jew. When I asked where the Russians were they told me they were back in Russia.

There was a hopeful atmosphere in Riga. The city was crowded with Swedes, Danes and Norwegians who had done business with Russia in pre-war years. They hoped the Soviet monopoly of foreign trade would soon be modified and they could do business again. Large companies had been formed. The Riga customs house and warehouses were filled with goods waiting sale and transshipment to Russia. Most of these goods had to be later sold in Latvia at deflated prices. In a few years all these firms were bankrupt. Not one had succeeded in making steady business with Russia. Most of them had not made any business at all.

Both the American Red Cross and the American Relief Administration (ARA) had large staffs in Riga. There was some rivalry between these organizations. They had divided the relief work. The ARA was busy feeding tens of thousands of children in Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania.

The Red Cross was distributing medicines, equipping hospitals and caring for the health of the inhabitants. The Red Cross men wore uniforms and had been given many decorations. Even the bookkeeper looked like an English general. A fortnight later a telegram came from Moscow announcing my application for a visa had been rejected. It was signed by the chief of the Anglo-American department of the commissariat for foreign affairs who was a Finnish Jew named Nuorteva. I had discovered in New York that Nuorteva had embezzled large sums of money by collecting funds from Jewish clothing merchants for the support of the Soviet representation there and failed to turn this money over to them. One of the members of the Riga staff of the Soviet legation was another New York Jew named Chaiton. I gave him this information about Nuorteva, who a few weeks later was removed from his post and disappeared. Then I made another application. After the usual delay another negative telegram arrived. This time it was signed by Gregory Weinstein who had been one of the office boys in the Soviet legation representation in New York. Incidentally, office boys and messengers in Soviet institutions are all GPU men. I decided to remain in Riga until I could obtain permission to enter Russia.

I waited for this Soviet visa for twenty years, until the Soviet government annexed Latvia and expelled me from the country.

[Page 44]

In February the starving sailors of the Kronstadt garrison revolted. A dramatic battle was fought on the ice of the Neva bay before Petrograd and the Red Army captured the Naval base. The same naval units who had committed so many atrocities during the early years of the revolution and who helped Lenin obtain power were exterminated. A few refugees succeeded in reaching Finland and Estonia over the ice and the first serious uprising against Bolshevism ended in a massacre, setting a precedent which the Soviet regime followed.

Unable to sell confiscated gold abroad, the Soviet government struggled against growing disorganization within Russia. A few weeks later the Red Army succeeded in suppressing another uprising of the Don and Kuban cossacks. At the end of April, the famine, which prevailed in central and northern Russia, extended to the Volga provinces which, next to the Ukraine, are the greatest grain growing regions in Russia. The Soviet government formed a committee of the surviving Russians with internationally known names and published a heartbroken appeal addressed to the world asking to help Russia in her extremity. The Americans responded. Congress appropriated more than sixty-million dollars which was expended for food and medical supplies and saved Bolshevism from collapse.

Maxim Litvinov signed the agreement about the methods and terms of administering American relief in Russia with W.B. Brown of the ARA in Riga. The committee of Russians, the signers of the originaf appeal, disappeared and were not heard of again. The agreement was broken by the Soviet government which forced the ARA to expend large quantities of supplies to feed the personnel of the Soviet railroads and Soviet officials.

One of the conditions of the agreement which was actually fulfilled was the release of five Americans from imprisonment in Russia. I was with the officials who met these men at Narve, an Estonian town on the Soviet frontier. Flick and Estes were motion picture men captured by the Red Army in Russia. Marx was a bearded American of German descent employed as a specialist in Russia. Kalimantiano was an American of Greek descent. The fifth, Pattinger, was a soldier with the Americans troops in Vladivostok who one night boarded a train going in the wrong direction and awoke to find himself a prisoner. All these men were accused of espionage. They had been living in communist prisons from one to three years and were skeletons when they crossed the frontier. All confirmed the stories of mass executions and boundless terror in Russia.

[Page 45]

All reported that the officials of the Cheka, later known as the GPU and NKVD, were Jews. Estes and Flick were dressed in rags. Estes wore a pair of ancient red cavalry pants, faded and discolored. Flick wore a tom jacket and his last pair of pajama pants. All five gained an average of two pounds daily during the first seven days they were at liberty. The stories they told of execution, congested prisons and camps, vermin infested, emaciated prisoners and insufficient quantities of filthy food have since been confirmed by many hundreds of other men of all nationalities who, in one way or another, escaped from degenerate alien controlled Russia. At that time, June 1921, their story was new to a world not yet inured to such horrors.

Although the stories and articles I forwarded to my newspaper the first six months I spent in the Baltic States seemed to preclude my ever obtaining a Soviet visa, I persisted in filing applications regularly every six months for a number of years. In one of the last questionnaires I filled I answered all the questions as foolishly as possible. To the question, who my father was and his occupation, I answered he was a capitalist. To the one asking my reasons for wishing a visa I replied that I desired to enter Russia to collect souvenirs and overthrow the Soviet regime. When this original document arrived in the hands of Gregory Weinstein, chief of the Jewish-Anglo-American affairs commissariat, he became angry and sent a letter to Antonov, the Soviet press chief in Riga, denouncing The Tribune and myself in violent and vulgar language. Antonov foolishly permitted me to copy this letter and I carefully noted the mystical numbers at the top of the letterhead which proved its authenticity beyond doubt. I cabled this document to my paper. It was published, causing a small scandal in Moscow which resulted in Weinstein being transferred to the office of the commissariat of foreign affairs in Leningrad.

This gave me an opportunity I had been awaiting some time. Letting some weeks pass, I wrote Gregory a letter on The Tribune’s letterhead informing him I had made the inquiries he suggested and was sorry to inform him there was no possibility of his obtaining a visa to enter the United States. I further expressed regret at his being to homesick for his many friends in the New York ghetto and suggested, if he was really determined to leave the revolution in the lurch and return to New York then he had better make arrangements to obtain a Canadian visa, reminding him how easy it was to cross the Canadian-American frontier. As I had expected, the letter was immediately sent to the Corohkovaija headquarters of the GPU who placed Weinstein under arrest. He spent several weeks in prison before he was finally released having convinced the authorities it was a hoax. He became a ridiculous figure in Leningrad and was transferred to Ankara. I am not ashamed and have no regrets in playing this trick upon bushy-haired Gregory Weinstein. It was a provocation against a provocateur and it’s too bad it was not still more successful.

[Page 46]

After my incident with Weinstein I seldom visited the Soviet legation in Riga. Therefore I had no opportunities to continue my search for a Soviet foreign official of Russian blood. When M. Chicherin, Soviet foreign commissar, arrived in Rigaenroute to Rapallo, I attended the interview he granted the press in the legation. M. Florinski, his secretary and chief of protocol in the Moscow foreign office, officiated at this ceremony. Both men were Russians. Florinski was. the most effeminate person in male attire I have ever met. with the possible exception of ambassador Bullitt’ s secretary.

Denied the possibility of entering Russia myself, I occasionally employed local journalists to make journeys for The Tribune. I would give these men $500 to cover their expenses, agreeing to pay an additional $23 for each acceptable article they wrote after their return. In this manner we obtained several valuable series of articles revealing the living conditions in Russia. At various times these men visited the Ukraine and Volga districts and one wrote a series of articles about the situation of the orthodox church in Russia.

The Tribune was the only American newspaper or news agency to maintain a staff correspondent north of Berlin. As approximately eighty papers published the news collected by The Tribune’s Foreign Press Service it was largely those uncensored stories about happenings in Russia that stiffened American public opinion against recognition of the Soviet regime. In 1923 when our secretary of state, Charles E. Hughes, sent his polite but caustic note to the Soviet government declining to open diplomatic relations, it was delivered to the Soviet legation in Tallin, Estonia, by the office boy of the American consulate, an unprecedented and calculated insult to the regime of the communist hooligans in Russia.

During the first few years of my reporting news from Riga it was difficult to obtain Soviet newspapers and publications regularly. At that time diplomatic couriers were rapidly acquiring fortunes by smuggling contraband articles to and from Moscow. Officials protected by diplomatic passports also liked to purchase cheap in Moscow and sell dear abroad.

These travelers were the source of much interesting news, and the Latvian censor, with whom I cultivated close relations, kept me supplied with Soviet journals and newspapers until it was possible to formally subscribe to these publications and depend upon their being delivered.

As time passed, Riga became such an important center for Soviet news that Moscow authorities took action. The Soviet foreign office warned travelers against granting interviews in Riga. Later the single sleeping car on the train from Moscow to Riga was disconnected at Dvinski and routed through Lithuania to the German frontier. Travel to Riga was made as inconvenient and uncomfortable as possible. The route over Warsaw was improved and many travelers were given permission to leave Russia only via Poland.

[Page 47]

This action did not destroy Riga’s value as a news center. During this period I was approached on a number of occasions by Soviet officials and offered bribes. As the following letters reveal I kept my editor-in-chief informed as to these developments.

********

The Chicago Tribune Baltic Bureau

Rosenstr. 13/6

Riga, Latvia.

February 24, 1926

Col. R.R. McCormick, Publisher, The Chicago Tribune

Chicago.

Dear Colonel McCormick:

Just recently the Bolsheviks have taken a sudden extraordinary interest in The Chicago Tribune. Mr. Voldemer Anine has arrived here from Moscow and he informs me it is his special mission to find out the sources of all “the incorrect news” which is sent out from Riga. Mr. Anine arranged a meeting with me through some local newspapermen and in the course of our talk I asked him why the Soviets had persistently refused me a visa to enter Russia for the past five years. He said Moscow had very definite information that I was an agent of the American State Department. I naturally denied this allegation and stated I had never accepted money or performed espionage work for any government, let alone our own.

Mr. Anine at a later meeting assured me he was investigating the reports the local Soviet legation had sent about me and would take up with Moscow the matter of granting me a visa. In the meantime, he hinted, I could write my dispatches a little more objectively, for while he admitted the contents of my messages were seldom wrong, still he objected to the way they are written. I informed him the only way they could change my news would be to give me a visa to enter Russia where the censor could control my stories. I said I would continue to write as before.

I reported my first meeting to Steele (our London correspondent) and asked him if I should deny this allegation that I am a spy on our letterhead or should I ask you to deny it. Steele thought this accusation nothing unusual and said he doubted if you would dignify it with a denial, but suggested I report to you. The reason I think it is important is that it might prevent me from entering Russia for some time to come and I am still eager to see the inside of that country.

[Page 48]

From what I have heard there is little doubt but what Anine made the trip to Riga especially to investigate The Tribune. The strength of our news syndicate and the stories I have been writing about, they admit, is delaying the recognition of Russia by the United States. They are now doing everything possible to promote better feelings between the two countries and have even lightened up on the censorship in Moscow as Duranty’s (the correspondent of The New York Times) dispatches show.

According to instructions received some time ago I have made no further applications for a Soviet visa for the past 18 months. When Anine suggested they would be glad to receive another application form I informed him they had some thirty odd applications of mine in Moscow and if they wanted a correspondent at The Tribune to visit Moscow they should invite me. I further said The Tribune was not having a man stationed in Moscow so long as the censorship was maintained over news dispatches, but said you were interested in sending me to Russia to make a trip around the country, investigate conditions and report when I came out.

This is all I have to report on tonight. The economic situation in Russia is again getting interesting and it looks as though the hidden inflation of the Chervonouz will soon begin to show in the interior Soviet bourse. I can also report definitely there will only be a very small export of grain this coming Spring. Saturday I will write a more detailed report on the situation in there.

Many regards to you from, Donald Day, Baltic and Russian Correspondent.

Here is another of the many letters I wrote to Colonel McCormick reporting the intrigues and provocations of the Bolsheviks.

Colonel R.R. McCormick, Publisher.

The Chicago Tribune

Chicago

Dear Colonel McCormick:

Resenstr. l3/8

Riga, Latvia.

9 Sept.1926

I have just had another offer of a Soviet visa, but like previous ones, it had a string attached to it. This time one of the Soviet secretaries phoned and asked me to call. He said Moscow had authorized him to grant me a visa, but on his own responsibility. He said he would not like to take this risk unless I could give guarantee that I would write “objectively” and would not engage in any espionage in Russia. Moscow, he continued, also despite proof of my “loyalnosty” which means loyalty. I informed him that aside from the assurance that I would investigate and write about conditions impartially and I would not do any spying, that I could not give guarantee as far as loyalty went since correspondents were supposed to be loyal to their newspaper above all else. He suggested I think it over and call again.

A few days later I did call to pump out his offer. It developed he wanted me to establish a few agents here, but only in Baltic legations and consulates. My payroll could run as high as SSOO per month and I was to turn over to him all the information I could get about the present negotiations between Russia and the Baltic States regarding separate neutrality pacts. Since these facts are of very little importance I think he figured I could rake down about $400 per month for myself and begin to shade news in their favor. He said after a few months they would give me a visa and even arrange to get me an apartment in Moscow; thus placing me in the same class as commissars. I told him spying was not in my line and left.

The impression I got from these two talks is they want to get me on their payroll so they can feel safe about me before they grant me a visa.

Some one of these days I hope to be invited to Russia to make an investigation of conditions there on our terms. I’ve stuck it out more than five years now and guess I can wait a while longer.

Many regards from, Donald Day, Baltic and Russian Correspondent.

[Page 49]

On another occasion, Umanski, then press chief in the Moscow foreign office and later Soviet ambassador in Washington, was passing through Riga. He invited me to visit him. I refused to call at the Soviet Legation and suggested we meet in a cafe where I naturally brought a friend as a witness. Umanski made me a remarkable offer. First I should send The Tribune only news which would be provided me by the Soviet press attache in Riga. He said this would be a test of “my loyalty towards the Soviet government.” If I consented to do this for three months he would promise me a visa and also an apartment and automobile in Moscow where I could be accepted as the correspondent of The Tribune. As apartments in Moscow are unobtainable except through special assistance of the foreign commissariat this was a considerable bribe. I again declined and reported this offer to my paper.

Later Soviet agents were sent to Riga to deal with me in another fashion. Thanks to the efficiency of the Latvian political police I was unmolested although at different times I was warned against remaining out after dark and was instructed to carry a gun for a short period. My greatest protection was in the fact I represented the largest and most powerful newspaper in the United States which loyally supports its foreign correspondents.

A few years later, when the press chief of the Latvian foreign office, Mr. Alfred Bihlmans, was appointed minister to Moscow, there was a curious development. Bihlmans sent me a pressing invitation to come to Moscow as his guest and he had made arrangements with Soviet foreign so commissariat that I be granted a visa. As Bihlmans wrote, I was not to come to Moscow as correspondent of The Tribune but as a private individual and was not entitled to send any messages while I was there. I was suspicious and delayed my answer by cabling Colonel McCormick the facts asking for his permission. A few days later I received a reply that if I went to Moscow under those conditions it would be at my own risk.

In the meantime, for the first time in my life, I had my fortune told by a gypsy. Mrs. Day and I were walking downtown and I dropped in for a moment to visit my friend Earl Jurgenberg. When I rejoined Mrs. Day on the street she was talking with a gypsy who was trying to persuade her to have her fortune told. I was urged by both and crossing the palm of the gypsy with silver, I turned up my palm. In my pocket I had a book of tickets for the Irish Sweepstakes. I always felt I was going to win a prize for my father had lost so much money at racetracks and in running stables of race horses that I was certain the pendulum would swing back some day and deposit some of this money in my pocket.

The gypsy began to tell me some fact of my early life which happened to be correct and to hasten matters I asked if she saw any money in my hand. This hand spits on money, she exclaimed, spitting herself to illustrate. Money pours through this hand and it will always have money (which was very comforting news to me). She said I was going to receive a letter with money, lots of money, and was going on a journey over the water. This almost convinced me that one of my tickets had already drawn a winning horse for I had planned a trip to America in case fortune rolled my way. I asked if the journey was going to be a long one or a short one and she replied it was very short. I suddenly remembered with sorrow that I had telegraphed The Tribune office in Paris to forward me $500 as I intended to visit Finland and this entailed the very short trip across the water. The gypsy suddenly looked up at me and said earnestly: “Don’t you go in there.” She then passed her fingers across her throat and repeated her warning, pointing with her thumb over her shoulder. This was a real surprise for I had not been thinking of that invitation to visit Moscow. I then urged Mrs. Day to have her fortune told. The old woman took her hand and said immediately:

“This is your second husband and twice in your life you have really wept.”

Other inconsequential things followed. My wife later told me she had wept bitterly on two occasions.

First, when her baby died of starvation in Petrograd during the Bolshevik famine in the winter of 1918-19, and, second, when her husband died during the Bolshevik occupation of Riga. I decided then and there that I would not visit Moscow and before I had rejected the telephone invitation from the Soviet legation to come and get my visa, I had received other warning from more substantial sources.

[Page 51]

Three weeks later Archbishop John Pommers, head of the Orthodox church in Latvia and member of the foreign affairs committee of the Latvian parliament, telephoned. He informed me foreign Minister Zarinsch had just appeared before the committee and read a note from the Soviet Government putting forth three conditions on which Moscow was willing to sign a new trade treaty with Latvia. In 1934 Archbishop John, who was my friend for many years, was murdered in his villa in Meza Parks, a Riga suburb, by Bolshevik agents.

The conditions were: first that 55 White Russians, whose names were mentioned, should be arrested and expelled from the country. Second, the Russian newspaper Sevodnja, published in Riga, should be closed.

Third, that I should be expelled from the country. Archbishop John told me not to be disturbed as the committee had unanimously voted against complying with the Soviet demands. The next morning I visited Minister Zarinsch who confirmed the Archbishop’s information. I asked and received his permission to report this incident to The Tribune.

I shall not claim that Dr. Bihimans was acting in the Soviet government’s interest when he invited me to Moscow as his guest, but in January 1934 I was asked to visit the Latvian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Bihimans had been appointed ambassador to Washington. I was shown a report that Bihimans had written about one of my stories that had appeared in the Tribune on the 1st of January.

In that article I reported that the parliamentary form of government in Latvia had broken down in a jumbled muddle of party politics and corruption, and I predicted that Latvia would presumably be the next country of Europe to have a dictatorial form of government (a result that in fact happened on May 15th of that same year).

Bihimans said that my article was offensive. But since the Tribune supported its correspondents and was the largest and most influential newspaper in America, he suggested that it would be easier to arrange my expulsion from Latvia through harassment. In his report he proposed three methods. First, the Latvian authorities could claim that I had driven my car in the country illegally and could levy so heavy a fine on me that I would be forced to leave. Second, the police could arrest me and accuse me of driving while intoxicated. Third, they could 18 effect a search of my home to look for contraband.

The last suggestion was typical of Bihimans’ character. A few months earlier, shortly before his departure for America, I gave a dinner in his honor and also invited publishers and correspondents from the region. With the dinner I served wine that I had obtained from a foreign consul who had suddenly been transferred, and I told Bihimans that for the first time in my life I had acquired a small wine cellar.*

When I asked the official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the government’s Intentions, he laughed and said;

“Bihimans’ memorandum merely shows that he is still working for the Bolsheviks, and you are welcome to stay in Latvia as long as you wish.”

I would add that during these past twenty-two years I have written many articles that could be considered favorable or unfavorable about all the countries I visited for the Tribune. I never encountered the slightest difficulty with the new directors or other authorities in Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Sweden, Norway, East Prussia, or Danzig, But I had enormous problems with, and probably escaped by good luck the many traps laid by, the authorities in Soviet Russia, Poland, and Lithuania.

I shall explain this briefly. Those three countries were interested in exploiting the United States. They considered that every news bulletin that conflicted with their propaganda in the United States was detrimental to their interests. The Bolsheviks wanted to obtain recognition and credits. The Poles wanted to ship their Jews and other minorities to the United States as immigrants. They also wanted loans and credits, and they further made every effort to increase the money remittances of the 5,000,000 Poles living in America back to Poland. Lithuanian ambitions were precisely the same.

I have written very many articles and forwarded many cables in the course of these years which reflected credit upon Poland and Lithuania. But I also pitilessly exposed those governments when they attempted to exploit my country in favor of their own. It is strange how quickly a favorable article is forgotten and how long an unfavorable one is remembered. The Polish and Lithuanian press chiefs whom I have known seemed to believe that favorable articles were the only kind that should be written by a correspondent.

[* The point here, of course, is that the Jew who had been made Latvian Ambassador to the United States suggested that the Latvian police could find the wine Day had obtained from the consul and, with Jewish ethics, pretend that he had obtained it from smugglers.]

_______________________

NOTES

* Images (maps, photos, etc.) have also been added that were not part of the original Noontide edition.

__________________

Knowledge is Power in Our Struggle for Racial Survival

(Information that should be shared with as many of our people as possible — do your part to counter Jewish control of the mainstream media — pass it on and spread the word) … Val Koinen at KOINEN’S CORNER

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 1: Reviews; Background Information

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 2: Introduction; Permit Me to Introduce Myself

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 3: Why I Did Not Go Home; The U.S.

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 4: Lativa

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 5: Meet the Bolsheviks

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 6: Alliance With the Bear

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 7: Poland

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 8: Trips; The Downfall of Democracy

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 9: Jews

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 10: Russia

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 11: Lithuania

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 12: Danzig; Lithuania

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 13: Sweden; Norway

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 14: Finland

Click to go to >> OCS – Part 15 (last) : England; Europe; Epilogue; Index of Names

PDF of this blog post. Click to view or download (2.0 MB).

>>Onward Christian Soldiers by Donald Day – Part 05

Version History

Version 3: Dec 8, 2019 — Re-uploaded images and PDF for katana17.com/wp/ version

Version 2: Mar 13, 2015 – added image of Libau.

Version 1: Published Mar 13, 2015

Pingback: Onward Christian Soldiers - Part 1: Reviews, Background Information - katana17katana17